1050

Imaging of Irradiation Effects in Brain Tissues by Electrical Conductivity Using MRI

Nitish Katoch1, Bup Kyung Choi1, Ji Ae Park2, Tae Hoon Kim3, Young Hoe Hur4, Jin Woong Kim5, and Hyung Joong Kim1

1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea, Republic of, 2Division of Applied RI, Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Science, Seoul, Korea, Republic of, 3Medical Convergence Research Center, Wonkwang University Hospital, Iksan, Korea, Republic of, 4Department of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreas Surgery, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea, Republic of, 5Department of Radiology, Chosun University Hospital and Chosun University College of Medicine, Gwangju, Korea, Republic of

1Department of Biomedical Engineering, Kyung Hee University, Seoul, Korea, Republic of, 2Division of Applied RI, Korea Institute of Radiological and Medical Science, Seoul, Korea, Republic of, 3Medical Convergence Research Center, Wonkwang University Hospital, Iksan, Korea, Republic of, 4Department of Hepato-Biliary-Pancreas Surgery, Chonnam National University Medical School, Gwangju, Korea, Republic of, 5Department of Radiology, Chosun University Hospital and Chosun University College of Medicine, Gwangju, Korea, Republic of

Synopsis

Keywords: Electromagnetic Tissue Properties, Electromagnetic Tissue Properties, Electrical Conductivity, MREPT, Radiation Therapy, High-field MRI

Radiation-induced injury can damage normal tissues caused by unintentional exposure to ionizing radiation. Image-based evaluation of tissue damage by irradiation has an advantage for the early assessment of therapeutic effects. This study aims to non-invasively evaluate tissue response following radiation therapy in phantoms and in vivo mouse brains at 3T and 9.4T MRI scanner. Due to changes in ionic strength in tissue after radiation, magnetic resonance (MR)-based electrical properties tomography could be a suitable imaging tool to assess the radiation therapy response on biological tissues.Abstract

Ionizing radiation delivers enough energy within the human body to create ions, directly damaging DNA or producing charged particles leading to cell death in cancerous tissues1. Due to changes in ionic strength in tissue after radiation, magnetic resonance (MR)-based electrical properties tomography could be a suitable imaging tool to assess the radiation therapy response on biological tissues2. In this study, we performed MR-based electrical conductivity imaging on designed phantoms to confirm the effect of ionizing radiation at different doses and on in-vivo mouse brains to distinguish tissue response depending on different doses and the elapsed time after irradiation. The conductivity of the phantoms with the distilled water and saline solution increased linearly with the irradiation doses. The measured absolute conductivity of in vivo mouse brains showed different time-course variations and residual contrast depending on the irradiation doses.Methods

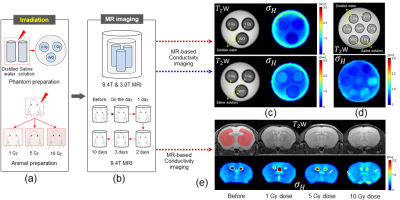

Two phantoms were prepared using distilled water and saline solution, respectively. Three small cylindrical tanks containing distilled water and saline solution, consisting of without and with irradiation of 1 Gy & 2 Gy doses, were placed inside the cylindrical phantom 30 mins after of irradiation. Neutron beam including fast neutrons was produced by irradiating a proton beam (20 μA, 35 MeV) on a beryllium target using a KIRAMS MC-50 cyclotron3.Nine female 6-week-old BALB/c nude mice (weighing 20~23 g) were used. The mice were divided into 3 groups: 1 Gy, 5 Gy, and 10 Gy irradiation doses. All mice were subjected to imaging before and at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 10 days after irradiation (Fig. 1b). Mice were irradiated with a 1 Gy, 5 Gy, and 10 Gy dose, respectively, using a small animal image-guided irradiation system X-RAD SmART (Precision Inc., USA) as shown in fig 1a3.

MR and electrical conductivity images of phantoms were obtained at 3T (Magnetom Trio A Tim, Siemens Medical Solutions) and a 9.4T MRI scanner (Agilent Technologies). For T2W, a fast spin-echo multi-slice (FSE-MS) MR sequence was applied, and the imaging parameters: TR=3500 ms, TE=30ms, ETL=6, NEX=2, slice thickness=1 mm, slices=5, matrix size=128×128, FOV=50×50 mm2, Scan time=2 min 48 sec. For the electrical conductivity imaging, a multi-echo multi-slice (MEMS) spin-echo MR sequence was applied to obtain the B1 maps, which are used to recover high-frequency isotropic conductivity images4. Imaging parameters: TR=2200 ms, TE=22 to 132 ms, NE=6, NEX=5, slice thickness=1 mm, number of slices 5, matrix size=128×128, FOV=50×50 mm2, total imaging time of about 23 min 46 sec.

