1034

Gaining insight into the neural basis of resting-state fMRI signal1Department of Biomedical Engineering, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, United States, 2National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health, Baltimore, MD, United States, 3The Huck Institutes of the Life Sciences, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Multimodal, fMRI (resting state), Awake, Calcium fiber photometry, BOLD

Understanding the relationships between neuronal, vascular and Blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signals is essential for the appropriate interpretation of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) results in relation to the corresponding neuronal activity. In this study, we utilized multimodal imaging technique that concurrently measures BOLD fMRI and calcium-based fiber photometry signal to examine the relationship between BOLD and neural spiking activity in awake rats. Our results demonstrated significant correspondence between the BOLD and calcium signals at both evoked and resting state, suggesting critical role of spiking activity in the neural mechanism underlying BOLD signal.Introduction

Blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD) signal is generally believed to be coupled with neural activity through neurovascular coupling1,2. However, the exact relationship between BOLD and its underlying neural activity during resting state is still elusive. Recent advances in genetically-encoded calcium indicators allowed the measurement of neural activity3-11 through calcium-dependent fluorescence signal. Unlike electrophysiology, calcium-based measurement using fiber photometry is insensitive to electromagnetic interference12,13 when measured concurrently with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which is particularly important when studying spontaneous neural activity. However, previous studies were predominantly conducted in anesthetized animals. Anesthesia may profoundly alter neuronal and vascular activities14-16, and have significant impact on neurovascular coupling. To bridge this gap, we simultaneously collected fMRI and calcium signal in awake rats to investigate the coupling relationship between the BOLD signal and spiking activity at both evoked and resting state.Methods

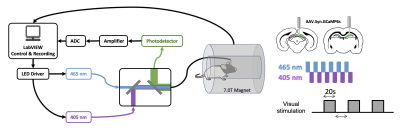

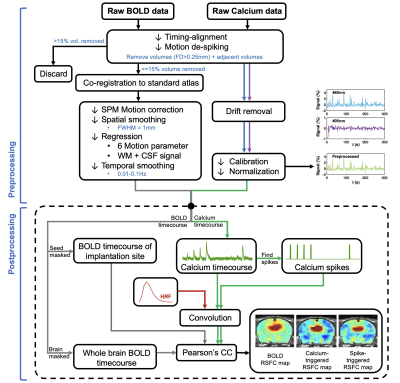

AAV5/9.Syn.GCaMP6s virus was injected into either in dorsal hippocampus (dHP, n=16) or superior colliculus (SC, n=7) in male Long Evans rats. A fiber optic cannula (400 μm core, NA=0.50) was implanted above injection site. Rats were acclimated to a mock scanning environment for 7 days to minimize motion and stress14,17. All fMRI experiments were conducted on a 7T Bruker scanner (Figure 1). T2*-weighted rsfMRI images were collected with the following parameters: TR=1s, TE=15ms, FOV=3.2 × 3.2 cm2; matrix size=64 × 64, slice number=20, slice thickness=1 mm, 600 volume each scan. In tasked sessions, visual stimulation was presented to the rat’s left eye using a 20s-light ON/20s-light OFF paradigm. Calcium signals were simultaneously collected with fMRI using a dual-wavelength fiber-photometry system18. Ca2+-dependent (465 nm) and Ca2+-independent (405 nm) LED light modulated at 400 Hz (40% duty cycle) were delivered to the implanted fiber through a patchcord (400 μm core, NA=0.48, 7 m long). The emitted fluorescent signal was amplified, bandpass filtered (0.3-1 kHz) and recorded (10k Hz sampling rate).The fMRI and calcium photometry data were first temporally aligned (Figure 2). A python-based pipeline was used for calcium signal preprocessing19. A MATLAB-based pipeline was used for fMRI data preprocessing20-23. The calcium-predicted BOLD signal was generated by convolving the calcium signal with a hemodynamic response function (HRF) characteristic to rats10. More details of methods can be found in our publication24.

