1019

Three-dimensional rigid head motion correction using the Beat Pilot Tone and Gaussian Processes

Niek R.F. Huttinga1, Suma Anand2, Cornelis A.T. van den Berg1, Alessandro Sbrizzi1, and Michael Lustig2

1Computational Imaging Group for MR therapy & Diagnostics, Department of radiotherapy, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands, 2Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

1Computational Imaging Group for MR therapy & Diagnostics, Department of radiotherapy, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands, 2Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences, University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Motion Correction, Brain; Pilot Tone; Surrogate Signals

In this work we propose a framework based on Gaussian Processes to extract quantitative motion information from Beat Pilot Tones and subsequently correct rigid head motion in 2D and 3D. In a calibration phase, low-resolution images are acquired and registered to build a training set. Next, Gaussian Processes are trained to infer rigid parameters from multi-channel BPTs, exploiting automatic relevance determination of input channels. In the inference phase, rigid parameters are inferred per readout from the BPT, and high-resolution scans are corrected for motion. In practice the method could reduce the need for anesthetics and/or re-scans in e.g. pediatric patients.Introduction

Magnetic Resonance Imaging has enabled high-resolution imaging with excellent soft-tissue contrast, but is inherently sensitive to subject motion. Several strategies for motion correction exist, which frequently exploit surrogate signals (cameras[1], Pilot Tones (PT)[2], (self-)navigation MR-data[3],[4]).The Pilot Tone (PT) is a constant-amplitude RF-tone transmitted during MRI acquisition, which is modulated under the effect of motion, and eventually received by the MR-receiver coil array. However, the tone’s transmit frequency must lie within the MR receiver bandwidth, which inherently limits its sensitivity to motion[5]. Recently, the Beat Pilot Tone (BPT)[5] was proposed as an alternative, which overcomes this by using two microwave tones (2.4GHz, 2.5278GHz) with a frequency difference within the MR bandwidth. These tones are passively mixed at the coil preamplifiers by nonlinear intermodulation, generating a beat frequency tone that is then processed by the receiver chain. Previous results[5] have shown that BPT has greater sensitivity to head motion compared to PT at 3T.

BPT signals are, however, qualitative in nature, while motion correction requires quantitative displacement information to correctly re-align the data. In this work, we propose a method to extract this information from multi-channel BPT using a probabilistic machine learning framework called Gaussian Processes (GP)[6]. GPs can perform rapid non-linear regression on a small number of samples, thereby automatically determining the relevance of the different input channels for regression. The feasibility of motion correction with the extracted signals is demonstrated in 2D and 3D tests.

Methods

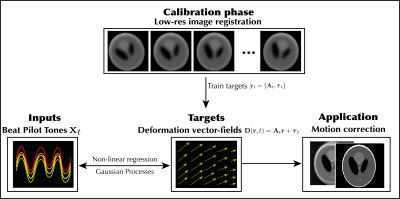

GPs operate in two steps: 1) a training phase in the order of seconds to estimate an optimal kernel; 2) an inference phase to predict for each input a new output and a measure of uncertainty on the predicted output.Here, GPs were trained to infer rigid motion parameters (output) from multi-channel BPT data (input) for each readout to eventually perform motion correction. We followed two steps with two separate datasets as explained below and in Figure 1.

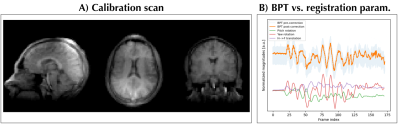

To extract the BPT, an IFFT was taken along the readout direction, and the energy was computed over a 25 kHz window around the BPT’s transmission frequency. Gradient-induced artifacts were removed from the raw BPT by subtracting an approximation of the BPT-signal as a low-order polynomial function of trajectory-endpoint coordinates (Figure 3B).

