1018

Spiral-In/Out MR Elastography with Fat-Water Image Reconstruction for the Quantification of Skull and Brain Motion1Department of Biomedical Engineering, University of Delaware, Newark, DE, United States, 2Department of Medicine, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Elastography, Traumatic brain injury

This study uses a novel multishot spiral-in/out fat-water magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) pulse sequence to simultaneously measure skull and brain motion in vivo in a single acquisition. Results in a healthy volunteer showed reduced transmission of motion from the skull to the brain in all three directions of motion. Additionally, the motion of the skull and brain appear to be in phase, with the scalp moving out of phase and most overall displacement in the direction of actuation. This research provides a basis for future studies quantifying skull-brain coupling with multiple actuation frequencies and excitation directions.

Introduction

The study of brain injury mechanics is currently limited by the inability to observe relative motion between the skull and brain in vivo. Imaging the displacement of bone and soft tissue simultaneously would improve the modeling of brain-skull coupling and its contribution to traumatic brain injury (TBI).1 Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE) is a noninvasive imaging technique for estimating mechanical properties in vivo, but also captures small-scale brain tissue displacement from harmonic vibration and, as such, can be used to safely examine how the brain deforms2. Simultaneously imaging skull motion with MRE is challenging due to the ultrashort T2 of cortical bone3. A potential solution to this is imaging the fatty marrow within the medullary cavity of the bone4, which in turn requires acquisition and reconstruction considerations to avoid distortion and signal loss due to the difference in resonance frequency. In this work we develop a fat-water MRE sequence with a spiral-in/out trajectory to measure relative skull-brain displacement with the goal of quantifying transmission of motion from the skull to the brain during TBI.Methods

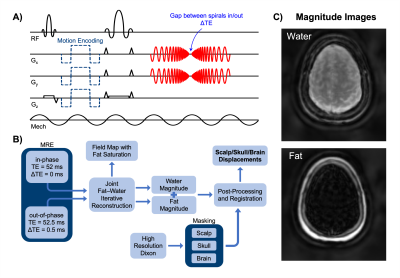

To obtain high-resolution displacement data of the brain and skull simultaneously, we combined fat-water imaging with a novel 2D multishot spiral in/out MRE sequence. Spiral-in/out is unique in its ability to employ multiple trajectories in a single excitation5, and thus achieve multiple echo times. Here, an echo time shift of 0.5 ms was built into the spiral-in/out trajectory to sample data when fat and water were both in-phase and relatively out-of-phase with each other (Figure 1).Imaging: MRE protocol parameters included 240 x 240 mm2 field-of-view, 2 mm isotropic resolution, 20 slices, TR/TE = 2400/52 ms, 4 phase offsets, and 6 spiral shots (R=2). All scanning was conducted using a Siemens 3T Prisma MRI scanner and a 20-channel head coil. Vibrations were generated at 50 Hz using a Resoundant pneumatic actuation system (Rochester, MN) and a passive pillow driver. Data was collected at both low (5 mT/m) and high (70 mT/m) motion encoding gradient amplitudes to capture rigid body motion (RBM) while avoiding temporal phase wrapping2 and to calculate mechanical properties, respectively. We also collected Dixon fat-water images with an in-plane resolution of 0.6 mm to create masks of brain, skull, and scalp to obtain displacement maps for each region of interest.

Reconstruction: A joint fat-water iterative reconstruction was used to obtain separate images for fat and water from the data with two echo times, similar to Wang, et al7. A standard system matrix for iterative MR reconstruction was divided into fat and water components, $$$A_{f}$$$ and $$$A_{w}$$$, where $$$\overrightarrow{k}_m$$$ and $$$\overrightarrow{r}_n$$$ are k-space and image-space coordinates respectively, is the phase accumulation due to field inhomogeneity, $$$t$$$ is the time at which data is sampled, and $$$\Delta\omega_{f}$$$ is the chemical shift between fat and water:

$$A_{w,mn} = e^{j2\pi(\overrightarrow{k}_m\cdot\overrightarrow{r}_n)}e^{j\omega_{n}t_{m}}$$

$$A_{f,mn} = e^{j2\pi(\overrightarrow{k}_m\cdot\overrightarrow{r}_n)}e^{j\omega_{n}t_{j}}e^{j\Delta\omega_{f}t_{m}}$$