Results

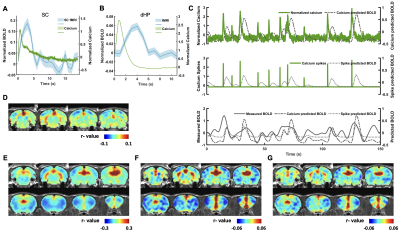

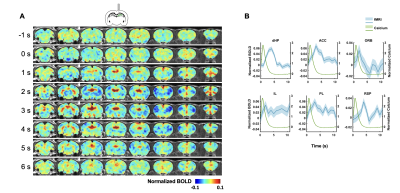

In this study, we examined the coupling between the BOLD signal and neural spiking activity in awake rats at both evoked and resting state. We observed a robust visual evoked increase in calcium signal in the SC (Figure 3A). The calcium-derived BOLD map demonstrated a region-specific correspondence between calcium-derived and measured BOLD signal (Figure 3D). These confirm the validity of this platform in awake rats.We then examined the coupling of BOLD and calcium signal at resting state. We observed a clear correspondence between the measured BOLD, spontaneous calcium- and calcium spike-predicted BOLD signals in the dHP (Figure 3B&C). We also found a high consistency in the spatial patterns of dHP functional connectivity (FC) maps between BOLD-derived, calcium signal-triggered and spike-event triggered maps (Figure 3E-G). To assess their spatiotemporal relationship, we plotted the averaged BOLD signals after detected calcium spikes in the dHP in various brain regions (Figure 4). Multiple brain regions, including default mode network (DMN) regions, exhibited clear and significant changes in BOLD signal after calcium peaks detected in dHP. Taken together, these results suggest a strong coupling between calcium signal in one region and BOLD signal in distributed regions within a functional network.

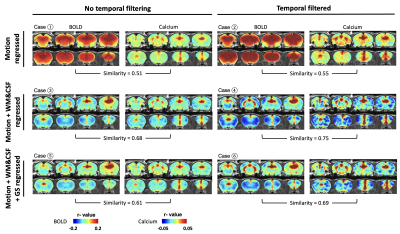

We next assessed the efficacy of different preprocessing steps on rsfMRI data. Our calcium-derived seed maps demonstrated high consistency across different steps (Figure 5), suggesting that calcium signal was insensitive to non-neural artifacts and can provide reliable measurements of neuronal activity. In contrast, BOLD-derived seed maps were highly sensitive to different processing steps. White matter/cerebrospinal fluid (WM/CSF) and/or global signal regression significantly improved the spatial specificity in BOLD-derived seed maps. Temporal filtering (TF) did not affect the spatial specificity but increased contrast-noise ratio. By comparing spatial similarity, Case 4 (motion, WM&CSF regression + TF) provides more optimal performance to rsfMRI data preprocessing.

Discussion

In this study, we established a platform for simultaneous fMRI and dual-wavelength GCaMP-based fiber photometry measurements in awake rodents. Our platform avoids the potential confounding factor of anesthesia, which may affect the interpretation of relationship between neurovascular coupling and brain functional imaging signal6,25. We demonstrated significant correspondence between calcium activity and BOLD signal at both evoked and resting states, which are consistent with previous reports in cortical regions5,7,9,11,12. In contrast, weak coupling between resting-state BOLD and calcium signal was observed in subcortical regions such as SC and lateral geniculate nucleus10. This discrepancy may result from higher baseline firing rate in the dHP and cortex, or different anesthetic conditions under which signals were acquired. We also demonstrated prominent spatiotemporal coactivation patterns after dHP calcium spikes in spatially distant regions. These coactivated regions colocalize with the DMN, which has been found to exist in multiple species26-30. Furthermore, regression of WM/CSF and/or GS improved spatial specificity of BOLD-derived seed maps, suggesting the critical role of nuisance signal regression in rsfMRI preprocessing pipelines. Taken together, our results suggest critical role of spiking activity in neural mechanism underlying the BOLD signal.Acknowledgements

The present study was partially supported by National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R01NS085200), National Institute of Mental Health(RF1MH114224), and National Institute of General Medical Sciences(R01GM141792). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.References

1. Hillman, E. M. Coupling mechanism and significance of the BOLD signal: a status report. Annual review of neuroscience 37, 161 (2014).

2. Kim, S.-G. & Ogawa, S. Biophysical and physiological origins of blood oxygenation level-dependent fMRI signals. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 32, 1188-1206 (2012).

3. Chen, X. et al. Mapping optogenetically-driven single-vessel fMRI with concurrent neuronal calcium recordings in the rat hippocampus. Nature communications 10, 1-12 (2019).

4. He, Y. et al. Ultra-slow single-vessel BOLD and CBV-based fMRI spatiotemporal dynamics and their correlation with neuronal intracellular calcium signals. Neuron 97, 925-939. e925 (2018).

