0973

Axon diameter mapping is confounded by glial cells1Center for Biomedical Imaging, Dept. Radiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Cardiff University Brain Research Imaging Centre (CUBRIC), Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom, 3School of Computer Science and Informatics, Cardiff University, Cardiff, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, Microstructure, Modeling, Axon Diameter Mapping

The specificity of strongly diffusion-weighted MRI to intra-axonal signal contributions to neuronal processes has always been presumed. Here we demonstrate empirically that strongly diffusion-weighted MRI data is also sensitive to a distinct isotropic compartment that may bias axon diameter estimates. We hypothesize that such a compartment represents isotropically-distributed glial processes. We use in vivo human data and Monte Carlo simulations to support our hypothesis and evaluate a novel strategy to suppress signal arising from glial cell bodies and processes to promote more accurate axon diameter mapping.Introduction

It has been suggested that strongly diffusion-weighted MRI (dMRI) signals in human white matter (WM) tracts come solely from within micrometer-thin axon [1]. Our ability to suppress the extra-axonal signal by using strong diffusion-weighting provided a pathway for axon diameter mapping. Indeed, at sufficiently high diffusion-weightings, the dMRI signal can be modeled as narrow cylinders with an effective radius that depends on the distribution of axon radii without any signal contributions from the extra-axonal space [2]. Signal contribution of glial processes has been suggested as a potential confounding factor for the accuracy of axon diameter mapping, but glial cells have received little to no attention in biophysical modeling of dMRI signals in WM [3-5]. Here, we revisit the widely-adopted assumption of axonal specificity by revisiting previous human experiments at the Connectom 3T scanner.Methods

Data: Five adult healthy subjects underwent two sessions of MRI scanning on the Siemens Connectom 3T scanner. During each session, a protocol consisting of two shells of b=[6000,30000]s/mm2 was acquired in 24 mins at a spatial resolution of 2.5x2.5x2.5mm3. After image preprocessing, we estimated the spherical harmonic coefficients up to the 6th order using a maximum likelihood estimator to create voxel-wise maps of the zeroth and second order rotational invariants. For details on the acquisition/preprocessing see [6]Model: The effective axon radius $$$r$$$ is typically estimated using the zeroth order rotation invariants (spherical mean, $$$\mathring{S}_\mu(b)$$$) of all $$$b\geq 6000\mathrm{s/mm2}$$$ using the following model: $$$\mathring{S}_\mu(b)=\beta \frac{S_c^\perp(r | q, \delta, \Delta)}{\sqrt{b}}$$$ with $$$q,\delta$$$ and $$$\Delta$$$ the diffusion-weighting wave vector, gradient duration, and gradient separation, respectively. Moreover, the $$$b$$$-value $$$b = q^2\delta^2\left(\Delta-\delta/3 \right)$$$. The radial signal attenuation $$$S_c^\perp(r | q, \delta, \Delta)$$$ is modeled using the Gaussian phase approximation of the signal from protons trapped inside a cylinder with radius $$$r$$$. The prefactor $$$\beta$$$ is a second model parameter related to both the intra-axonal signal fraction and intra-axonal axial diffusivity $$$D_a$$$, cf. [2].

Alternatively, the effective axon radius $$$r$$$ can be estimated using the second order rotational invariants (a proxy for the spherical variance; $$$\mathring{S}_\sigma(b)$$$)) as follows: $$$\mathring{S}_\sigma (b)=p_2\beta\left( 3- 2bD_a \right) \frac{S_c^\perp(r | q, \delta, \Delta)}{\sqrt{b^3}}$$$ with $$$q,\delta$$$. The prefactor $$$p_2$$$ represents a cellular projections alignment index [7].

Crucially, the estimation of the effective axon radius is expected to be independent of the order of the rotational variations - unless the high b signal has significant contributions from a distinct “isotropic compartment” in addition to the axonal compartment.

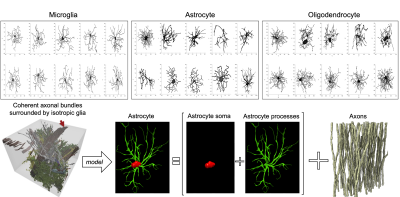

Monte Carlo simulations: We investigated the impact of a distinct “isotropic compartment” in addition to the axonal compartment using Monte Carlo simulations of spins diffusion within synthetic cellular substrates from real microscopy reconstructions. We reconstructed the three-dimensional surfaces of microglia, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes from the neuromorpho.org database. Realistic three-dimensional axonal reconstructions were extracted from electron microscopy data of the splenium of a monkey brain [8] (Fig.1). We generated synthetic diffusion-weighted MRI signals according to the experimental protocol of our MRI data [9], using 104 walkers uniformly distributed within each glial cell/axon, diffusivity 2.5 $$$\mathrm{mm^2/ms}$$$ and fixed-length off-lattice step 0.40 $$$\mu$$$m. We additionally used the matrix formalism for diffusion signal attenuation within fully restricted infinitely-long straight cylinders to model axonal signal [10]. We did not simulate the contribution of the extra-cellular compartment and assumed exchange is negligible at diffusion times ≤45ms [11].

