1021

Motion Estimation and Retrospective Correction in 2D Cartesian Turbo Spin Echo Prostate Scans1Siemens Medical Solutions, USA, Boston, MA, United States, 2Siemens Healthcare GmbH, Erlangen, Germany, 3Siemens Medical Solutions, USA, Salt Lake City, UT, United States, 4Siemens Medical Solutions, USA, Austin, TX, United States, 5Department of Radiology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States, 6Department of Radiology, A. A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 7Harvard-MIT Health Sciences and Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Prostate, MR Value, Motion Correction, Body, Clinical Applications, Prostate

Non-rigid patient motion is commonly encountered in clinical settings and can degrade the diagnostic quality of MR exams. We apply the SAMER retrospective method for 2D TSE/FSE prostate imaging to quantify and correct for bulk motion in the abdomen. SAMER utilizes a rapid low-resolution scout scan and a small number of calibration samples for separable motion estimation. In controlled phantom and in vivo experiments, SAMER enabled accurate motion parameter estimation across multiple motion patterns. In addition, we demonstrate improved image homogeneity and spatial resolution when SAMER is used for correction of non-rigid motion in the prostate.Purpose

Subject motion in MRI can result in poor image quality, repeat exams, and significant costs to patient safety and institutions1. Many attempts have been made to detect and correct for motion2–11 but wide-spread adoption has been limited, especially in 2D Cartesian sequences which play an essential role in the majority of MR exams.The recently proposed SAMER method utilizes a rapid low-resolution scout scan in combination with a small number of calibration samples for accurate motion estimation with minimal effect on image contrast12,13. SAMER has led to promising results in neuro-imaging but has not been evaluated in body applications where non-rigid motion from breathing and peristalsis is unavoidable.

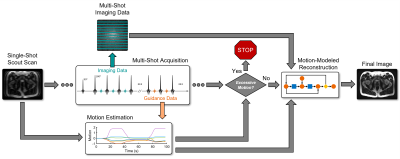

In this work we apply SAMER for 2D TSE/FSE prostate imaging in order to quantify and correct for bulk motion in the abdomen. We show through rigid-body phantom and non-rigid in vivo 2D TSE motion experiments, that SAMER provides accurate estimation of bulk motion. These motion estimates can be computed concurrently with the acquisition to facilitate real-time avoidance of full scan repeats or for improved image quality through motion-modeled reconstructions (Fig. 1).

Methods

Data AcquisitionData were acquired using a prototype 2D TSE sequence modified from the standard vender sequence to acquire a low-resolution single-shot scout image and pairs of additional phase encoding lines, referred to as guidance lines13. Importantly, the SAMER method allowed the imaging lines to be acquired in the same order as the standard sequence to maintain contrast and motion sensitivity.

Motion Estimation and Correction

Following the SAMER method12,13, motion parameters for each shot (TR) were estimated by minimizing data-consistency between measured guidance-line data and synthetic data generated from the scout image. Specifically, the motion parameters from shot $$$t$$$, were computed by solving$$\min_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\left\|\boldsymbol{d}_t^{(\mathrm{g})}-\Omega_{\mathrm{g}}\mathrm{FCM}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\boldsymbol{\rho}_{\mathrm{s}}\right\|_2^2,$$where $$$\boldsymbol{\rho}_{\mathrm{s}}$$$ is the scout image vector, $$$\boldsymbol{d}_t^{(\mathrm{g})}$$$ is the guidance line data from shot $$$t$$$, $$$\mathrm{M}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}}$$$ is the motion operator for motion parameters $$$\boldsymbol{\theta}$$$, $$$\Omega_{\mathrm{g}}$$$ is the k-space sampling mask for the guidance lines, and $$$\mathrm{F}$$$ and $$$\mathrm{C}$$$ the Fourier transform and coil sensitivity operators, respectively.

A key aspect of the SAMER method is that the motion parameter estimations across the shots are decoupled which allows for parameters to be estimated as soon as the guidance-line data become available. Furthermore, the computational scalability of SAMER allows for shot motion parameters to be estimated concurrently with the data acquisition.

