1009

Towards rapid and accurate navigators for motion and B0 estimation using QUEEN (QUantitatively-Enhanced parameter Estimation from Navigators)1Department of Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2Department of Electrical Engineering, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 3Biomedical Image Technologies, ETSI Telecomunicación, Universidad Politécnica de Madrid and CIBER-BNN, Madrid, Spain, 4Biomedical Engineering Department, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 5Centre for the Developing Brain, School of Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Sciences, King's College London, London, United Kingdom, 6Cognitive and Neurobiological Imaging (CNI), Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Motion Correction, Brain

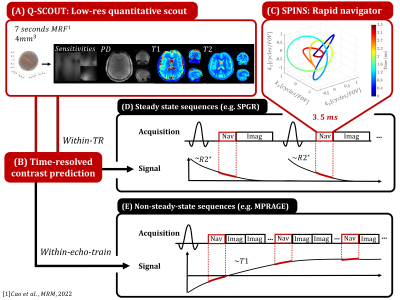

‘Scout-based’ navigators exploit correlations between navigator data and a low-resolution multi-coil pre-scan data (scout) to effectively estimate either motion or B0-perturbations. Usually, scout data has a fixed contrast, limiting their usage in estimating motion within echo-trains where contrast changes from one readout to the next (e.g. MPRAGE). Furthermore, combined motion and B0-perturbation estimation from rapid navigators has yet to be achieved. In this work, we propose a quantitative scout (Q-SCOUT) to ‘time-resolve’ navigator contrast, along with a rapid SPINS-navigator (few ms). Q-SCOUT and rapid navigator data are used in our QUEEN method to enable within-echo-train motion and B0-perturbation estimation.Introduction

MRI is susceptible to motion and B0-inhomogeneity perturbations[1]. Navigator-based techniques have been developed to estimate and correct for these, including methods that utilize a pre-scan to guide motion/B0 estimation. Within this class, the cloverleaf and spherical navigators[2-3] utilize tailored k-space trajectories to sensitize signals to rigid motion. FID multi-coil navigators [4] have been augmented with a low-resolution pre-scan ‘scout’ image to enable accurate motion[5] or B0-perturbation[6] estimation. Similarly, the “SAMER+guidance-lines”[7] approach utilizes a single-contrast scout along with 4 lines of k-space acquisition from an echo-train to achieve accurate inter-echo-train motion estimation. In this work, we propose “Quantitatively-Enhanced parameter Estimation from Navigators (QUEEN)”, to provide robust combined motion and B0-perturbation estimation for both inter- and within-echo-train correction by using a time-resolved multi-contrast scout. A short navigator of a few ms was developed and can be flexibly inserted in most sequences. QUEEN’s novel components include i) a ‘quantitative’ scout scan (Q-SCOUT), ii) time-resolved motion and B0 estimation and iii) a tailored SPINS navigator[8].Methods

Q-SCOUT:This work extends the concept of a single-contrast scout to a time-resolved quantitative scout (Q-SCOUT) that models the time-varying navigator signal (Fig1) to enable navigator usage in almost any sequence and/or timing. To correct for brain motion and B0-perturbation ($$$\delta \textbf{B}_0$$$), a low-resolution Q-SCOUT is sufficient for which fast quantitative imaging sequences such as MRF and EPTI[9,10] can be used. Fig1 showcases a 7s MRF acquisition to obtain whole-brain PD, T1, T2 and coil sensitivity information at 4mm isotropic resolution.

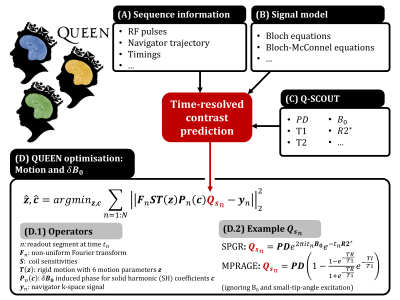

QUEEN:

Whereas the Q-SCOUT predicts the time-varying navigator signal $$$\textbf{Q}_s(t)$$$ (Fig2), QUEEN refers to the estimation of motion and $$$\delta \textbf{B}_0$$$ parameters. Navigator k-space is modeled as a time-segmented signal:

$$

\textbf{y}_n = \textbf{F}_n\textbf{ST}(\textbf{z})\textbf{P}_n(\delta \textbf{B}_0)\textbf{Q}_{s_n}\quad\quad(1)

