0977

Motion-compensated diffusion imaging with phase-contrast (MC-DIP) for the quantification of regional cerebral blood flow1Kanazawa University, Kanazawa, Japan, 2University of Miami, Miami, FL, United States, 3Philips Japan, Tokyo, Japan

Synopsis

Keywords: Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques

Diffusion imaging with phase-contrast (DIP) can quantitatively evaluate regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF), in which total CBF (tCBF) from phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (PC-MRI) converts the brain’s perfusion-related diffusion parameters into rCBF values. However, it is sensitive to bulk motion (i.e., brain pulsation), potentially causing an overestimation of DIP-derived rCBF values. To overcome this issue, we propose a motion-compensated DIP (MC-DIP) that incorporates motion-compensated diffusion gradients. DIP with second-order motion-compensated diffusion gradients (2nd-MC-DIP) improved the fitting accuracy of the biexponential analysis and showed the ability to quantitatively evaluate rCBF in gray and white matter.INTRODUCTION

The perfusion-related diffusion parameter in intravoxel incoherent motion analysis is closely associated with regional cerebral blood flow (rCBF).1,2 However, it is only a semiquantitative relative value of rCBF, making absolute rCBF quantification challenging. To overcome this issue, diffusion imaging with phase-contrast (DIP) was developed, in which total CBF (tCBF) from phase-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (PC-MRI) converts the brain’s perfusion-related diffusion parameters into rCBF values.3 However, it is sensitive to bulk motion (i.e., brain pulsation), which potentially causes artificial intravoxel phase dispersion and signal loss.4 This may cause overestimation of perfusion-related diffusion parameters and DIP-derived rCBF values. Therefore, we propose a motion-compensated DIP (MC-DIP) incorporating motion-compensated diffusion gradients to reduce the bulk motion effects on rCBF quantification.MATERIALS AND METHODS

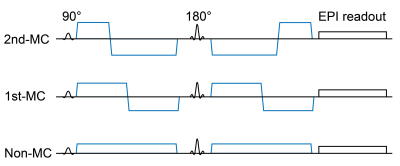

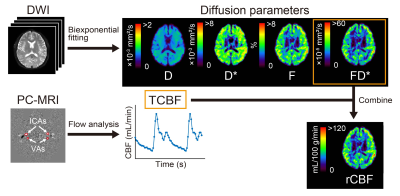

Nine males and two females (mean age, 23.9 years) were scanned on 3.0T MRI. Single-shot diffusion echo-planar imaging of the brain was performed with motion-uncompensated gradients (non-MC) and first- and second-order motion-compensated diffusion gradients (1st-MC and 2nd-MC, respectively; Figure 1). Transverse diffusion-weighted images of the whole brain were obtained with multiple b values (0, 10, 20, 30, 50, 100, 200, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 s/mm2). Voxel-wise estimations of the perfusion-related diffusion coefficient (D*), perfusion fraction (F), multiplication of D*and F (FD*), and restricted diffusion coefficient were conducted using bi-exponential function. Parameter estimation was performed by using a stepwise approach to improve the robustness of the analysis.2 The fitting procedure was performed using MATLAB with the Levenberg-Marquardt nonlinear least-squares algorithm. The normalized root-mean-square error (nRMSE) was calculated to evaluate the goodness-of-fit of the biexponential model for the measured data from each diffusion gradient scheme. A smaller nRMSE indicates a better fitting quality.PC-MRI with retrospective peripheral gating was performed to obtain the tCBF. The transverse imaging plane was set at the mid-C2 level perpendicular to the internal carotid arteries (ICAs) and vertebral arteries (VAs). We obtained velocity-mapped phase images, delineated the lumen boundaries of the ICAs and VAs on the phase images, and determined the volumetric flow rates within the lumen. Then, the tCBF was calculated as the sum of the volumetric flow rates of the four lumens (i.e., ICAs and VAs on both sides). Using tCBF, FD* values in the brain were converted into absolute rCBF in units of mL/100 g/min (Figure 2).

