1036

Optogenetic modulation of the mouse default mode network with a single tapered fiber

Elizabeth de Guzman1, Barbara Spagnolo2, Filippo Pisano2, Marco Pisanello2, Alberto Galbusera1, Luigi Balasco3, Yuri Bozzi3, Massimo De Vittorio2,4, Tommaso Fellin5, Ferruccio Pisanello2, and Alessandro Gozzi1

1Functional Neuroimaging Lab, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Rovereto, Italy, 2Center for Biomolecular Nanotechnologies, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Arnesano (Lecce), Italy, 3Center for Mind/Brain Sciences (CiMEC), University of Trento, Rovereto, Italy, 4Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’Innovazione, Università del Salento, Lecce, Italy, 5Optical Approaches to Brain Function Laboratory, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Genova, Italy

1Functional Neuroimaging Lab, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Rovereto, Italy, 2Center for Biomolecular Nanotechnologies, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Arnesano (Lecce), Italy, 3Center for Mind/Brain Sciences (CiMEC), University of Trento, Rovereto, Italy, 4Dipartimento di Ingegneria dell’Innovazione, Università del Salento, Lecce, Italy, 5Optical Approaches to Brain Function Laboratory, Istituto Italiano di Tecnologia, Genova, Italy

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, fMRI, preclinical, functional connectivity, neural oscillations, DMN

The default mode network (DMN) is a distributed functional system of the human brain widely studied with fMRI due to its involvement in advanced cognitive processes and its dysregulation in a variety of brain disorders. Causal perturbations of this network in physiologically accessible species are critically required to probe its circuit organization and the underpinnings of its (dys)function. Here we show that tapered fiber optogenetic technology enables the reliable stimulation of key DMN nodes in a frequency dependent fashion, overcoming the limitations of traditional optogenetic approaches.Introduction

Resting state fMRI (rsfMRI) is used to explore the intrinsic network organization of the human brain in the absence of explicit tasks. Spontaneous low-frequency oscillations in BOLD fMRI signal exhibit reproducible and anatomically specific patterns of correlations between different brain areas, defining large-scale, anatomically distributed functional connectivity (FC) networks. A widely investigated FC network of the human brain is the default mode network (DMN), a system thought to be a key substrate of internal modes of cognition such as empathy, recollection and imagination, conceptual processing and conscious awareness1. The robust evidence for altered DMN connectivity under pathological states1 has spurred research into the presence of anatomically conserved DMN precursors in accessible species. Recent years has witnessed the discovery of an analogous rodent DMN system involving evolutionarily conserved associative prefrontal and peri-hippocampal cortices2. Cell-type specific neural perturbation of the DMN in rodents offers the opportunity to investigate the core constituents and neurobiological underpinnings of DMN (dys)function. However, the widely distributed topography and associative nature of the DMN pose challenges for opotgenetic stimulation. Traditional flat fiber technology is typically limited to focal manipulation of individual circuit components due to the risk of tissue heating and spurious hemodynamic responses3. To attain homogeneous photostimulation of large volumes and network-scale manipulations of the DMN, we propose the combined use of mouse fMRI and tapered fiber (TF) technology4. Here, we describe and thoroughly validate the use of TF technology to attain network level manipulations of the DMN through photostimulation of the mouse medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), one of its evolutionarily-conserved core constituents5.Methods

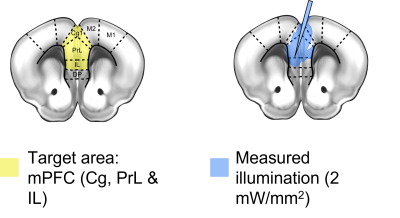

For validation of the TF system, Thy1-ChR2 mice (B6.Cg-Tg(Thy1-COP4/EYFP)18Gfng/J; Jax #7612; expressing channelrhodopsin-2 [ChR2] under the Thy1 promoter) were used. Proof-of-concept experiments exploring the impact of different stimulation parameters were instead performed in mice injected with a viral vector expressing ChR2 under the CamkIIα promoter (AAV5-CamkIIα-hChR2(H134R)-EYFP, Addgene #26969). The single TF was implanted in the mPFC at a 15o angle (AP +1.9 mm; ML +/- 0.6mm; DV –2.1 mm; Figure 1). Blood oxygen level dependent (BOLD) images were acquired on a 7T scanner (Bruker) using an echo planar imaging gradient echo (EPI-GE) sequence with the following parameters: TE=15ms, TR=1s, flip angle=60o, NR=390, matrix size=98x98, slice number=18, field of view=2.3x2.3x9.9mm. All scans were acquired under anesthetic; a combination of medetomidine (0.1 mg/kg/h i.a) and isoflurane (0.5%) (med-iso) was used for the majority of experiments. Photostimulation was performed by pulsing light either in a block design (15ms pulses at a frequency of 20Hz for 10s, every 60s) or continuously. BOLD images were reconstructed and preprocessed as previously described6. The evoked response from block design stimulation was characterized with a GLMM7, and by modelling the hemodynamic response function as a Fourier basis set convolved with a boxcar function representing the stimulation paradigm. FC differences due to continuous stimulation were evaluated compared to opsin free controls.Results and discussion

