1022

Real-time automatic field-of-view adjustment in fetal MR scans using Gadgetron

Sara Neves Silva1, Jordina Aviles Verdera1, Raphaël Tomi-Tricot2,3, Radhouene Neji2,3, Thomas Wilkinson1, Valéry Ozenne4, Alexander Lewin5, Lisa Story1, Enrico De Vita2, Mary Rutherford1, Kuberan Pushparajah2, Jo Hajnal1, and Jana Hutter1

1Perinatal Imaging & Health, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3MR Research Collaborations, Siemens Healthcare Limited, Frimley, United Kingdom, 4Université de Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France, 5Forschungszentrum Jülich, Jülich, Germany

1Perinatal Imaging & Health, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 2Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering & Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 3MR Research Collaborations, Siemens Healthcare Limited, Frimley, United Kingdom, 4Université de Bordeaux, Bordeaux, France, 5Forschungszentrum Jülich, Jülich, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Fetus

MRI provides an ideal tool for characterising fetal brain development and growth. It is, however, a relatively slow imaging technique and therefore extremely susceptible to subject motion. To address this challenge, we are developing an intrinsically motion-robust deep-learning-based fetal MRI method to achieve real-time fetal head tracking and update the acquisition geometry prospectively. Our method uses Gadgetron for real-time reconstruction of the scans and a 3D UNet for fetal head position location and motion estimation. Real-time tracking and correction for functional fetal MRI was demonstrated both in controlled phantom setups and in fetal MRI cases.Introduction

MRI provides an ideal tool for characterising fetal brain development. It is, however, a relatively slow imaging technique and therefore extremely susceptible to unpredictable fetal motion. Thereby, rapid single-shot acquisitions are chosen to freeze the motion during the readout of each slice, followed by post-processing techniques (SVR [1]). The most commonly used functional contrasts in fetal MRI are T2* relaxometry, exploiting the blood oxygen level-dependent effect to assess oxygenation [2], and Diffusion MRI (dMRI), offering insight into microstructure [3]. Both techniques provide crucial non-invasive insights but rely even heavier than anatomical scans on time-series data with the acquisition of the same slice stack locations multiple times. This renders these techniques particularly susceptible to inter-volume motion. Prospective motion-correction is therefore a crucial step to improve spatio-temporal analysis. We are developing an intrinsically motion-robust deep-learning-based fetal MRI method to achieve real-time (intra-scan) fetal head position and motion estimation and correction.Methods

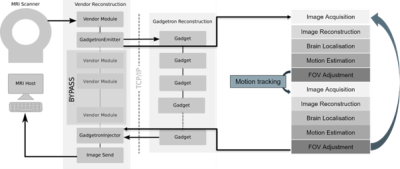

The process is schematically illustrated in Figure 1. The data is acquired using a gradient-echo single-shot EPI sequence on a 3T scanner (MAGNETOM Vida, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany): TR=11.5 s, voxel size=3.0x3.0x3.0 mm3, 34 repetitions, up to 68 slices, TE=90 ms. Intrinsic navigator images (EPI) are acquired – the target scan is simultaneously used for detecting the changes in head position and visualising the brain in BOLD MRI and dMRI to monitor cerebral development in-utero. The process is implemented on a 3T scanner (MAGNETOM Vida, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) for single shot gradient echo EPI ready for functional assessments. Key parameters are: TR=11.5 s, voxel size=3.0x3.0x3.0 mm3, 34 repetitions, up to 68 slices, TE=90 ms. The target scan is simultaneously used for detecting the changes in head position and visualising the brain in BOLD MRI and dMRI to monitor cerebral development in-utero. Thus these are intrinsic navigator images. The entire pipeline is illustrated in Figure 1.1) The Siemens raw readouts are converted to ISMRMRD format and exported to Gadgetron [4] during the scan, to be 2) reconstructed using off-the-shelf Gadgets. 3) The object position estimation was achieved using either an intensity-based segmentation method (phantom) or a pre-trained 3D-UNet [5] (fetus) to extract the fetal brain location in each repetition. The UNet model was trained on a range of gradient-echo ssEPI scans deliberately varying in field strength (1.5T / 3T), echo time, resolution (2/2.5/3 mm isotropic) acceleration factor (none, 2, 3), gestational age (19-40 weeks), and fetal health (control cases, fetal growth restriction, prolonged preterm rupture of the membranes, etc.) to increase robustness of the network. 4) The object locations were then estimated by extracting the centre-of-mass (CoM) of each segmentation at each consecutive time point (n). The translational displacement between CoM of segmentations n and n-2 was stored in the dynamic image header, sent back to the scanner with the respective image N, accessed by the sequence and used in the acquisition to adapt the next repetition.Results