Results

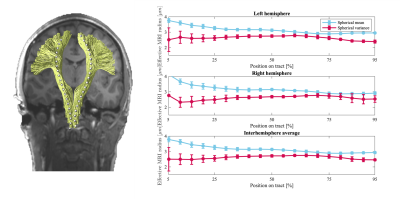

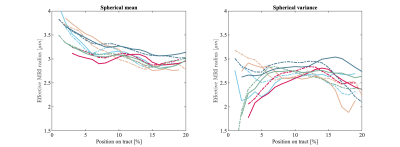

Fig.2 shows the trends of the effective axon radii along the cortico-spinal tract, averaged over the five subjects and two repetitions, for both hemispheres, and the interhemispheric average. Fig.3 also shows the trends for the individual subjects and repeated measurements. The agreement between test-retest and spherical mean and spherical variance in the estimation of the effective axon radius is evaluated using the intra-class correlation coefficient, ICC [12]. The test-retest agreement is good (ICC=0.77) and moderate (ICC=0.72) for the spherical mean and spherical variance, respectively. In contrast, the agreement between the spherical mean and spherical variance-derived metrics is poor (ICC=0.11)Fig.4 shows the effective axon radius estimated from simulated noise-free diffusion-weighted signals from a mixture of axons and glial cells as a function of their relative signal fraction.

Discussion

The disagreement between effective radii that are estimated using the spherical mean and variance suggests that an isotropic compartment is encoded in the high b signal - undermining the pending hypothesis that such signal is specific to axons. We here hypothesis that such signal arises from the complex cytoarchitecture of glial cells – especially the processes of astrocytes and oligodendrocytes. These glial cells are abundant in WM and are morphologically distinct from axons (Fig.1). We find support for our hypothesis in study-specific Monte Carlo simulations using mixture of axons and glial cells (see Fig.1 and 4). Unfortunately, in such simulations, postmortem axonal beading and undulations tend to impede axon diameter mapping, mainly when using the spherical mean [13,14].Conclusion

Empirical observations and Monte Carlo simulations suggest that diffusion MRI is sensitive to signal within glial cells and their processes and that such signals might lower their mesoscopic specificity and affect the interpretation of current modeling strategies, including axon diameter mapping. In addition, we here provide a novel avenue for the extraction and quantification of the intra-axonal signal in well-aligned fiber bundles by filtering out isotropic signal contributions.Acknowledgements

Funding: R01NS088040, P41EB017183, R01NS128190, UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship (MR/T020296/2). The data were acquired at the UK National Facility for In Vivo MR Imaging of Human Tissue Microstructure funded by the EPSRC (grant EP/M029778/1), and The Wolfson Foundation, and supported by a Wellcome Trust Investigator Award (096646/Z/11/Z) and a Wellcome Trust Strategic Award (104943/Z/14/Z)

References

[1] Veraart et al. (2019) NeuroImage 185: 379-387

[2] Veraart et al. eLife 9:e49855 (2020)

[3] Garcia-Hernandez et al. (2022 Science Advances 8.21: eabq2923.

[4] Benjamini et al. (2022) Brain.

[5] Raven et al . (2020) Research Square https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-80221/v1

[6] Veraart et al. (2021) Human Brain Mapping 42(7):2201-2213.

[7] Novikov et al. NeuroImage 174:518-538 (2018)

[8] Andersson et al. PNAS 117.52 (2020): 33649-33659.

[9] Hall and Alexander (2009) IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging, 28:1354-1364

[10] Ianuş et al. (2016) In International workshop on simulation and synthesis in medical imaging, page 34-44

[11] Yang et al. (2018) Magnetic resonance in medicine 79:1616-1627

[12] Koo and Li (2016) J Chiropr Med. 15(2): 155–163.

[13] Lee et al. (2020) NeuroImage 223:117228

[14] Lee et al. (2022) ISMRM workshop on Diffusion MRI proceedings, Amsterdam, abstract #56

Figures

Figure 1: realistic scenarios of coherent axonal bundles surrounded by isotropic glial cells, we used a computational model comprised of realistic glial cells (also distinguishing the relative contributions of soma and processes) and packed straight infinitely long cylindrical axons.

Figure 2 The average trend of the effective MR radi ($$$\mu m$$$) along the cortices-spinal tract (inferior to superior), computed using spherical mean and spherical variance are shown in blue and red, respectively. Each trend shows the average across 5 subjects and 2 repetitions. The error bars indicate the standard error (95% confidence interval) of the measurements. Such average trends are shown for both hemispheres, as well as the interhemisphere average.

Figure 3 The trends of the effective radii along the cortico-spinal tract are shown for each subject (solid) and repetition (dashed). The effective MRI radius was computed from the spherical mean (left) and spherical variance (right). The test-retest agreement of the measurements are moderate to good, but the agreement between the spherical mean and spherical variance estimates is poor.

Figure 4 [Monte Carlo simulations] The effective MRI radius is shown as a function of the Signal fraction of the glia for both the spherical mean (blue) and spherical variance (red). Axonal signals were simulated using (A) realistic axonal shapes and (B) straight cylinders.