1038

Circadian influence on brain connectivity revealed by resting-state fMRI in awake mice1Advanced Imaging Research Center, University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, fMRI (resting state), Circadian rhythm

Circadian rhythms control almost all our vital physiology and cognitive functions. Disruptions of circadian rhythms are also reported in multiple neuropsychiatric disorders. However, the neural network-level study of the circadian system in vivo has been understudied. Here we use awake mice resting-state fMRI to characterize the functional connectivity changes at different time points in the circadian cycle. Our results indicate that circadian oscillations can alter the functional connectivity across the brain with various changes depending on the local circuits. Particularly, the midbrain dopaminergic system showed a trend of stronger connectivity to the cortex at night compared to the morning.Introduction

Circadian rhythms synchronize biological processes on a 24-hour periodic cycle. Almost all our vital functions are controlled by circadian oscillations. Multiple brain regions, such as the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), striatum, forebrain, and thalamus, have been discovered to produce 24-hour rhythms in the expression of core clock genes [1,2]. However, the neural network-level study of the circadian system in vivo has rarely been investigated. Recent studies have shown a daily rhythm of midbrain dopamine release [3]. Anatomically, the highly synchronized SCN neurons project to a broad range of structures in the brain [4]. Therefore, we hypothesize that the brain-wide functional connectivity alters due to the effect of circadian oscillations. Here we acquire resting-state fMRI data on awake mice at different time points in the circadian cycle. The awake mice setup is aimed at avoiding physiological confounds from conventional anesthesia preparation in small animal studies [5]. We expect our results to provide insights into circadian impacts on whole-brain functional connectivity, especially the midbrain dopaminergic system.Methods

All animal experiments follow the protocol approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC). Adult male C57BL/6J mice, under an LD12:12 light-dark cycle with head-bar implantation, were acclimated to the MRI environment. MRI acquisition: MRI data were acquired using a 7T MRI scanner at two-time points in the morning (9-10 am) and night (9-10 pm) of four different days, respectively. Gradient echo EPI sequence was implemented with TR/TE = 2000/20 ms; in-plane resolution = 200 × 200 um; matrix size = 96 × 72; slice thickness = 1 mm; FOV = 19.2 mm × 14.4 mm; scan time = 10 minutes x 3 sessions. Turbo RARE was used for anatomical imaging. Image analysis: Standard fMRI preprocessing pipeline was followed using AFNI and MATLAB programs [6]. All the EPI images were registered to the Paxinos mouse brain atlas and bandpass filtered (0.01 Hz – 0.1 Hz) [7]. Seed analysis was conducted based on thirteen regions - substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc), ventral tegmental area (VTA), lateral hypothalamus (LH), dorsal striatum (DS), ventral striatum (VS), paraventricular thalamic nucleus (PVT), ventral paraventricular hypothalamic nucleus (PaV), retrosplenial cortex (RSC), cingular cortex (CC), superior colliculus (SC), primary visual cortex (VC), primary somatosensory barrel cortex (S1BF), and motor cortex (MC). For seed analysis, MATLAB-based custom-written script was used. For group analysis, data obtained from four days were concatenated.Results

