1029

Individualized representation learning of resting-state fMRI1University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, fMRI (resting state)

We describe a generalizable, modular and explainable model for individualized representation learning of resting-state fMRI. The model consists of a “deep” base which learns representations that are unique to each individual brain through self-supervised learning, and “shallow” adds-on which are trained with supervised learning for different tasks of behavior prediction. The model is scalable to allow some add-on modules to be trainable without affecting others, and is explainable to identify brain structures responsible for individualized behavioral prediction.Introduction

Resting state fMRI (rs-fMRI) contains rich information about brain networks and dynamics [10]. Recent progress has been made in using rs-fMRI to extract specific brain features that are unique to each individual and predictive of individualized traits, behaviors, or risks in diseases. Advances in deep learning and big data [5, 6, 7] further enable models and algorithms to support individualized predictions. However, such models often behave as “black boxes” that are hard to explain or generalize. To address these issues, we describe a scalable and modular system for individualized representation learning of rs-fMRI and demonstrate its utility to extract explainable brain features predictive of individual behaviors.Methods

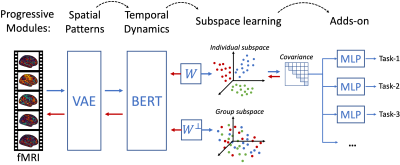

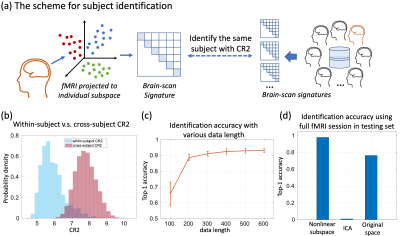

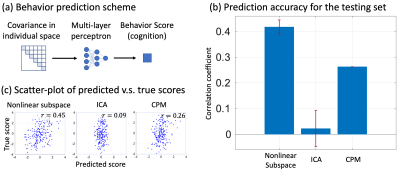

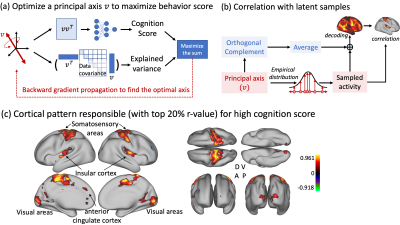

Overall, the system includes a “deep” base with “shallow” adds-on (Fig. 1). The “deep” base is trained through multiple stages of self-supervised learning with unlabeled rs-fMRI data. After the base is trained and fixed, the “shallow” adds-on are trained with supervised learning for different tasks of behavior prediction. The base includes a variational auto-encoder (VAE) for unsupervised learning of spatial representations, a Bi-directional Encoder Representations from Transformer (BERT) [4] for self-supervised learning of temporal dynamics, and a subspace learning of individualized representations. In each module, an encoder is paired with a decoder to ensure reversible transformation from the brain to the feature space and vice versa. The add-on uses a multilayer perceptron (MLP) to predict a behavioral score with individualized representation extracted from the base model.To train and evaluate the model, we used the preprocessed rs-fMRI data released by the Human Connectome Project (HCP), including 725 subjects for training, 50 for validation, and 200 for testing. The VAE was trained to encode and reconstruct the spatial pattern of fMRI using a stack of convolutional and deconvolutional layers, yielding a 256-dim latent vector for each time frame [1]. Using the output from VAE as its input, the BERT was trained to recover the missing input in a temporal sequence while the input was randomly masked out by 15% to 75%. By doing so, the BERT learned the temporal context inherent in the fMRI time series through a stack of Transformer with multi-head self-attention. The latent vectors from BERT were used to learn two orthogonal subspaces: a 32-dim “individual subspace” where individual variation was maximized and its orthogonal complement “group subspace” where individual variation was minimized (Fig. 3a). For this purpose, the variation between individuals was quantified as the coding rate reduction (CR2) [2]. Furthermore, we computed and vectorized the covariance matrix of the latent representations embedded in the individual subspace and used the resulting vector as the feature unique to each individual brain. Using this feature, an MLP was trained to predict 12 behavioral traits in the cognitive domain. The performance of prediction was evaluated as the correlation between the predicted and measured behavioral scores. We also identified the principal basis of the individual subspace responsible for the behavioral prediction and visualized its corresponding cortical pattern as decoded by the model (Fig. 5a).

