0992

Active dictionary learning: fast and adaptive parameter mapping for dynamic MRI

Hongjun An1, Jiye Kim1, and Jongho Lee1

1Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, Republic of

1Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea, Republic of

Synopsis

Keywords: Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence, MR Fingerprinting

A new parameter mapping method, active dictionary learning, for dynamic MRI is proposed. This method trains a neural network adaptively by AI-guided MR signal simulation. For an MRF sequence with M0, T1, T2, B1, and ΔB0, our method successfully estimates the parameters much faster than conventional methods (ours: 30 min for whole process; dictionary methods: 6 hours for generation, 36 hours or 3 hours for matching). AI-guided active dictionary learning enables adaptive quantification of out-of-range parameters and efficient computation, suggesting the usefulness of the method not only in dynamic imaging but also in applications where adaptation to parameters is necessary.

Introduction

In quantitative MRI, parameters (e.g., T1, T2, B1, ΔB0, etc.) are typically estimated by dictionary matching1 or deep learning2-4. Both methods require a substantial time (~days; depending on # of parameters, range, resolution, etc) for the generation of precomputed MR signals from discretely dividing parameters either for the dictionary or network training, which may not be a big burden because it needs to be generated (and trained) once. In dynamic imaging (e.g., cardiac imaging using MRF with gating and sequence optimization), however, data for dictionary or network training may need to be regenerated for different scan parameters, hindering its applications.3 These dictionary generation or deep-learning training explores the whole search space and, therefore, has unnecessity, considering parameters under investigation often has limited variability. In this study, we propose a novel parameter mapping method with a highly reduced computation by using AI-guiding dictionary learning to search the expected target properties (Fig. 1).Methods

Active dictionary learning trains a neural network for parameter estimation by active dataset generation based on the target MR signals to reduce unnecessary simulation. The efficient training was performed using an active learning approach, which is learning a rough problem space with a few initial training data and then adaptively generating data for additional training.5 To explore potential parameters, a probabilistic network model was utilized, which was autoregressive flow.6[Active learning]

Our network was trained progressively by iterations of data recommendation and training (Fig. 2a). At first, the network is trained with a small size of a randomly generated dataset. After that, the inference was performed for a target signal, producing putative parameters as output. Then, these outputs were randomly sampled by using estimation quality from the autoregressive model for data recommendation. Finally, these sampled outputs were applied to the simulator to generate corresponding signals which were utilized for network training. As this process repeated, the estimation results became more accurate and the whole process worked as a coarse-to-fine search (Fig. 2b).

[Experiments]

For demonstration of the whole quantification process from dictionary generation stage, a FISP MRF sequence7 was used to estimate for M0, T1, T2, B1, and ΔB0. The MRF simulation was conducted with extended phase graph (EPG) with GPU acceleration.8

The target MR signals were generated by voxel-wise simulation using M0, T1, and T2 mapping results from in-vivo data. Additionally, gaussian-shaped B1 and horizontal-striped ΔB0 were assumed. MR signals were corrupted by Gaussian noise. The total size of the target data was 542,381 voxels with mean SNR of 7.

For comparison, dictionary matching results and computational time were calculated. The dictionary matching was performed in both cases using a full dictionary and a compressed dictionary by SVD compression9 to 100 values on different B1 values. The dictionary ranges were T1=[20:20:3000, 3000:200:5000] ms, T2=[10:5:300, 300:50:500, 500:200:2000] ms, B1=0.7:0.05:1.3, and ΔB0=-200:10:200 Hz, resulting in a total of 5,099,120 atoms.2,6,10

Experiment 1: For validation, the proposed method was tested for B1 and ΔB0 range from 0.7 to 1.2 and from -200 to 200 Hz, respectively.

Experiment 2: To demonstrate the adaptive estimation of the proposed method, the parameters were out of ranges from Experiment 1: B1 from 1.2 to 1.7 and ΔB0 from 0 to 400 Hz.

Experiment 3: A computationally expensive signal model with 64 points of a slice profile was evaluated. In this setting, dictionary generation using the model took over 1 month in our environment, therefore, the same dictionary with Experiments 1-2 was used.

