0972

Zero-shell diffusion MRI: Focus on microstructure by decoupling fiber orientations1Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R), Department of Radiology, New York University School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, Data Acquisition

In brain dMRI, microstructure parameters of fiber fascicles, such as compartment fractions, exchange, diffusivities, relaxation rates, and structural disorder, are highly sought after. They can be accessed by sampling multiple diffusion weightings, b-tensor shapes, diffusion and/or echo times. Yet most scan time is spent oversampling the fiber orientation distribution function – because factoring it out nominally requires rotational invariants like the spherical mean. We show how to measure multiple inequivalent combinations of $$$(b,\,\Delta)$$$, while spending single gradient directions per unique combination. We recover signal’s rotational invariants for each one and use them for biophysical modeling of white and gray matter.Introduction

Using brain diffusion MRI (dMRI), we often aim to extract microstructure parameters of fiber fascicles (such as compartment fractions, diffusivities, relaxation rates, exchange between compartments, and structural disorder)1-6. These can be revealed by sampling different diffusion weightings, tensor shapes, diffusion and echo times. Yet most of our scan time is typically spent on oversampling the fiber orientation distribution function (fODF) – simply because factoring out the fODF nominally requires constructing spherical means7-8, or higher-order rotational invariants9,10.Here we show how to measure multiple combinations of experimental parameters – e.g. distinct combinations of diffusion weighting $$$b$$$ and diffusion time $$$\Delta$$$ – while spending only a single gradient direction $$$\hat{\mathbf{g}}$$$ per unique combination $$$(b,\,\Delta)$$$. In this way, we measure 550 distinct combinations of $$$(b,\,\Delta)$$$ in under one hour and recover their signal rotational invariants, which would have taken 30 hours if acquired instead for shells with 30 directions each. Finally, we apply our methods in vivo to observe the functional forms of fiber fascicles in both human white and gray matter, study diffusion time dependence, and use this data to estimate white and gray matter biophysical models.

Theory

The idea is to relate the singular value decomposition (SVD) of the signal from many voxels to the SVD of the (unknown) fiber fascicle response kernel, achieved using factorization in spherical harmonics (SH) space.SH Factorization: The voxelwise diffusion signal of many tissues, e.g. white and gray matter, can be modeled as a convolution over the sphere1,11-13:

$$S\left(b,\Delta,\hat{\mathbf{g}}\mid\!\,x,p_{\ell\,\!m}\right)=\int_{\mathbb{S}^{2}}d\hat{\mathbf{n}}\,\mathcal{K}(b,\Delta,\hat{\mathbf{g}}\cdot\hat{\mathbf{n}}\mid\,\!x)\,\mathcal{P}(\hat{\mathbf{n}}\mid\!\,p_{\ell\,\!m}),\quad(1)$$

where $$$b,\,\Delta,$$$ and $$$\hat{\mathbf{g}}$$$ define the measurement, $$$x=[f_a,D_a,T_{2,a},...,\tau_\mathrm{ex},...]$$$ contains the parameters describing the fiber response $$$\mathcal{K}$$$ (kernel), and $$$\mathcal{P}(\hat{\mathbf{n}}\mid\,\!p_{\ell\,\!m})=\sum_{\ell\,\!m}p_{\ell\,\!m}\,Y_{\ell\,\!m}(\hat{\mathbf{n}})$$$ is the fODF, represented by its spherical harmonics coefficients $$$p_{\ell\,\!m}$$$. Any spherical convolution can be replaced by a product in the SH basis:

$$S\left(b,\Delta,\hat{\mathbf{g}}\mid\,\!x,p_{\ell\,\!m}\right)=\sum_{\ell\,\!m}S_{\ell\,\!m}(b,\Delta)\,Y_{\ell\,\!m}(\hat{\mathbf{g}})=\sum_{\ell\,\!m}\mathcal{K}_{\ell}(b,\Delta\mid\!\,x)\,p_{\ell\,\!m}\,Y_{\ell\,\!m}(\hat{\mathbf{g}}).\quad(2)$$

where $$$\mathcal{K}_{\ell}$$$ are the kernel's rotational invariants.