5. Lake, E. M. et al. Simultaneous cortex-wide fluorescence Ca2+ imaging and whole-brain fMRI. Nature methods 17, 1262-1271 (2020).

6. Liang, Z., Ma, Y., Watson, G. D. & Zhang, N. Simultaneous GCaMP6-based fiber photometry and fMRI in rats. Journal of neuroscience methods 289, 31-38 (2017).

7. Pais-Roldán, P. et al. Indexing brain state-dependent pupil dynamics with simultaneous fMRI and optical fiber calcium recording. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 117, 6875-6882 (2020).

8. Schulz, K. et al. Simultaneous BOLD fMRI and fiber-optic calcium recording in rat neocortex. Nature methods9, 597-602 (2012).

9. Schwalm, M. et al. Cortex-wide BOLD fMRI activity reflects locally-recorded slow oscillation-associated calcium waves. Elife 6, e27602 (2017).

10. Tong, C. et al. Differential coupling between subcortical calcium and BOLD signals during evoked and resting state through simultaneous calcium fiber photometry and fMRI. Neuroimage 200, 405-413 (2019).

11. Wang, M., He, Y., Sejnowski, T. J. & Yu, X. Brain-state dependent astrocytic Ca2+ signals are coupled to both positive and negative BOLD-fMRI signals. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 115, E1647-E1656 (2018).

12. Schlegel, F. et al. Fiber-optic implant for simultaneous fluorescence-based calcium recordings and BOLD fMRI in mice. Nature protocols 13, 840-855 (2018).

13. Carmichael, D. W. et al. Simultaneous intracranial EEG–fMRI in humans: protocol considerations and data quality. Neuroimage 63, 301-309 (2012).

14. Gao, Y.-R. et al. Time to wake up: Studying neurovascular coupling and brain-wide circuit function in the un-anesthetized animal. Neuroimage 153, 382-398 (2017).

15. Hamilton, C., Ma, Y. & Zhang, N. Global reduction of information exchange during anesthetic-induced unconsciousness. Brain Structure and Function 222, 3205-3216 (2017).

16. Paasonen, J. et al. Multi-band SWIFT enables quiet and artefact-free EEG-fMRI and awake fMRI studies in rat. NeuroImage 206, 116338 (2020).

17. Dopfel, D. & Zhang, N. Mapping stress networks using functional magnetic resonance imaging in awake animals. Neurobiology of stress 9, 251-263 (2018).

18. Kim, C. K. et al. Simultaneous fast measurement of circuit dynamics at multiple sites across the mammalian brain. Nature methods 13, 325-328 (2016).

19. Martianova, E., Aronson, S. & Proulx, C. D. Multi-fiber photometry to record neural activity in freely-moving animals. JoVE (Journal of Visualized Experiments), e60278 (2019).

20. Liang, Z., King, J. & Zhang, N. Anticorrelated resting-state functional connectivity in awake rat brain. Neuroimage 59, 1190-1199 (2012).

21. Liang, Z., Li, T., King, J. & Zhang, N. Mapping thalamocortical networks in rat brain using resting-state functional connectivity. Neuroimage 83, 237-244 (2013).

22. Liu, Y. et al. An open database of resting-state fMRI in awake rats. NeuroImage 220, 117094 (2020).

23. Ma, Z. et al. Functional atlas of the awake rat brain: A neuroimaging study of rat brain specialization and integration. Neuroimage 170, 95-112 (2018).

24. Ma, Z., Zhang, Q., Tu, W. & Zhang, N. Gaining insight into the neural basis of resting-state fMRI signal. Neuroimage 250, 118960 (2022).

25. Ma, Y., Ma, Z., Liang, Z., Neuberger, T. & Zhang, N. Global brain signal in awake rats. Brain Structure and Function 225, 227-240 (2020).

26. Vincent, J. L. et al. Intrinsic functional architecture in the anaesthetized monkey brain. Nature 447, 83-86 (2007).

27. Rilling, J. K. et al. A comparison of resting-state brain activity in humans and chimpanzees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 104, 17146-17151 (2007).

28. Stafford, J. M. et al. Large-scale topology and the default mode network in the mouse connectome. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 111, 18745-18750 (2014).

29. Lu, H. et al. Rat brains also have a default mode network. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences109, 3979-3984 (2012).

30. Ma, Z., Ma, Y. & Zhang, N. Development of brain-wide connectivity architecture in awake rats. Neuroimage176, 380-389 (2018).

Figures