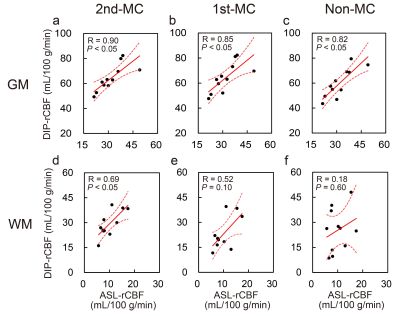

Reference rCBF values were obtained using three-dimensional gradient and spin-echo pulsed continuous arterial spin labeling (ASL). rCBF values obtained using ASL and DIP with 2nd-MC, 1st-MC, and non-MC were measured in gray and white matter (GM and WM, respectively). We evaluated the correlations between the DIP with each MC scheme and ASL using Spearman’s correlation coefficient, and compared the nRMSE between the MC methods using Friedman’s test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

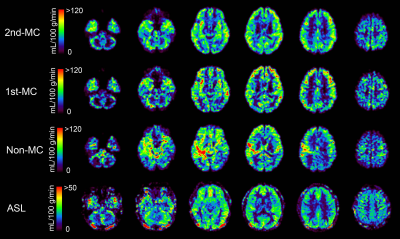

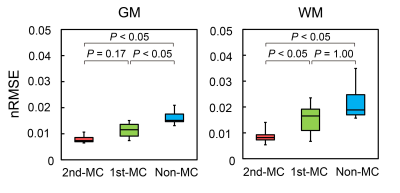

Figure 3 shows the representative rCBF images from the same subject obtained using each method. The rCBF images obtained with the 2nd-MC-DIP showed better GM-WM contrast and fewer artifacts than the 1st-MC- and non-MC-DIP images. The 2nd-MC-DIP had a significantly lower nRMSE in the WM than the 1st-MC- and non-MC-DIP (Figure 4). The nRMSE for the 2nd-MC-DIP was also significantly lower in the GM than that for the non-MC-DIP. These results indicate that 2nd-MC diffusion gradients can improve the fitting accuracy of the biexponential function by reducing the bulk motion effect more efficiently.5Figure 5 shows scatter plots of rCBF in GM and WM obtained using each DIP method and ASL. We observed significant positive correlations of rCBF in the GM between DIP with each MC method and ASL. Moreover, we found a significant positive correlation of rCBF in the WM between the 2nd-MC-DIP and ASL, indicating the ability of 2nd-MC-DIP to quantify rCBF values in the GM and WM. In contrast, there was no significant correlation between 1st-MC- or non-MC-DIP and ASL. This lack of correlation might be attributed to the lower fitting accuracy in the 1st-MC- and non-MC-DIP, as shown by the results of nRMSE in the WM.

CONCLUSION

The 2nd-MC-DIP reduced the bulk motion effect on the biexponential diffusion analysis and enabled the robust quantification of rCBF.Acknowledgements

This study was supported by JSPS KAKENHI (grant number 18KK0450 and 22K07794).References

1. Le Bihan D, Turner R. The capillary network: a link between IVIM and classical perfusion. Magn Reson Med. 1992; 27: 171-178.

2. Ohno N, Miyati T, Kobayashi S, Gabata T. Modified triexponential analysis of intravoxel incoherent motion for brain perfusion and diffusion. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2016; 43: 818-823.

3. Nunes RG, Jezzard P, Clare S. Investigations on the efficiency of cardiac-gated methods for the acquisition of diffusion-weighted images. J Magn Reson. 2005; 177: 102-110.

4. Ohno N, Miyati T, Sugita F, et al. Quantification of regional cerebral blood flow using diffusion imaging with phase contrast. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2021; 54: 1678-1686.

5. Stoeck CT, von Deuster C, Genet M, Atkinson D, Kozerke S. Second-order motion-compensated spin echo diffusion tensor imaging of the human heart. Magn Reson Med. 2016; 75: 1669-1676.

Figures