This matrix was implemented with time segmentation and a nonuniform fast Fourier transform8. The resulting equation for separate fat and water images (below) was then solved using Fessler’s penalized least squares solver via conjugate gradient descent,9 where $$$y$$$ is the data from multiple echo times, $$$R$$$ is roughness regularization penalty, and $$$\beta$$$ is the regularization constant:

$$\hat{x}_{w},\hat{x}_f =\begin{matrix}argmin \\x_{w},x_{f} \end{matrix}{\begin{Vmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}y_{TE_{1}} \\ y_{TE_{2}} \end{bmatrix} - \begin{bmatrix}A_{w} \\A_{f} \end{bmatrix} \begin{bmatrix}x_{w} \\x_{f} \end{bmatrix} \end{Vmatrix}}^{2}_{2} + \beta(R(x_{w}) + R(x_{f}))$$

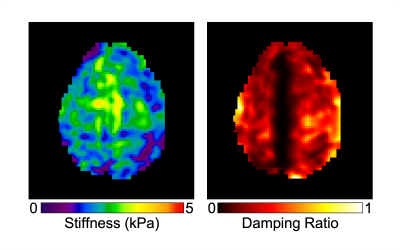

Analysis: Reconstructed phase images were processed to obtain maps of complex motion with sensitization in the x (left-right), y (anterior-posterior), and z (superior-inferior) directions. Displacement amplitude and relative phase of the harmonic motion was quantified for each point in both skull and brain. Low sensitivity data was used to estimate translational and rotational RBM of the skull and brain. High sensitivity brain displacement data was input into a nonlinear inversion algorithm (NLI)10 to calculate maps of mechanical properties, stiffness and damping ratio.

Results

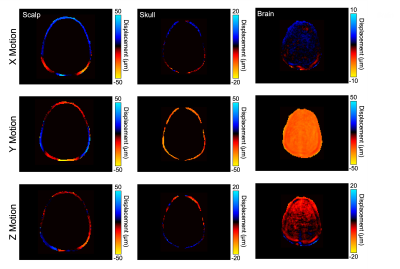

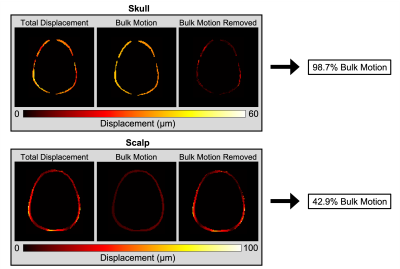

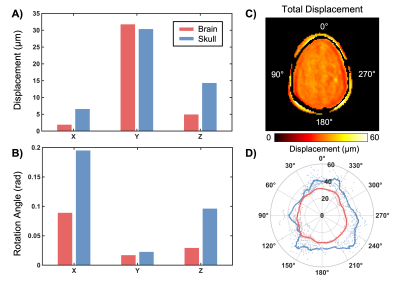

The in vivo analysis of brain and skull motion showed an overall lower displacement amplitude of the brain relative to the skull, indicating reduced transmission of motion to the brain in all three directions. Figure 2 shows the skull and brain moving roughly in phase with each other but independently of the scalp. Rigid body motion fitting showed that 98.7% of skull motion was RBM in contrast to only 42.9% of scalp motion, as expected, confirming that our acquisition was successful in isolating the skull without contamination (Figure 3). Further quantification of brain and skull rigid body displacement show the highest translational motion in y and rotational motion about the x-axis which corresponds with the direction of actuation (Figure 4). Mechanical properties calculated from NLI show high-quality property maps in a representative slice in Figure 5.Discussion & Conclusions