Results

After training, the BERT was able to recover fMRI patterns at missing time points (Fig. 2a), and outperformed bilinear and nearest neighborhood interpolations (Fig. 2b). The covariance of the latent representations in the individual subspace was more distinctive between subjects than within subjects (Fig. 3b). It could be used to identify each individual [11] out of 200 individuals even when the duration of fMRI was only 3.5 minutes. Its top-1 accuracy (0.97) was significantly higher than those based on the covariance between independent components (0.01) or the connectome (0.76) (Fig. 3d). The model was also able to predict the 1st principle component of 12 behavioral scores with a much higher correlation (r=0.41) than the state-of-the-art connectome-based predictive modeling method (r=0.26) (Fig. 4) [3, 12]. The cortical pattern responsible for individualized behavior prediction shows a distributed network including the primary areas involved in exteroception, interoception, and cognition (Fig. 5c).Conclusion

The model described here supports self-supervised learning of the feature representation that is unique to each individual brain and predictive of individual behaviors. The expected advantages of the model include: 1) it is generalizable and unbiased by limited labels in datasets, 2) it is explainable for identifying brain structures responsible for individualized behavioral prediction, 3) it is modular and scalable to allow some modules to be trainable without affecting others. These properties merit future studies to identify the defining brain features that distinguish various populations or individuals in different ages, diseases, or with different socioeconomic and genetic factors [8, 9, 13, 14, 15].Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

[1] Kim, Jung-Hoon, Yizhen Zhang, Kuan Han, Zheyu Wen, Minkyu Choi, and Zhongming Liu. "Representation learning of resting state fMRI with variational autoencoder." NeuroImage 241 (2021): 118423.

[2] Yu, Yaodong, Kwan Ho Ryan Chan, Chong You, Chaobing Song, and Yi Ma. "Learning diverse and discriminative representations via the principle of maximal coding rate reduction." Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33 (2020): 9422-9434.

[3] Finn, Emily S., and Peter A. Bandettini. "Movie-watching outperforms rest for functional connectivity-based prediction of behavior." NeuroImage 235 (2021): 117963.

[4] Devlin, Jacob, Ming-Wei Chang, Kenton Lee, and Kristina Toutanova. "Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding." arXiv preprint arXiv:1810.04805 (2018).

[5] Plis, Sergey M., Devon R. Hjelm, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Elena A. Allen, Henry J. Bockholt, Jeffrey D. Long, Hans J. Johnson, Jane S. Paulsen, Jessica A. Turner, and Vince D. Calhoun. "Deep learning for neuroimaging: a validation study." Frontiers in neuroscience 8 (2014): 229.

[6] Kim, Junghoe, Vince D. Calhoun, Eunsoo Shim, and Jong-Hwan Lee. "Deep neural network with weight sparsity control and pre-training extracts hierarchical features and enhances classification performance: Evidence from whole-brain resting-state functional connectivity patterns of schizophrenia." Neuroimage 124 (2016): 127-146.

[7] Dinsdale, Nicola K., Emma Bluemke, Vaanathi Sundaresan, Mark Jenkinson, Stephen M. Smith, and Ana IL Namburete. "Challenges for machine learning in clinical translation of big data imaging studies." Neuron (2022).

[8] Leonardsen, Esten H., Han Peng, Tobias Kaufmann, Ingrid Agartz, Ole A. Andreassen, Elisabeth Gulowsen Celius, Thomas Espeseth et al. "Deep neural networks learn general and clinically relevant representations of the ageing brain." NeuroImage 256 (2022): 119210.

[9] Heo, Keun-Soo, Dong-Hee Shin, Sheng-Che Hung, Weili Lin, Han Zhang, Dinggang Shen, and Tae-Eui Kam. "Deep attentive spatio-temporal feature learning for automatic resting-state fMRI denoising." NeuroImage 254 (2022): 119127.

[10] Allen, Elena A., Eswar Damaraju, Sergey M. Plis, Erik B. Erhardt, Tom Eichele, and Vince D. Calhoun. "Tracking whole-brain connectivity dynamics in the resting state." Cerebral cortex 24, no. 3 (2014): 663-676.

[11] Finn, Emily S., Xilin Shen, Dustin Scheinost, Monica D. Rosenberg, Jessica Huang, Marvin M. Chun, Xenophon Papademetris, and R. Todd Constable. "Functional connectome fingerprinting: identifying individuals using patterns of brain connectivity." Nature neuroscience 18, no. 11 (2015): 1664-1671.

[12] Shen, Xilin, Emily S. Finn, Dustin Scheinost, Monica D. Rosenberg, Marvin M. Chun, Xenophon Papademetris, and R. Todd Constable. "Using connectome-based predictive modeling to predict individual behavior from brain connectivity." nature protocols 12, no. 3 (2017): 506-518.

[13] He, Tong, Ru Kong, Avram J. Holmes, Minh Nguyen, Mert R. Sabuncu, Simon B. Eickhoff, Danilo Bzdok, Jiashi Feng, and BT Thomas Yeo. "Deep neural networks and kernel regression achieve comparable accuracies for functional connectivity prediction of behavior and demographics." NeuroImage 206 (2020): 116276.

[14] Gritsenko, Andrey, Martin Lindquist, and Moo K. Chung. "Twin classification in resting-state brain connectivity." In 2020 IEEE 17th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), pp. 1391-1394. IEEE, 2020.

[15] Weis, Susanne, Kaustubh R. Patil, Felix Hoffstaedter, Alessandra Nostro, BT Thomas Yeo, and Simon B. Eickhoff. "Sex classification by resting state brain connectivity." Cerebral cortex 30, no. 2 (2020): 824-835.

Figures