SVD of kernel $$$\mapsto$$$ SVD of signal: While $$$\mathcal{K}_{\ell}$$$ are generally unknown, they admit the SVD factorization into protocol- and tissue-dependent components $$$u_n^{(\ell)}$$$ and $$$v_n^{(\ell)}$$$:

$$\mathcal{K}_\ell(b,\Delta\mid\,\!x)\simeq\sum_{n=1}^{N_{\ell}}s_{n}^{(\ell)}\,u_{n}^{(\ell)}(b,\Delta)\,v_{n}^{(\ell)}(x).\quad(3)$$

If we were to determine the components of Eq. (3) from a measurement, we could reconstruct the kernel $$$\mathcal{K}_{\ell}$$$. The way to measure $$$u_n^{(\ell)}$$$ and $$$v_n^{(\ell)}$$$ is to realize that, if we substitute Eq. (3) into Eq. (2), the signal

$$S\left(b,\Delta,\hat{\mathbf{g}}\mid\,\!x,p_{\ell\,\!m}\right)\simeq\sum_{n\ell\,\!m}s_{n}^{(\ell)}\,u_{n}^{(\ell)}(b,\Delta)\,Y_{\ell\,\!m}\left(\hat{\mathbf{g}}\right)\,v_{n}^{(\ell)}(x)\,p_{\ell\,\!m},\quad(4)$$

acquires an SVD form

$$S\left(b,\Delta,\hat{\mathbf{g}}\mid\!\,x,p_{\ell\,\!m}\right)\simeq\sum_{n^{\prime}}^NS_{n^{\prime}}\,U_{n^{\prime}}(b,\Delta,\hat{\mathbf{g}})\,V_{n^{\prime}}\left(x,p_{\ell\!\,m}\right),\quad(5)$$

where S is the diagonal matrix of singular values, and U and V depend solely on acquisition parameters and tissue, respectively. To ensure that $$$S_{n'}$$$ decay fast with $$$n'$$$, the signal SVD should be performed across voxels of the same tissue type, probing the same kernel across the range of values of its parameters $$$x$$$ and fODF components $$$p_{\ell\,\!m}$$$.

We now relate the components of Eq. (5) to those of Eq. (4) by assigning ``quantum numbers" $$$n,\,\ell,\,m$$$ to the columns of U, i.e. mapping $$$n'\rightarrow\{n,\ell,m\}$$$. This is done by projecting U on $$$Y_{\ell\,\!m}\left(\hat{\mathbf{g}}\right)$$$ and applying Wigner D-matrices to ``rotate'' U to the conventional SH basis. This results in the ``multiplets" (see Fig. 1b) with singular values $$$s_n^{(\ell)}$$$, ($$$2\ell+1$$$)-degenerate with respect to $$$m$$$, akin to atomic orbitals in the periodic table. We can then define protocol and tissue basis functions:

$$\alpha_{n\ell\,\!m}=u_{n}^{(\ell)}(b,\Delta)\,Y_{\ell\,\!m}\left(\hat{\mathbf{g}}\right),\quad\gamma_{n\ell\,\!m}=v_{n}^{(\ell)}(x)\,p_{\ell\,\!m},\quad(6)$$

where the $$$L_2$$$ norm over each ``multiplet" combined with sign estimation provides

$$\begin{aligned} \alpha_{n\ell}&=||\alpha_{n\ell\,\!m}||^{(m)}=\sqrt{\sum_{m}\alpha_{n\ell\,\!m}^{2}}=\sqrt{\tfrac{2\ell+1}{4\pi}}\,|u_{n}^{(\ell)}(b,\Delta)|,&&\tilde{\alpha}_{n\ell}=\alpha_{n\ell}\times\mathrm{sign}(u_{n}^{(\ell)}(b,\Delta)),\\\,\!\gamma_{n\ell}&=||\gamma_{n\ell\,\!m}||^{(m)}=\sqrt{\sum_{m}\gamma_{n\ell\,\!m}^{2}}=\sqrt{4\pi(2\ell+1)}\,p_{\ell}\,|v_{n}^{(\ell)}(x)|,&&\tilde{\gamma}_{n\ell}=\gamma_{n\ell}\times\mathrm{sign}(v_{n}^{(\ell)}(x)).\end{aligned}\quad(7)$$

These can be combined to recover the signal rotational invariants without knowing the kernel's functional form:

$$S_\ell\left(b,\Delta\mid\,\!x,p_{\ell}\right)=p_\ell\,\mathcal{K}_\ell(b,\Delta\mid\,\!x)=\tfrac{1}{2\ell+1}\,\sum_{n}\tilde{\alpha}_{n\ell}\,\tilde{\gamma}_{n\ell}.\quad(8)$$