Step 1: Calibration acquisition, Image registration, GP training

First, a low-resolution time-resolved sequence was acquired during BPT transmission which probes all degrees-of-freedom of motion. Next, the BPT was extracted and image registration was performed to construct temporally synchronized training data $$$\{\mathbf{x}_t,\mathbf{y}_t\}_{t=1}^{120}$$$ with pre-processed BPT-signals $$$\mathbf{x}_t$$$ and rigid motion parameters $$$\mathbf{y}_t$$$. Here, $$$\mathbf{y}_t:=\{\mathbf{A}_t,\boldsymbol{\tau}_t\}$$$ warp a moving image to a fixed image through motion-fields $$$\mathbf{D}(\mathbf{r},t)=\mathbf{A}_t\mathbf{r}+\tau_t$$$. Finally, a GP was trained to infer $$$\mathbf{y}_t$$$ from $$$\mathbf{x}_t$$$ with GPy[8].

Step 2: High-res acquisition, GP inference, motion correction

Next, high-resolution data was acquired during motion with the BPT. The BPT was pre-processed as above and the trained GP was employed to infer rigid motion parameters $$$\mathbf{y}_t$$$ from the BPT $$$\mathbf{x}_t$$$ for each readout. Subsequently, motion correction was performed in k-space; first translation with a linear phase ramp, and finally rotation with a density-compensated adjoint NUFFT reconstruction using the motion-corrected trajectory $$$\mathbf{A}_t^T\mathbf{k}$$$. This correction follows from the model derivation in[9].

Experiments

The method was applied to both 2D and 3D rigid in-vivo head motion correction. The BPT transmit antenna was attached to the bore over the head coil[5].For 2D correction, data were continuously acquired during purely axial-plane motion with 2D Cartesian bSSFP (TR=4.6ms, FA=35 deg., FOV=50cm, resolution=2.2mm, BW=250kHz, time=2min, frame-rate=1.1s; Figure 2). Low-resolution calibration data were retrospectively generated to simulate a time-resolved 3D scenario.

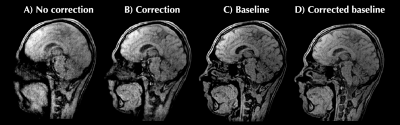

For 3D correction, low-resolution (3mm) calibration data were acquired during motion with a bit-reversed 3D UTE radial trajectory (TR=3.4ms,FA=5, 40000 spokes, BW=250kHz,time=2.3min)[11], and a 3D time-resolved MRI was reconstructed with PICS[12] (Figure 3). Next, high-resolution (1mm) 3D UTE radial data was acquired with a similar protocol and separated in two parts: a motion-free part to serve as baseline, a motion-corrupted part with similar motion as the calibration data.

Results

Figure 2 shows the results for in-plane 2D motion. The image is qualitatively improved over the reference dynamic from the time-resolved sequence.Figure 3 shows the 3D motion correction using radial UTE data (Figure 4). Image quality is improved using the motion correction, and approaches the motion-free baseline. Moreover, the “sanity check” is positive; motion correction applied to motion-free data does not reduce the quality.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this work we have proposed a framework based on Gaussian Processes to extract quantitative motion information from Beat Pilot Tones and subsequently correct rigid head motion in 2D and 3D. In practice, motion correction could be performed for e.g. pediatric subjects to alleviate the need of re-scans and/or anesthetics which suppress movement. The current proof-of-concept used two 3D radial UTE scans: low-resolution calibration and high-resolution inference. The former allows retrospective calibration of the temporal/spatial resolution to resolve the motion. The high-resolution inference scan could be replaced with any clinical protocol, as long as the BPT is consistent with the training set. Additionally, the GP inference speeds (few milliseconds per readout) indicate the potential for real-time prospective motion correction. Finally, the method could be extended to non-rigid motion correction with more advanced models.[4,7]Acknowledgements

This work was performed as part of a research visit at the University of California, Berkeley. The first author gratefully acknowledges financial support through the awarded KNAW Van Leersum Grant of the KNAW Medical Sciences Fund, the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts & Sciences. The second and last author gratefully acknowledge the financial support by GE Healthcare, NIH R01MH127104, U24EB029240, U01EB029427.References

- M. Hoogeman, J.-B. Prévost, J. Nuyttens, J. Pöll, P. Levendag, and B. Heijmen, “Clinical accuracy of the respiratory tumor tracking system of the cyberknife: assessment by analysis of log files,” Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys., vol. 74, no. 1, pp. 297–303, 2009.