Results and Discussion

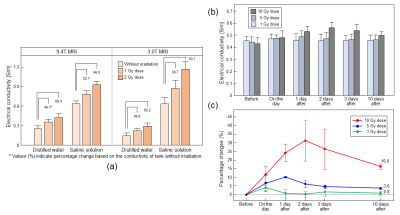

Fig. 1 shows the experiment design, T2W, and electrical conductivity images of the phantoms and mouse brains according to different irradiation doses. The phantoms using distilled water and saline solution were imaged separately in 9.4T MRI (Fig. 1c), but combined in 3.0T MRI (Figure 1(d)). Fig. 1e shows MR and electrical conductivity images of in vivo mouse brains before and after irradiation with different doses. No morphological differences without and with irradiation of 1 Gy and 2 Gy doses were not observed in the T2W. The measured conductivity of the saline solution was higher than that of the distilled water in both magnetic field strengths. Conductivity values in saline solution range from 0.63 to 1.17 S/m, and in distilled water range from 0.21 to 0.42 S/m. The irradiation dose linearly changed the overall relative conductivity changes of the distilled water and saline solution at both field strengths. The relative conductivity changes in distilled water range from 40.7 to 69.4%, whereas in saline solution, the relative change ranges from 22.7 to 46% (Fig. 2a). The higher conductivity in the saline solution could stem from higher concentrations of composing ions than those in distilled water. Fig. 1e shows the T2W and electrical conductivity images of in vivo mouse brains according to different irradiation doses after day 1. Fig. 2b&c show the conductivity measured and relative change on different time points from ROI shown in fig. 1e. Fig. 2b shows the relative conductivity change representing the sensitivity of the irradiation effects on brain tissues based on the values found before irradiation. The conductivity changes at the 10 Gy dose were the largest at all measurement times, and measured conductivity ranges from 0.45 to 0.60 S/m. We also analyzed the relative change in conductivity with different doses and course of time (Fig. 2c). The sensitivity of the 10 Gy dose increased by 30% up to 2 days after irradiation and then decreased. The 5 Gy dose increased by 10% up to 1 day after irradiation and then decreased. There was no clear change in the 1 Gy dose. Over time, electrical conductivity shows contrast changes with different doses and elapsed times after irradiation, whereas no significant morphological changes were observed. This may stem from the fact that cell functions are damaged by irradiation, and the ionic concentration changes because of the accumulated irradiation. This situation, such as the changes in concentration of ions, can impact electrical conductivity2,4.Conclusion

In this study, we applied MR-based electrical properties tomography technique to image the irradiation effects. The electrical conductivity of two phantoms and mouse brains after irradiation shows a linear change in conductivity and radiation dose. MREPT shows potential as tool to monitor the therapeutic effect of radiation.Acknowledgements

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grants funded by the Korea government (No. 2019R1A2C2088573, 2020R1I1A3065215, 2020R1A2C200790611, 2021R1I1A3050277, 2020R1I1A1A01073871, 2021R1A2C2004299, 2022R1I1A1A01065565).References

1. Miller, Joseph P., et al. Clinical doses of radiation reduce collagen matrix stiffness. APL bioengineering 2.3 (2018): 031901.2. Park, Ji Ae, et al. In vivo measurement of brain tissue response after irradiation: comparison of T2 relaxation, apparent diffusion coefficient, and electrical conductivity. IEEE transactions on medical imaging 2019; 38:2779-2784.

3. Yang, Miyoung, et al. Fast neutron irradiation deteriorates hippocampus-related memory ability in adult mice. Journal of veterinary science 2012:13:1 1-6.

4. Katscher, U et al. Magnetic Resonance Electrical Properties Tomography (MREPT). “Electrical Properties of Tissues”. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 2022, vol. 1380. Springer.

Figures

Fig. 1: Schematic illustration of experimental setup for MR-based electrical conductivity imaging for measuring the irradiation effects phantoms (a) and in vivo mouse brains (b). T2-weighted and electrical conductivity images of phantom with the distilled water and saline solution at 9.4T MRI (c), at the clinical 3T MRI system (d). T2-weighted MR and electrical conductivity images of the mouse brain represent the time-course variations in contrast related to its tissue response following external irradiation (e).

Fig. 2: (a)

Bar plot of relative conductivity changes in phantoms obtained from 3T and 9.4T

MRI by different irradiation doses. Quantitative analysis of in vivo

brain (b) Absolute conductivity from ROI shown in Fig. 1e and relative

conductivity change (c) from doses of 1, 5, and 10 Gy.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1050