$$

for time-segments $$$n=1:N$$$, where $$$\textbf{F}_n$$$ is the segment-dependent non-uniform Fourier transform, $$$\textbf{P}_n$$$ the induced phase $$$e^{2\pi \delta \textbf{B}_0t_n}$$$ and $$$\textbf{Q}_{s_n}$$$ the Q-SCOUT-predicted contrast at time $$$t_n$$$. $$$\textbf{T}(\textbf{z})$$$ represents the rigid motion operator (with rigid motion parameters $$$\textbf{z}$$$) and $$$\textbf{S}$$$ contains the coil sensitivities. We model $$$\delta \textbf{B}_0$$$ using a set of 2nd-order solid harmonics (SH) [11] ($$$\delta \textbf{B}_0=\textbf{Bc}$$$ with SH basis $$$\textbf{B}$$$ and coefficients $$$\textbf{c}$$$) and iteratively estimate motion and $$$\textbf{c}$$$ using the Levenberg-Marquardt algorithm:

$$

\textbf{z}^{i+1}=argmin_\textbf{z}\sum_{n=1}^{N}|| \textbf{F}_n\textbf{ST}(\textbf{z})\textbf{P}_n( \textbf{c}^{i})\textbf{Q}_{s_n}-\textbf{y}_n||^2_2\quad\quad(2)

\\\textbf{c}^{i+1}=argmin_\textbf{c}\sum_{n=1}^{N}|| \textbf{F}_n\textbf{ST}(\textbf{z}^{i+1})\textbf{P}_n( \textbf{c})\textbf{Q}_{s_n}-\textbf{y}_n||^2_2\quad\quad(3)

$$

SPINS:

The SPINS trajectory, originally designed for B1+-mitigated RF excitation, is used here due to its rapid acquisition and sensitivity to rigid motion and B0 inhomogeneity: arc-sampling at multiple radii sensitizes signal to rotation and translation whilst sampling the k-space origin at start and end results in B0 sensitivity. Acquisition time was minimized using gradient trajectory optimization[12] (Fig1).

Simulations:

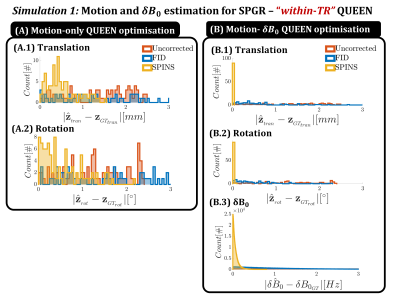

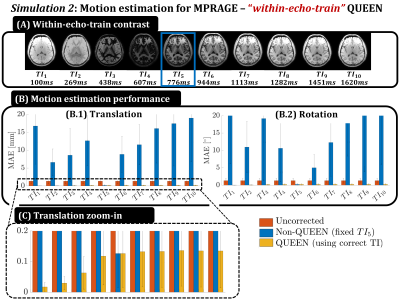

Simulation 1 compares the FID and SPINS navigator trajectory when simulating ‘within-TR’ navigator signal for an SPGR sequence (Fig2): baseline B0- and R2*-resolved signal is simulated in the presence of motion and $$$\delta \textbf{B}_0$$$. Motion is QUEEN-estimated by either ignoring $$$\delta \textbf{B}_0$$$ (“motion-only”) or joint optimization (“motion-$$$\delta \textbf{B}_0$$$ ”). Simulation 2 simulates ‘within-echo-train’ navigator signal for MPRAGE at different inversion times (TI) (Fig3). Motion is estimated using either the correct TI (Q-SCOUT+QUEEN) or a fixed TI (fixed-SCOUT+non-QUEEN). Other effects on the signal (e.g. readout RF excitations) are ignored for simplicity but can be incorporated. B0 can be ignored since MPRAGE usually uses short TEs, making the FID navigator preferable due to its arbitrary duration. By acquiring a 1ms FID navigator every 169ms, this simulation mimics high-temporal resolution within-echo-train motion estimation with minimal efficiency loss (0.5%).

In-vivo:

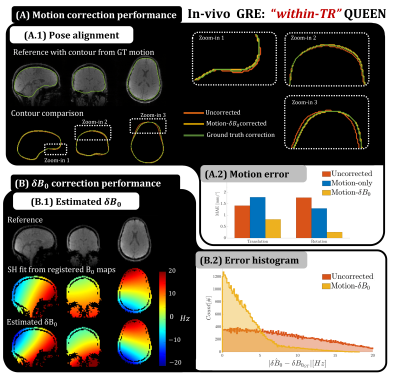

The ‘within-TR’ QUEEN was tested on a healthy volunteer by implementing the proposed SPINS in a multi-echo GRE (Fig5). Q-SCOUT data was generated at 4x4x4mm3 by retrospectively under-sampling the image acquisition and fitting B0 and R2* maps from multi-echo images. Gradient trajectories were measured using a Skope field camera[13]. Data was acquired in 1) a reference pose and 2) a different pose whilst placing the arms close to the head to induce B0 variation. QUEEN was compared to the ground truth, obtained by registering reconstructed images and B0 maps. ROVir coil compression[14] was used to suppress signal from regions of non-rigid neck motion.