The fat-water spiral-in/out MRE sequence and reconstruction developed in this study was successful in measuring skull and brain displacement simultaneously. This approach allows us to improve resolution through interleaved spiral readouts11 in half the acquisition time and without the need for repeated acquisitions with separate echo times, as in previous work12. This shortened scan time will enable us to look at multiple frequencies and actuation directions to further quantify the transmission of motion from skull to brain. Future work will also incorporate dual-sensitivity motion encoding4 to obtain rigid-body measurements and mechanical property estimates simultaneously.Acknowledgements

This project was supported by NIH grant U01-NS112120, the NIH Bench-to-Bedside program, and Office of Naval Research grant N00014-22-1-2198.References

1. Bayly, P. V. et al. MR Imaging of Human Brain Mechanics In Vivo: New Measurements to Facilitate the Development of Computational Models of Brain Injury. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2021 1–16 (2021) doi:10.1007/S10439-021-02820-0.

2. Okamoto, R.J., Romano, A.J., Johnson, C.L. & Bayly, P.V. Insights Into Traumatic Brain Injury From MRI of Harmonic Brain Motion. J. Exp. Neurosci. 13, 117906951984044 (2019).

3. Bae, W. C. et al. Quantitative Ultrashort Echo Time (UTE) MRI of Human Cortical Bone: Correlation with Porosity and Biomechanical Properties. J Bone Min. Res 27, 848–857 (2012).

4. Yin, Z. et al. In vivo characterization of 3D skull and brain motion during dynamic head vibration using magnetic resonance elastography. Magn. Reson. Med. 80, 2573–2585 (2018).

5. Law, C. S. & Glover, G. H. Interleaved spiral-in/out with application to functional MRI (fMRI). Magn. Reson. Med. 62, 829–834 (2009).

6. Badachhape, A. A. et al. The Relationship of Three-Dimensional Human Skull Motion to Brain Tissue Deformation in Magnetic Resonance Elastography Studies. J. Biomech. Eng. 139, 0510021 (2017).

7. Wang, D., Zwart, N. R. & Pipe, J. G. Joint water–fat separation and deblurring for spiral imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 79, 3218–3228 (2018).

8. Sutton, B. P., Noll, D. C. & Fessler, J. A. Fast, iterative image reconstruction for MRI in the presence of field inhomogeneities. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 22, 178–188 (2003).

9. Fessler, J. A. Penalized Weighted Least-Squares image Reconstruction for Positron Emission Tomography. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 13, 290–300 (1994).

10. McGarry, M. D. J. et al. Multiresolution MR elastography using nonlinear inversion. Med. Phys. 39, 6388–6396 (2012).

11. Johnson, C. L. et al. Magnetic resonance elastography of the brain using multishot spiral readouts with self-navigated motion correction. Magn. Reson. Med. 70, 404–412 (2013).

12. Diano, A. M. et al. Quantifying Relative Displacement and Phase at the Skull-Brain Interface using MR Elastography. ISMRM 2022. https://archive.ismrm.org/2022/2248.html.

Figures

Figure 1. Sequence diagram with echo spacing to account for chemical shift between fat and water (A), flow chart of data acquisition, reconstruction, and analysis to obtain displacement fields for each region of interest (B), and resulting fat and water magnitude images (C).

Figure 2. Displacement in the x (left-right), y (anterior-posterior), and z (superior-inferior) directions at 50 Hz showing differences between scalp, skull, and brain motion.

Figure 3. Total displacement, bulk motion, and bulk motion removed of the skull and scalp showing that the skull acts as a rigid body.

Figure 4. Translational (A) and rotational (B) rigid body motion of brain and skull in each direction. Total displacement is shown with a representative mask created at the interface of the skull and brain (C). Points around the circumference of the skull were defined in terms of polar coordinates and described by their polar angle, θ (D).

Figure 5. Representative slice of mechanical property maps, stiffness and damping ratio, obtained from spiral-in/out fat-water MRE.