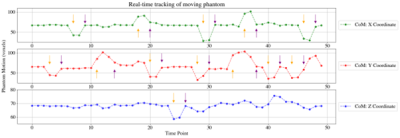

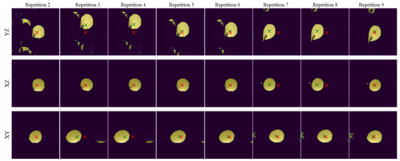

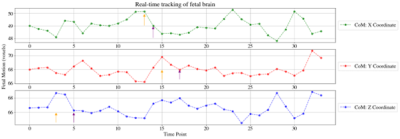

Reconstruction and intensity-based localisation were successfully performed in real-time in both the phantom (Fig. 3) and fetal (Fig. 5) experiments. The CoM coordinates extracted from the predicted segmentations are plotted for the phantom experiment in Figure 2. It shows a translational displacement in the X-coordinate of the segmentation between repetitions 6 and 7 (marked with an orange arrow), followed by an image FoV shift in repetition 9 (purple arrow) that re-centres the scan to the moved position of the phantom. FoV adjustments were also observed in repetitions 20, 31, 38, and 48 following applied motion two repetitions prior. Similarly, Fig. 2b and 2c shows FoV adaptions for the Y and Z coordinates, respectively, and in each case there is a phantom shift in the FoV, and two dynamics later the FoV shift to match. Figure 3 shows the corresponding image views for the phantom, with the green cross marking its detected CoM and the red cross showing the current FoV centre. Figure 4 shows the translational motion in XYZ directions for a fetal subject, and Figure 5 shows the corresponding image view.Discussion and Conclusion

Real-time tracking and correction for functional fetal MRI was demonstrated both in controlled phantom setups and fetal MRI cases. Future work includes adding rotational motion tracking, as well as fine-tuning the pipeline to eliminate any delays. While previous work, focusing on high resolution anatomical fetal data, has shown successful real-time identification of motion-corrupted planes [4], the use of a ML-framework to correct fetal motion in real-time in EPI-based sequences is novel and opens up a wide range of future applications, such as dynamic T2* and T1 imaging e.g. during maternal hyperoxygenation experiments and diffusion MRI.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the EPSRC Doctoral Training Programme EP/R513064/1, the NIH Human Placenta Project grant 1U01HD087202-01 (Placenta Imaging Project (PIP)), a Sir Henry Wellcome Fellowship, a UKRI FL fellowship and by core funding from the Wellcome/EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering [WT203148/Z/16/Z] and by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Biomedical Research Centre based at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College London and the NIHR Clinical Research Facility. The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Gadgetron group, particularly Michael Hansen and Hui Xue, and the radiographers, midwives and obstetricians who have contributed to this work.References

[1] A Uus et al., IEEE Trans Med Imaging, 2020, 39(9): 2750- 2759. [2] W You et al, Radiology, 2020, 294(1):141-148. [3] D Le Bihan et al., Radiology, 1986, 161(2):401-7. [4] MS Hansen et al., Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 69(6):1768-1776, 2012. [5] A Uus et al., NeurIPS, 2020. [6] A Singh et al., IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 39(11):3523-3534, 2020.Figures

Figure 1: Schematic overview of the pipeline adapted from Hui Xue, IceGadgetron, 2022, https://github.com/NHLBI-MR/IceGadgetron, illustrating the data acquisition, image reconstruction, fetal brain localisation, and the real-time change in FoV.

Figure 2: Calculated centre-of-mass coordinates in all three axes are depicted for the phantom experiment. Orange arrows indicate the detected motion, and purple arrows the corresponding automatic FoV correction, which happens two dynamics later.

Figure 3: A sequence of images illustrated motion tracking for the phantom experiment showing all three planes. The red cross marks the current centre of the image FoV, the green cross shows the current detected phantom CoM. At each moment event, the shift in the green cross is detected by the system and 2 dynamics later a corresponding FoV shift is introduced.

Figure 4: Calculated centre-of-mass coordinates in all three axes are depicted for the fetal experiment. Dynamics where the effect of motion is observed are indicated with orange arrows, and purple arrows indicate the repetitions where the automatic FoV correction was applied, two dynamics later.

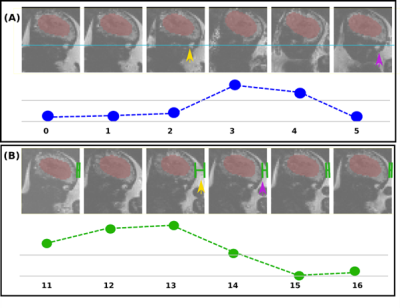

Figure 5: Consecutive dynamics from one plane are illustrated for the fetal experiment. A) Head translation is observed between repetitions 2-3 (orange arrow) and corrected with FoV adjustment two dynamics later (purple arrow), as observed in the re-alignment of the fetal eye (blue line) to the first three dynamics of the scan. B) Head motion is observed in repetition 13 with larger portion of amniotic fluid visible surrounding the fetal head when compared to previous two repetitions; FoV adjusted in time point 15 with similar portion of visible fluid to repetition 11 (green lines).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1022