Results and discussion

Results for simulation 1 are shown in Fig3, where coupling between motion and $$$\delta \textbf{B}_0$$$ estimation is observed (3.A -B). Improved estimation is obtained for the proposed “motion-$$$\delta \textbf{B}_0$$$ ” QUEEN optimization. Furthermore, SPINS outperform the FID trajectory in the presence of $$$\delta \textbf{B}_0$$$. Results for simulation 2 (Fig4) show that the time-resolved Q-SCOUT drastically improves the QUEEN motion estimation for TIs away from the fixed-SCOUT. Even with the Q-SCOUT, slight sensitivity of parameter estimation to contrast is observed (4.B). In-vivo results (Fig5) confirm improved motion estimation for the “motion-$$$\delta \textbf{B}_0$$$” QUEEN, although with reduced accuracy compared to simulations. Observed systematic signal inconsistencies (not shown) are hypothesized to be the cause.Conclusion

We have proposed a quantitative scout (Q-SCOUT) to predict time-resolved navigator contrast for enhanced motion and B0-perturbation estimation (QUEEN). A rapid navigator was developed for this purpose and can be flexibly inserted in most sequences. Simulations show the potential of Q-SCOUT+QUEEN to achieve improved motion estimates, especially in the presence of B0-perturbations. This was confirmed in-vivo, although model imperfections limit the achieved accuracy. Future work will investigate these model imperfections and translate the proposed approach to in-vivo within-echo-train motion correction.Acknowledgements

This work was partly funded by the King’s College London & Imperial College London EPSRC Centre for Doctoral Training in Medical Imaging [EP/S022104/1].References

[1] Zaitsev M, Maclaren JR, Herbst M. “Motion artifacts in MRI: A complex problem with many partial solutions.” Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (2015): 42(4):887-901.

[2] van der Kouwe AJ, Benner T, Dale AM. “Real-time rigid body motion correction and shimming using cloverleaf navigators.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2006): 56(5):1019-32.

[3] Liu J, Drangova M. “Rapid six-degree-of-freedom motion detection using prerotated baseline spherical navigator echoes.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2011): 65(2):506-14.

[4] Kober T, Marques JP, Gruetter R, Krueger G. “Head motion detection using FID navigators.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2011): 66(1):135-43

[5] Wallace TE, Afacan O, Waszak M, Kober T, Warfield SK. “Head motion measurement and correction using FID navigators.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2019): 81(1):258-274.

[6] Wallace TE, Afacan O, Kober T, Warfield SK. “Rapid measurement and correction of spatiotemporal B0 field changes using FID navigators and a multi-channel reference image.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2020): 83(2):575-589.

[7] Polak D, Splitthoff DN, Clifford B, Lo W, TabariA, Lang A, Huang S, Conklin J, Wald LL, Cauley S. “Guidance lines for robust retrospective motion correction in 2D and 3D MRI.” In: Proc Int Soc Mag Reson Med Motion correction workshop (2022).

[8] Malik SJ, Keihaninejad S, Hammers A, Hajnal JV. “Tailored excitation in 3D with spiral nonselective (SPINS) RF pulses.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2012): 67(5):1303-15.

[9] Cao X, Liao C, Iyer SS, Wang Z, Zhou Z, Dai E, Liberman G, Dong Z, Gong T, He H, Zhong J, Bilgic B, Setsompop K. Optimized multi-axis spiral projection MR fingerprinting with subspace reconstruction for rapid whole-brain high-isotropic-resolution quantitative imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2022): 88(1):133-150.

[10] Dong Z, Wang F, Reese TG, Bilgic B, Setsompop K. Echo planar time-resolved imaging with subspace reconstruction and optimized spatiotemporal encoding. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2020):84(5):2442-2455.

[11] Van de Moortele PF, Pfeuffer J, Glover GH, Ugurbil K, Hu X. Respiration-induced B0 fluctuations and their spatial distribution in the human brain at 7 Tesla. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2002): 47(5):888-95.

[12] Lustig M, Kim SJ, Pauly JM. “A fast method for designing time-optimal gradient waveforms for arbitrary k-space trajectories.” IEEE Trans Med Imaging (2008): 27(6):866-73.

[13] Dietrich BE, Brunner DO, Wilm BJ, Barmet C, Gross S, Kasper L, Haeberlin M, Schmid T, Vannesjo SJ, Pruessmann KP. “A field camera for MR sequence monitoring and system analysis.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2016): 75(4):1831-40.

[14] Kim D, Cauley SF, Nayak KS, Leahy RM, Haldar JP. “Region-optimized virtual (ROVir) coils: Localization and/or suppression of spatial regions using sensor-domain beamforming.” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine (2021): 86(1):197-212.

Figures