Experiments

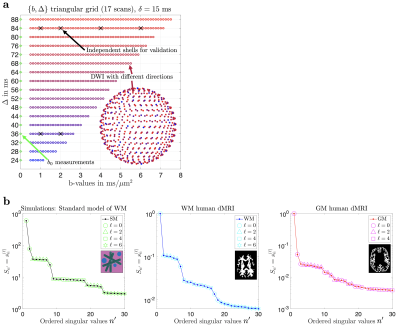

A 25-year-old male volunteer underwent 3T MRI (Siemens Magnetom Prisma) using a 32-channel head coil. A monopolar PGSE (Siemens WIP-511E) diffusion weighting sequence was used to acquire 550 diffusion-weighted images (DWIs) distributed into unique $$$(b,\,\Delta)$$$ pairs: $$$b\in[0,7.5]\,\mathrm{ms/\mu\,\!m^2},\,\Delta\in[24,88]\,\mathrm{ms}$$$, sampled in a triangular grid (see Fig. 1a), $$$\delta=15\,\mathrm{ms},\,t_\mathrm{acq}=55\,\mathrm{min}$$$. The 550 directions were uniformly distributed in the sphere and randomly assigned to each $$$(b,\,\Delta)$$$. For validation purposes, 6 complete shells were acquired at $$$(b\,[\mathrm{ms/\mu\,\!m^2}],\,\Delta\,[\mathrm{ms}],\,\mathrm{N}_\mathrm{dirs})=\{(1,36,24);(2,36,48);(1,84,24);(2,84,48);(4,84,48);(6,84,60)\},\,t_\mathrm{acq}=25\,\mathrm{min}$$$. Imaging parameters: voxel size$$$\,=2\times2\times2\,$$$mm$$$^3,\,\mathrm{TE}=120\,\mathrm{ms},\,\mathrm{TR}=5\,\mathrm{s},\,\mathrm{bandwidth}=2275\,\mathrm{Hz/Px},\,R_\mathrm{GRAPPA}=2,\,\text{partial Fourier}=6/8,\,\mathrm{Multiband}=2$$$.Results

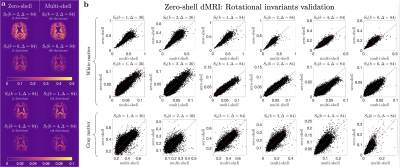

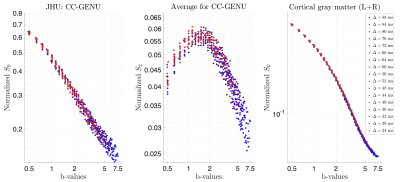

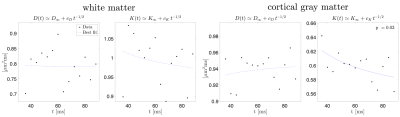

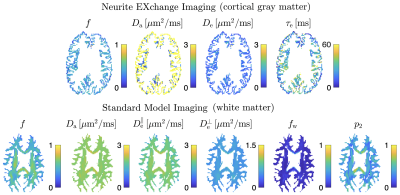

SVD of simulated voxels according to the Standard Model of diffusion in white matter, as well as measured human WM and GM, are shown in Fig. 1b. The presence of the multiplets of exactly $$$2\ell+1$$$ elements in the data supports the assumption of a convolution in the selected group of voxels. Furthermore, rotational invariants maps reconstructed using Eq. (8) for different WM/GM regions are shown in Fig. 2a, together with scatter plots showing high agreement with the validation shells. Their dependence on $$$b$$$ for WM/GM regions is shown in Fig. 3. We can use rotational invariants to compute DTI/DKI and study their time dependence (Fig. 4, in agreement with14), or to estimate any biophysical models like the Standard Model15 in WM or Neurite Exchange Imaging12 for GM (Fig. 5).Discussion and Conclusion

We measured in vivo brain dMRI signal rotational invariants in 550 unique $$$(b,\,\Delta)$$$ combinations without sampling complete shells on each of them. Our framework is built upon the convolution of the kernel and fODF but no assumptions are made about the functional form of the tissue response function which is allowed to vary between voxels. This method, readily extendable for B-tensor shapes, TE, etc, provides massive time savings for techniques requiring dense sampling of the multi-dimensional MRI acquisition space15-19. The number of distinct $$$s_n^{(\ell)}$$$ above the noise floor provides an upper limit to the number of degrees of freedom needed to model the kernel.Acknowledgements

This work has been supported by NIH under NINDS award R01 NS088040 and NIBIB awards R01 EB027075 and P41 EB017183. The authors are grateful to Sune N. Jespersen for fruitful discussions and to Thorsten Feiweier for providing the WIP-511E sequence.References

[1] D. S. Novikov, E. Fieremans, S. N. Jespersen, and V. G. Kiselev, “Quantifying brain microstructure with diffusion MRI: Theory and parameter estimation,” NMR in Biomedicine, p. e3998, 2019.

[2] C. D. Kroenke, J. J. Ackerman, and D. A. Yablonskiy, “On the nature of the naa diffusion attenuated MR signal in the central nervous system,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 52, no. 5, pp. 1052–1059, 2004.