Given estimates of the motion parameters from each shot, retrospective motion-mitigated reconstructions can be generated by solving a similar optimization problem, i.e.,$$\min_{\boldsymbol{\rho}}\sum_t\left\|\boldsymbol{d}_t^{(\mathrm{i})}-\Omega_t\mathrm{FCM}_{\boldsymbol{\theta}_t}\boldsymbol{\rho}\right\|_2^2$$where $$$\boldsymbol{d}_t^{(\mathrm{i})}$$$ and $$$\Omega_t$$$ are the imaging data and sampling mask for shot $$$t$$$, respectively.

Phantom and In Vivo Motion Experiments

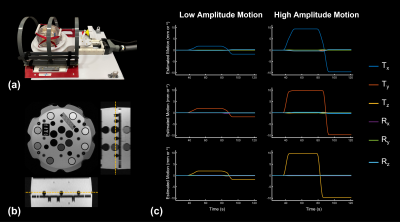

Phantom experiments were performed to evaluate the accuracy of rigid-body motion estimates. The NIST/ISMRM system phantom14 was placed in an MR-compatible linear motion stage15 (Fig. 2a-b) that was programmed to perform stepwise translations during acquisitions. Two trajectories, low- and high-amplitude (±2 and ±10 mm, respectively), were performed along each axis.

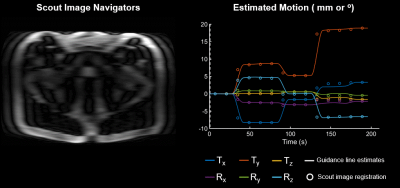

In vivo validation experiments were performed on healthy subjects instructed to perform various forms of motion. In one experiment additional scout scans were acquired during every-other shot of the acquisition. These additional scout images were registered to the original scout image to generate a set of “gold-standard” motion parameters for comparison with those estimated from the guidance-line data.

Both phantom and in vivo data were acquired using an 18-channel flexible body coil on a 3T system (MAGNETOM Vida, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with IRB approval and the following parameters: TR/TE = 7000/180 ms, FoV = 180 x 180 mm2, No. slices = 26, slice thickness = 3 mm, matrix size = 320 x 240, RO/PE oversampling factors = 2/3, PE undersampling factor = 2, flip angle = 160o.

Results

The results of phantom validation experiments performed using the linear motion stage are shown in Fig. 2. Both low- and high-amplitude translational motion along each axis could be estimated with sub-millimeter/degree accuracy.Figure 3 summarizes an in vivo experiment performed with scout scans interleaved between each shot. Good agreement is achieved between the motion parameters estimated using the guidance-lines and the ground-truth registration-based parameters.

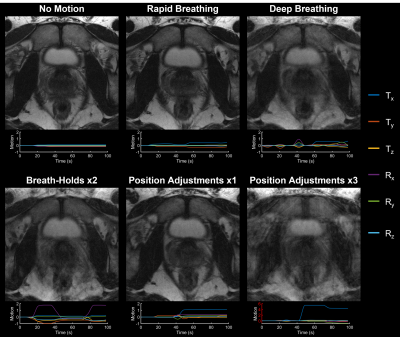

The motion-corrupted images and estimated bulk motion from in vivo experiments performed with various forms of instructed motion are provided in Fig. 4. SAMER shows sensitivity to a wide range of motion patterns and severity of artifacts.

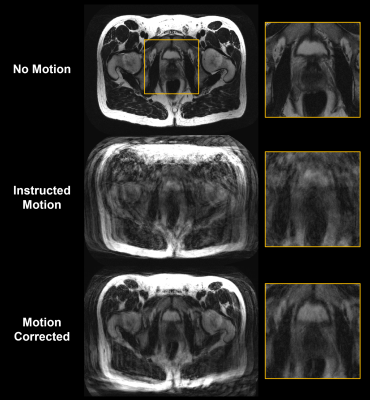

Finally, the guidance-line based motion parameters from Fig. 3 were used for retrospective motion correction. Figure 5 illustrates the potential image quality improvement when assuming bulk motion correction for prostate imaging. The motion-corrected image showed a marked reduction in artifacts compared to the uncorrected image, especially in regions where pelvic motion was approximately rigid (see scout navigator images in Fig. 3).