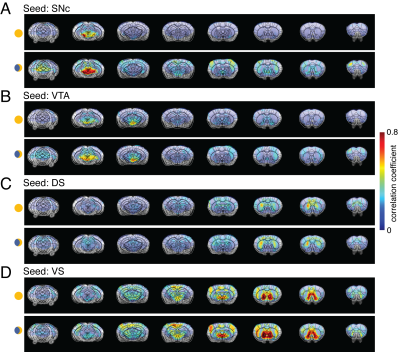

Four ROIs from the midbrain dopaminergic system, SNc, VTA, DS, and VS, were selected for seed-based whole-brain functional connectivity analysis. Figure 1 compares the correlation maps between morning and night based on different ROI seeds. Interestingly, multiple brain areas show increased functional connectivity to SNc at night compared to the morning (Fig1. A), including dorsal and ventral striatum, thalamus, and broad cortical regions. In contrast, the correlation maps of VTA show increased connectivity at night, mainly in the sensory cortex and superior colliculus (SC) (Fig1.B). DS and VS connectivity results show fewer changes. Increased connectivity around the motor cortex (MC) and somatosensory cortex were observed from DS correlation maps at night (Fig1.C). VS offers robust connectivity to multiple brain areas both at night and in the morning (Fig1.D). The correlation strength increased in the visual cortex (VC) and whisker barrel cortex (S1BF). To quantitatively explore the whole-brain connectivity changes between day and night, we then performed ROI-based cross-correlation analysis (Fig2.) Nine more ROIs were selected, including thalamus subregions – PVT, SC, hypothalamus areas – LH and PaV, and the cortex – RSC, CC, VC, S1BF, and MC. Both PVT and PaV are known to receive intensive neuronal inputs directly from the brain clock center SCN. Interesting trends of connectivity changes were observed when subtracting the morning cross-correlation matrix from the night matrix. The connectivity strength between the selected cortical and subcortical regions is generally increased at night at different levels. In the color-coded connectivity change map (Fig2.C), redder indicates a higher increase at night. We performed group statistic tests on the ROI cross-correlation results to further quantify the findings. The connectivity between two pairs of ROIs was found significantly increased at night: PaV vs. VC and SNc vs. S1BF (Student‘s t-test, n = 4, p < 0.05). These results indicate that circadian oscillations can alter the functional connectivity across the brain with various changes depending on the local circuits.Conclusion and Discussion

Using resting-state fMRI on awake head-restrained mice, we demonstrated whole-brain functional connectivity in the morning and night. Our results indicate that circadian oscillations alter functional connectivity across the brain. The significantly stronger connectivity between PaV and VC at night indicates the impact of the circadian rhythm on the neuronal activity at the hypothalamus and the optical processing system, which is consistent with the earlier reports that calcium activity in SCN, the primary input source of PaV, oscillates during the day and night [8]. In contrast, the significant connectivity between SNc and S1BF, and the increasing connectivity trend between VTA and S1BF are new findings in this study. We expect our follow-up study with more animals and more imaging time points in the circadian cycle will bring further insights into how circadian oscillations impact the dopaminergic system and its connectivity to the rest of the brain.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Endowed Scholar Program of UT Southwestern Medical Center, UT System Rising STARs Award, and the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) grant of the Advanced Imaging Research Center at UT Southwestern Medical Center (RP210099).References

1. Colwell, C.S. Linking neural activity and

molecular oscillations in the SCN. Nat Rev Neurosci 12, 553-569 (2011).

2. Begemann, K., Neumann, A.M. & Oster, H.

Regulation and function of extra-SCN circadian oscillators in the brain. Acta

Physiol (Oxf) 229, e13446 (2020).

3. Chung, S., et al. Impact of circadian nuclear receptor REV-ERBalpha on midbrain dopamine production and mood regulation. Cell 157, 858-868 (2014).

4. Becker-Krail, D.D., Walker, W.H., 2nd & Nelson, R.J. The Ventral Tegmental Area and Nucleus Accumbens as Circadian Oscillators: Implications for Drug Abuse and Substance Use Disorders. Front Physiol 13, 886704 (2022).

5. Jordan, D., et al. Simultaneous electroencephalographic and functional magnetic resonance imaging indicate impaired cortical top-down processing in association with anesthetic-induced unconsciousness. Anesthesiology 119: 1031–1042, (2013).

6. Cox, R. W. “AFNI: Software for Analysis and Visualization of Functional Magnetic Resonance Neuroimages,” Computers and Biomedical Research, vol. 29, no. 3, pp. 162–173 (1996).

7. Paxinos, G. and Watson, C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates (1982).

8. Colwell, C. Circadian modulation of calcium levels in cells in the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 571–576 (2000).

Figures