For active dictionary learning, initial training data were randomly generated in the same ranges as the dictionary. The target signals were normalized to have standard deviations of 0.1. The number of initial data was 20,000, the additional dataset per iteration was 2,000, and the data addition process was repeated 20 times.

All experiments were conducted with i7-9800X CPU and an Nvidia TITAN Xp GPU.

Results

In Experiment 1 (Fig. 3), the proposed active dictionary learning showed successful estimation of the parameters using only 60,000 simulations. The performance was comparable to the full dictionary matching while taking only 30 min for the entire process (ours: 30 min for whole process; Full dictionary matching: 6 hours for generation and 36 hours for matching; SVD-compressed dictionary matching: 6.5 hours for generation and 3 hours for matching). In Experiment 2, out method demonstrated successful adaptation to the out-of-initial parameters range (Fig. 4). Experiment 3 also demonstrate successful estimations with much higher accuracy than the conventional method, while taking only 3 hours despite the need for simulating the slice profile (Fig. 5).Discussion and Conclusion

In this work, a novel parameter mapping method, active dictionary learning, is proposed for fast and adaptive mapping of parameters. This method may be valuable for dynamic imaging such as cardiac MRF, which changes the scan parameters for each subject, requiring dictionary generation for each case and, therefore, taking substantial computation and time when the conventional method is used. Additionally, our adaptation to out-of-range parameters indicates benefit in imaging targets of unknown or unexpected parameter ranges. Similar to the dictionary methods requiring only one time of generation, our method may be further improved or reused by pretraining the network to expected target range data, reducing the iteration time.Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korea government (MSIT) (No. NRF-2022R1A4A1030579 and No. NRF-2019M3C7A1031994).References

[1] Tropp, J. A., & Gilbert, A. C. (2007). Signal Recovery From Random Measurements Via Orthogonal Matching Pursuit. IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, 53(12), 4655–4666.

[2] Cohen, O., Zhu, B., & Rosen, M. S. (2018). MR fingerprinting Deep RecOnstruction NEtwork (DRONE). Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 80(3), 885–894.

[3] Hamilton, J. I., & Seiberlich, N. (2020). Machine Learning for Rapid Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting Tissue Property Quantification. Proceedings of the IEEE, 108(1), 69–85.

[4] Yang, M., Jiang, Y., Ma, D., Mehta, B. B., & Griswold, M. A. (2018). Game of Learning Bloch Equation Simulations for MR Fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. Abstract 0673.

[5] Papamakarios, G., Sterratt, D., & Murray, I. (2019). Sequential neural likelihood: Fast likelihood-free inference with autoregressive flows. In The 22nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (pp. 837-848). PMLR.

[6] Papamakarios, G., Pavlakou, T., & Murray, I. (2017). Masked autoregressive flow for density estimation. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30.

[7] Jiang, Y., Ma, D., Seiberlich, N., Gulani, V., & Griswold, M. A. (2015). MR fingerprinting using fast imaging with steady state precession (FISP) with spiral readout. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 74(6), 1621-1631.

[8] Wang, D., Ostenson, J., & Smith, D. S. (2020). snapMRF: GPU-accelerated magnetic resonance fingerprinting dictionary generation and matching using extended phase graphs. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 66, 248–256

[9] McGivney, D. F., Pierre, E., Ma, D., Jiang, Y., Saybasili, H., Gulani, V., & Griswold, M. A. (2014). SVD compression for magnetic resonance fingerprinting in the time domain. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 33(12), 2311–2322.

[10] Han, D., Hong, T., Lee, Y., & Kim, D. H. (2021). High Resolution 3D Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting with Hybrid Radial-Interleaved EPI Acquisition for Knee Cartilage T 1, T 2 Mapping. Investigative Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 25(3), 141-155.

[3] Hamilton, J. I., & Seiberlich, N. (2020). Machine Learning for Rapid Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting Tissue Property Quantification. Proceedings of the IEEE, 108(1), 69–85.

[4] Yang, M., Jiang, Y., Ma, D., Mehta, B. B., & Griswold, M. A. (2018). Game of Learning Bloch Equation Simulations for MR Fingerprinting. In Proceedings of the 26th Annual Meeting of the International Society for Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. Abstract 0673.

[5] Papamakarios, G., Sterratt, D., & Murray, I. (2019). Sequential neural likelihood: Fast likelihood-free inference with autoregressive flows. In The 22nd International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Statistics (pp. 837-848). PMLR.