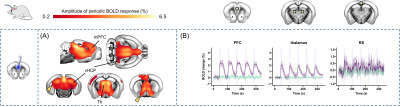

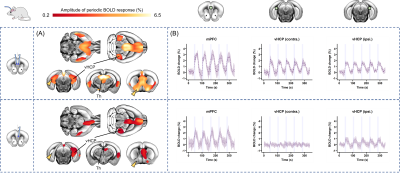

Single probe dual hemisphere illumination was achieved by implanting a single TF into the mPFC at a 15o angle, crossing the midline such that light was delivered on both sides. The success of this method was demonstrated in slice by light emission induced fluorescence from a tapered fiber implanted into a coronal section from a Thy-ChR2 mouse (Fig. 1). In keeping with this, in vivo optogenetic-fMRI studies revealed that stimulation of pyramidal cells with a single TF in the mPFC under either promoter (Thy1: Fig. 2; CamkIIα: not shown) resulted in exquisitely bilateral stimulation of key DMN afferents. The largest response was detected in the thalamus, a region recently recognized as an important component of the DMN. Notably, the bilateral response achieved with a single low-invasive TF was comparable to that obtained with a canonical dual flat fiber configuration, and distinct from the unilateral response obtained with a single flat fiber implant (Fig. 3). We also tested for possible heat or visual induced responses by implanting control mice (without ChR2) with a TF. Contrary to previous observations with flat fibers3,8, we found that TFs could be used to perform widespread illumination without any observable changes in BOLD response (Fig. 2, green/dashed line). Similarly corroborating the specificity of the mapped effects, blood pressure recordings obtained during stimulation under different anesthetics (med-iso vs. halothane) showed that the evoked response was uncoupled from peripheral cardiovascular changes. Finally, proof-of-concept experiments were performed using this technology, showing that continuous rhythmic stimulation of the mPFC resulted in changes to the FC of cortical and subcortical DMN substrates that were dependent on the stimulation frequency. Importantly, while the evoked response from block stimulation could be predicted from mPFC projections, continuous stimulation engaged components of the DMN above and beyond what would be expected from the structural connectome9.Conclusions

We show that it is possible to use a single tapered fiber to reliably photostimulate the mouse mPFC and bilaterally engage synchronous activity within anatomical nodes of the DMN as predicted by the distributed wiring diagram of this region5. Importantly, proof-of-concept studies showed that anatomical substrates engaged by continuous or rhythmic mPFC stimulation are anatomically and functionally different, hence paving the way to the investigation of the dynamic rules governing the organization of this translationally relevant network.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the European Research Council (ERC – DISCONN; no. 802371 to A.G.)References

- R.L. Buckner et al. “The brain's default network: anatomy, function, and relevance to disease,” Ann N Y Acad Sci. Vol. 1124, pp.1-38. Mar. 2008

- F. Sforazzini et al. “Distributed BOLD and CBV-Weighted Resting-State Networks in the Mouse Brain.” NeuroImage Vol. 87: pp. 403–15. 2014.

- I. N. Christie et al., “FMRI response to blue light delivery in the naïve brain: Implications for combined optogenetic fMRI studies,” Neuroimage, vol. 66, pp. 634–641, 2013.

- F. Pisanello et al., “Dynamic illumination of spatially restricted or large brain volumes via a single tapered optical fiber.,” Nat. Neurosci., vol. 20, no. 8, pp. 1180–1188, Aug. 2017.

- J. Whitesell et al. “Regional, Layer, and Cell-Class Specific Connectivity of the Mouse Default Mode Network.” Neuron, 2020

- F. Sforazzini, A. J. Schwarz, A. Galbusera, A. Bifone, and A. Gozzi "Distributed BOLD and CBV-weighted resting-state networks in the mouse brain". NeuroImage, 2014

- D. Bates, M. Mächler, B. Bolker, and S. Walker, “Fitting Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using lme4,” J. Stat. Softw., vol. 67, no. 1, 2015.

- F. Schmid et al. “True and Apparent Optogenetic BOLD FMRI Signals.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 77, pp.126-136, 2017.

- L. Colettaat al. "Network structure of the mouse brain connectome with voxel resolution." Science Advances, 6(51),2020

Figures

Fig. 1: Implant schematic and

emission properties. (A) A single tapered fiber [TF] was inserted at an angle in order to target the mouse medial prefrontal cortex [mPFC, yellow]. (B) Since light is emitted along the

length of the TF, illumination of both hemispheres of the mPFC is achieved, as

demonstrated by the illumination area.

Fig. 2: Network-level stimulation of the DMN with a single TF. Using a single TF, optogenetic

stimulation of the mPFC in Thy1-ChR2 mice evoked a bilateral increase in BOLD signal throughout the brain, including the thalamus [Th] and ventral hippocampus [vHCP] (A, regions with significant response compared to opsin-free controls shown with colour map). This response (B, purple) was timed to the

optical stimulation [5 blocks at 10s on/50s off]. In illuminated, but opsin-free control mice (B, green) there was no response.

Fig. 3: Similar to the response from a single TF, the evoked BOLD response

from dual flat-fiber [FF] stimulation (top) was bilateral and distinct from unilateral FF (bottom)

stimulation. On the colour map showing regions with significant increases in BOLD signal (A), yellow arrows point to the contralateral vHCP and basal forebrain. Despite successfully stimulating the mPFC (B), there is no response in these contralateral regions from unilateral FF stimulation. In contrast, dual-FF and single-TF stimulation (Fig. 2, yellow arrows) both produce bilateral increases in BOLD signal.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1036