[3] S. N. Jespersen, C. D. Kroenke, L. Østergaard, J. J. H. Ackerman, and D. A. Yablonskiy, “Modeling dendrite density from magnetic resonance diffusion measurements,” NeuroImage, vol. 34, pp. 1473–1486, 2007.

[4] E. Fieremans, J. H. Jensen, J. A. H. ans Sungheon Kim, R. I. Grossman, M. Inglese, and D. S. Novikov, “Diffusiondistinguishes between axonal loss and demyelination in brain white matter,” in Proceedings of the International Society of Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, Wiley, 2012.

[5] H. Zhang, T. Schneider, C. A. Wheeler-Kingshott, and D. C. Alexander, “NODDI: Practical in vivo neurite orientation dispersion and density imaging of the human brain,” NeuroImage, vol. 61, pp. 1000–1016, 2012.

[6] J. H. Jensen, G. Russell Glenn, and J. A. Helpern, “Fiber ball imaging,” NeuroImage, vol. 124, pp. 824–833, 2016.

[7] S. N. Jespersen, H. Lundell, C. K. Sønderby, and T. B. Dyrby, “Orientationally invariant metrics of apparent compartment eccentricity from double pulsed field gradient diffusion experiments,” NMR in Biomedicine, vol. 26, pp. 1647–1662, 2013.

[8] E. Kaden, N. D. Kelm, R. P. Carson, M. D. Does, and D. C. Alexander, “Multi-compartment microscopic diffusion imaging,” NeuroImage, vol. 139, pp. 346–359, 2016.

[9] M. Reisert, E. Kellner, B. Dhital, J. Hennig, and V. G. Kiselev, “Disentangling micro from mesostructure by diffusion MRI: A Bayesian approach,” NeuroImage, vol. 147, pp. 964 – 975, 2017.

[10] D. S. Novikov, J. Veraart, I. O. Jelescu, and E. Fieremans, “Rotationally-invariant mapping of scalar and orientational metrics of neuronal microstructure with diffusion MRI,” NeuroImage, vol. 174, pp. 518 – 538, 2018.

[11] J. D. Tournier, F. Calamante, D. G. Gadian, and A. Connelly, “Direct estimation of the fiber orientation density function from diffusion-weighted MRI data using spherical deconvolution,” NeuroImage, vol. 23, pp. 1176–1185,2004.

[12] I. O. Jelescu, A. de Skowronski, F. Geffroy, M. Palombo, and D. S. Novikov, “Neurite exchange imaging (NEXI): A minimal model of diffusion in gray matter with inter-compartment water exchange,” NeuroImage, vol. 256,p. 119277, 2022.

[13] J. L. Olesen, L. Østergaard, N. Shemesh, and S. N. Jespersen, “Diffusion time dependence, power-law scaling, and exchange in gray matter,” NeuroImage, vol. 251, p. 118976, 2022.

[14] H.-H. Lee, A. Papaioannou, D. S. Novikov, and E. Fieremans, “In vivo observation and biophysical interpretation of time-dependent diffusion in human cortical gray matter,” NeuroImage, vol. 222, p. 117054, 2020.

[15] S. Coelho, S. H. Baete, G. Lemberskiy, B. Ades-Aron, G. Barrol, J. Veraart, D. S. Novikov, and E. Fieremans, “Reproducibility of the Standard Model of diffusion in white matter on clinical MRI systems,” NeuroImage, vol. 257, p. 119290, 2022.

[16] J. Veraart, D. S. Novikov, and E. Fieremans, “TE dependent Diffusion Imaging (TEdDI) distinguishes between compartmental T2 relaxation times,” NeuroImage, vol. 182, pp. 360–369, 2018.

[17] B. Lampinen, F. Szczepankiewicz, J. M ̊artensson, D. van Westen, O. Hansson, C.-F. Westin, and M. Nilsson, “Towards unconstrained compartment modeling in white matter using diffusion-relaxation MRI with tensor-valued diffusion encoding,” Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 84, no. 3, pp. 1605–1623, 2020.

[18] J. Martin, A. Reymbaut, M. Schmidt, A. Doerfler, M. Uder, F. B. Laun, and D. Topgaard, “NonparametricD-R1-R2 distribution MRI of the living human brain,” NeuroImage, vol. 245, p. 118753, 2021.

[19] D. Benjamini, D. Iacono, M. E. Komlosh, D. P. Perl, D. L. Brody, and P. J. Basser, “Diffuse axonal injury has a characteristic multidimensional MRI signature in the human brain,” Brain, vol. 144, no. 3, pp. 800–816, 2021.

Figures