[6] Papamakarios, G., Pavlakou, T., & Murray, I. (2017). Masked autoregressive flow for density estimation. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30.

[7] Jiang, Y., Ma, D., Seiberlich, N., Gulani, V., & Griswold, M. A. (2015). MR fingerprinting using fast imaging with steady state precession (FISP) with spiral readout. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 74(6), 1621-1631.

[8] Wang, D., Ostenson, J., & Smith, D. S. (2020). snapMRF: GPU-accelerated magnetic resonance fingerprinting dictionary generation and matching using extended phase graphs. Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 66, 248–256

[9] McGivney, D. F., Pierre, E., Ma, D., Jiang, Y., Saybasili, H., Gulani, V., & Griswold, M. A. (2014). SVD compression for magnetic resonance fingerprinting in the time domain. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 33(12), 2311–2322.

[10] Han, D., Hong, T., Lee, Y., & Kim, D. H. (2021). High Resolution 3D Magnetic Resonance Fingerprinting with Hybrid Radial-Interleaved EPI Acquisition for Knee Cartilage T 1, T 2 Mapping. Investigative Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 25(3), 141-155.

Figures

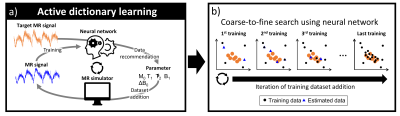

Figure 1. (a) Overview of the proposed method. Our method was

designed for fast and adaptive parameter mapping, which was referred to as active

dictionary learning. Different from the other methods, the proposed method is

based on AI-guided simulation to efficiently search the expected target parameter,

indicating a highly reduced computations and also adaption to out-of-range

parameters. (b) A scenario in dynamic imaging that changes scan parameters for

each subject. Our method may have benefits by highly reduced computations when

frequent dictionary generation is required.

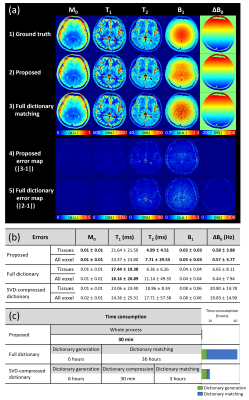

Figure 2. (a) A framework of active dictionary learning. The neural

network is trained progressively by utilizing adaptive data generation for

additional training. Instead of the searching all parameters, the neural

network recommends the parameters by using the target data after the training. Then,

these parameters are used to simulate MR signals for the next training dataset.

This process is repeated. (b) Estimation process along the repetition of training.

As a coarse-to-fine search, our method starts with coarse initial data and

becomes more accurate during the repetitions.

Figure

3. Results of Experiment 1. (a) The estimated parameters

using the proposed method and full dictionary matching. (b) The error of the

estimations from the proposed method and dictionary methods (full dictionary

matching and SVD-compressed dictionary matching). The proposed method yielded

comparable performance with the dictionary methods. (c) Time consumption of each

method. The proposed method archived a substantial reduction of time

consumption.

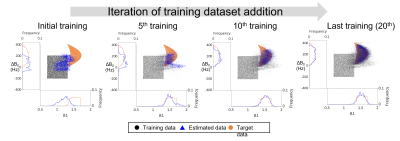

Figure 4. Results of Experiment 2. The proposed method demonstrated successful

adaptation to the out-of-initial parameters range while the dictionary methods failed.

Our method progressively generated the estimated data (blue) closer to the

target data (orange) while beginning with the initial training data (black)

during the repetitions.

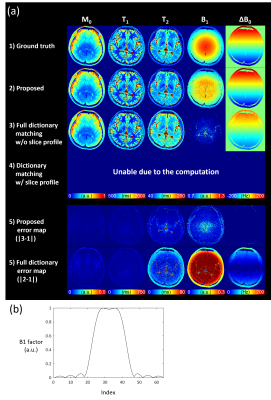

Figure

5. Results of Experiment 3. (a) Our method was applied

to the computationally expensive simulation model including the slice profile,

which makes the dictionary generation almost unable due to the computation,

resulting in the successful estimation. Dictionary matching without consideration

of slice profile induced high errors. (b) Slice profile that was used in this experiment.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0992