- P. Speier, M. Fenchel, and R. Rehner, “PT-Nav: a novel respiratory navigation method for continuous acquisitions based on modulation of a pilot tone in the MR-receiver,” Magn Reson Mater Phys Biol Med, vol. 28, pp. S97–S98, 2015.

- M. D. Tisdall, A. T. Hess, M. Reuter, E. M. Meintjes, B. Fischl, and A. J. van der Kouwe, “Volumetric navigators for prospective motion correction and selective reacquisition in neuroanatomical MRI,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 68, no. 2, pp. 389–399, 2012.

- N. R. F. Huttinga, T. Bruijnen, C. A. T. van den Berg, and A. Sbrizzi, “Nonrigid 3D motion estimation at high temporal resolution from prospectively undersampled k-space data using low-rank MR-MOTUS,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 85, no. 4, pp. 2309–2326, 2021.

- S. Anand and M. Lustig, “Beat Pilot Tone: Exploiting Preamplifier Intermodulation of UHF/SHF RF for Improved Motion Sensitivity over Pilot Tone Navigators,” in ISMRM Meeting and Exhibition Abstract, 2021.

- C. E. Rasmussen, “Gaussian processes in machine learning,” in Summer school on machine learning, 2003, pp. 63–71.

- N. R. F. Huttinga, T. Bruijnen, C. A. T. van den Berg, and A. Sbrizzi, “Gaussian Processes for real-time 3D motion and uncertainty estimation during MR-guided radiotherapy,” ArXiv Prepr. ArXiv220409873, 2022.

- N. Lawrence, “GPy: A Gaussian process framework in python,” GitHub repository. GitHub, 2019. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/SheffieldML/GPy

- N. R. F. Huttinga, C. A. T. van den Berg, P. R. Luijten, and A. Sbrizzi, “MR-MOTUS: model-based non-rigid motion estimation for MR-guided radiotherapy using a reference image and minimal k-space data,” Phys. Med. Biol., vol. 65, no. 1, p. 015004, 2020.

- K. Marstal, F. Berendsen, M. Staring, and S. Klein, “SimpleElastix: A user-friendly, multi-lingual library for medical image registration,” in Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition workshops, 2016, pp. 134–142.

- K. M. Johnson, S. B. Fain, M. L. Schiebler, and S. Nagle, “Optimized 3D ultrashort echo time pulmonary MRI,” Magn. Reson. Med., vol. 70, no. 5, pp. 1241–1250, 2013.

- M. Uecker et al., “Berkeley advanced reconstruction toolbox,” in Proc. Intl. Soc. Mag. Reson. Med, 2015, vol. 23, p. 2486.

Figures

A high-level overview of the proposed method, which follows two steps: 1) a calibration phase and 2) an inference/correction phase. In the calibration phase, the BPT is acquired alongside low-resolution dynamic MR images, and ground-truth training targets are obtained through image registration. Next a GP is trained to infer those targets from BPT inputs. In the inference phase, the BPT is acquired during motion, and the trained GP is employed to infer motion parameters for every readout. Finally, the estimated motion parameters are used to perform motion correction.

Result for 2D motion correction. A) low-resolution input images used for registration and GP training. B) Static reference dynamic from 2D+t time-resolved acquisition. C) motion correction using the proposed method. D) Raw multi-channel BPT signals acquired simultaneously with the low-resolution in A. E) Comparison between raw BPT signals and rotation parameters resulting from image registration.

A) Low-resolution 3D radial UTE calibration data on which the GP for the 3D motion correction was trained. B) A comparison between pre-corrected, post-corrected BPT signals (see Methods) and rigid registration parameters. A linear correlation can be observed for some parts, while relation is less apparent in other regions; this demonstrates the need for nonlinear registration as performed by Gaussian Processes.

For 3D motion correction the calibration data comprised a low-resolution 3D radial UTE acquisition. From this 3D+t low-resolution dynamic images were reconstructed at 0.2 Hz (Fig. 4). Rigid motion parameters were extracted with registration. Inference data comprised a high-resolution 3D radial UTE acquisition starting without motion (baseline) and ending with motion. A) no correction performed; B) reconstruction with motion correction per readout; C) reconstruction of baseline ‘no-motion’ data without correction; D) sanity check: 'correction' of motion-free baseline.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/1019