Conclusions

In rigid-body phantom and non-rigid in vivo 2D TSE prostate motion experiments, SAMER can provide accurate “on-the-fly” estimation of bulk motion for real-time avoidance of full scan repeats or for improved image quality through motion-modeled reconstructions.Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by NIH research grants: 1P41EB030006-01, 5U01EB025121-03, and through research support provided by Siemens Medical Inc.References

1. Andre JB, Bresnahan BW, Mossa-Basha M, et al. Toward Quantifying the Prevalence, Severity, and Cost Associated With Patient Motion During Clinical MR Examinations. J Am Coll Radiol. 2015;12(7):689-695. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2015.03.0072. Zaitsev M, Maclaren J, Herbst M. Motion artifacts in MRI: A complex problem with many partial solutions: Motion Artifacts and Correction. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015;42(4):887-901. doi:10.1002/jmri.24850

3. Zaitsev M, Dold C, Sakas G, Hennig J, Speck O. Magnetic resonance imaging of freely moving objects: prospective real-time motion correction using an external optical motion tracking system. NeuroImage. 2006;31(3):1038-1050. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.01.039

4. Maclaren J, Armstrong BSR, Barrows RT, et al. Measurement and Correction of Microscopic Head Motion during Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Brain. Hess CP, ed. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(11):e48088. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0048088

5. Frost R, Wighton P, Karahanoğlu FI, et al. Markerless high‐frequency prospective motion correction for neuroanatomical MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2019;82(1):126-144. doi:10.1002/mrm.27705

6. Aksoy M, Forman C, Straka M, et al. Real-time optical motion correction for diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2011;66(2):366-378. doi:10.1002/mrm.22787

7. Derbyshire JA, Wright GA, Henkelman RM, Hinks RS. Dynamic scan-plane tracking using MR position monitoring. J Magn Reson Imaging. 1998;8(4):924-932. doi:10.1002/jmri.1880080423

8. White N, Roddey C, Shankaranarayanan A, et al. PROMO: Real-time prospective motion correction in MRI using image-based tracking. Magn Reson Med. 2010;63(1):91-105. doi:10.1002/mrm.22176

9. Ooi MB, Aksoy M, Maclaren J, Watkins RD, Bammer R. Prospective motion correction using inductively coupled wireless RF coils: Prospective Motion Correction Using Wireless Markers. Magn Reson Med. 2013;70(3):639-647. doi:10.1002/mrm.24845

10. Tisdall MD, Hess AT, Reuter M, Meintjes EM, Fischl B, van der Kouwe AJW. Volumetric navigators for prospective motion correction and selective reacquisition in neuroanatomical MRI: Volumetric Navigators in Neuroanatomical MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2012;68(2):389-399. doi:10.1002/mrm.23228

11. Wallace TE, Afacan O, Waszak M, Kober T, Warfield SK. Head motion measurement and correction using FID navigators. Magn Reson Med. 2019;81(1):258-274. doi:10.1002/mrm.27381

12. Polak D, Splitthoff DN, Clifford B, et al. Scout accelerated motion estimation and reduction (SAMER). Magn Reson Med. August 2021:mrm.28971. doi:10.1002/mrm.28971

13. Polak D, Hossbach J, Splitthoff DN, et al. Motion guidance lines for robust data-consistency based retrospective motion correction in 2D and 3D MRI. Magn Reson Med. In Press. doi:10.1002/mrm.29534

14. Stupic KF, Ainslie M, Boss MA, et al. A standard system phantom for magnetic resonance imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2021;86(3):1194-1211. doi:10.1002/mrm.28779

15. Tavallaei MA, Johnson PM, Liu J, Drangova M. Design and evaluation of an MRI-compatible linear motion stage: MRI-compatible linear motion stage. Med Phys. 2015;43(1):62-71. doi:10.1118/1.4937780

Figures

Figure 1: SAMER can facilitate real-time avoidance of full scan repeats or provide improved image quality through motion-modeled reconstructions. SAMER acquires a single-shot, low-resolution scout image at the beginning of the scan and a set of additional phase encodings (guidance lines13) during each shot. The scout and guidance data enable concomitant motion-estimation during the scan. If excessive motion is detected, the acquisition can be aborted to save scan time, otherwise the motion can be incorporated into the reconstruction to reduce artifacts in the final image.

Figure 5: Rigid-body motion-corrected reconstruction of data acquired from a healthy volunteer performing the instructed motion shown in Fig. 3. The motion-corrected reconstruction shows a marked reduction in the level of motion artifacts present in the motion-corrupted image, especially in regions where pelvic motion was approximately rigid (see scout navigator images in Fig. 3) and demonstrates the potential image quality improvement when assuming bulk motion correction for prostate imaging.