0959

Diffusion-weighted signals and intrinsic optical signal share a similar contrast mechanism

Nathan Hu Williamson1, Rea Ravin1,2, Teddy Xuke Cai1,3, and Peter Joel Basser1

1NICHD, NIH, Potomac, MD, United States, 2Celoptics, Rockville, MD, United States, 3Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

1NICHD, NIH, Potomac, MD, United States, 2Celoptics, Rockville, MD, United States, 3Wellcome Centre for Integrative Neuroimaging, Oxford, Oxford, United Kingdom

Synopsis

Keywords: Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques, Neuroscience, Microstructure

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) and intrinsic optical signal (IOS) are both used to measure neural tissue structure and function. Here we demonstrate with simultaneous real-time low-field, high-gradient MR and optical microscopy that DW signals and IOS share a similar contrast mechanism, most likely the ratio between intracellular and extracellular volume. Signals monitor how cells are affected and respond to adverse conditions, providing novel insight into pathological mechanisms and links between structure and function.Introduction

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) contrast measures water self-diffusion, which is sensitive to hindrances and restrictions by lipid membranes.1,2 In tissue, DW signal intensity is linked to changes in intracellular volume3, increasing with restricted volume as cells swell. However, the heterogeneity of restriction length scales, as well as the heterogeneity of exchange rates makes the DW signal difficult to model4 and interpret5. Moreover, studies show conflicting evidence for connections between DW signals and cellular function6,7.The origin of the IOS is light scattering from biomacromolecules and lipid membranes.8 In tissue, changes in light scattering are linked to changes in the extracellular volume. The IOS decreases as cells swell and extracellular space shrinks. However, simultaneous IOS and diffusion of extracellular tetramethyl ammonium (TMA) revealed at least one other unexplained mechanism.9,10 Some authors have suggested the complementary nature of IOS and diffusion MR for understanding contrast mechanisms linked to brain function.11,12

With a tandem low-field, high-gradient single-sided NMR profiler and light microscope one can image a sample while acquiring MR data.13 Here, simultaneous DW MR and IOS data are acquired on neural tissue with various perturbations and show concordant time series, revealing for the first time, we believe, a common contrast mechanism.

Methods

MR and optical microscopy measurements were acquired in real-time during perturbations to ex vivo neonatal mouse spinal cords2. MR measurements were performed at 13.79 MHz with a low-field, high-gradient, single-sided MR system (PM-10 NMR MOUSE, Magritek)14. Diffusion weighting is achieved by acquiring spin echoes (SE) in the presence of a g=15.3 T/m static gradient. Sub-millisecond diffusion encoding is obtained by rapidly switching the direction of the effective gradient using hard (2μs) radiofrequency (RF) pulses. SE signals were acquired using the standard diffusion sequence15 with τ (1/2 TE) =0.646 ms (b=3 ms/μm2), and 4 scans per signal. Diffusion exchange spectroscopy (DEXSY) signals were acquired using the DEXSY sequence2 with τ1=0.653 ms, τ2=0.639 ms, (bs= b2+b1 = 6 ms/μm2, bd=b2-b1 = 0.195 ms/μm2)16, mixing time tm=10 ms, and 8 scans per signal. For both measurements, TR=0.7 s, and a Carr–Purcell–Meiboom–Gill (CPMG) acquisition with 8000 echoes and TE=25 ms was summed together for each signal point. While both the SE and DEXSY signals are highly diffusion (and relaxation)-weighted, the DEXSY signal is also exchange-weighted16,17 and restriction-weighted18.A wide-field inverted microscope (Axiovert 200 M Zeiss) was used with 680 nm transmitted light illuminating the sample at 90° to the objective. The IOS was calculated from a region of interest (ROI) from images acquired every 5 seconds.

Results and Discussion

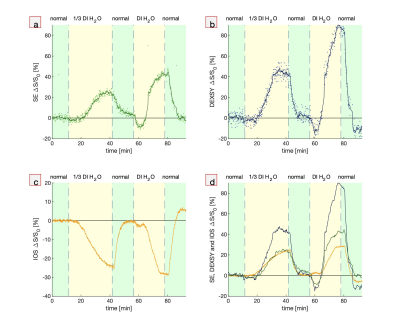

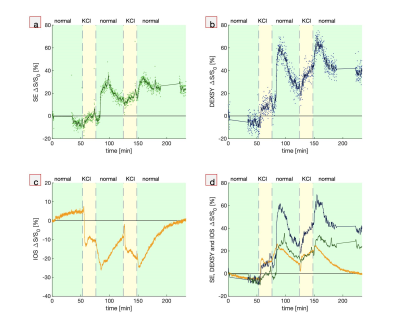

First, hypotonic perturbations are shown to confirm the sensitivity to cellular swelling (Fig. 1). The sample was perturbed from normal artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) to aCSF diluted with 1/3 part deionized (DI) water and then entirely to DI water. As expected, the DW MR signals go up and the IOS goes down. Signals recover when washing back to normal media, although there is some overshoot when washing back from entirely DI water, perhaps due to cell lysing.Second, perturbations involving the addition of large, 50 mM doses of KCl show DW signal and IOS changes consistent with cellular swelling. The addition of K+ increases activity of neurons and causes them to swell. Astrocytes swell as they take up K+ to buffer the extracellular K+ concentration.10 Interestingly, when washing back to normal aCSF, the signals diverge further from baseline and recover on a long (>1 hr) timescale. This could be an osmotic effect combined with the physiological role of astrocytes. Astrocytes may be swelling in response to washing with normal aCSF because of the sudden intracellular–extracellular osmolarity difference. Perhaps astrocytes are limiting the rate of K+ leakage because unregulated ion efflux could induce neuronal activity and excitotoxicity. At the end of the final wash, the signals diverge, and the IOS returns to baseline while the DW signals do not, indicating some underlying differences in sensitivity to microstructural changes. This data may indicate that the measurements are sensitive to astrocytic swelling, as has been suggested for DWI19 and IOS10.

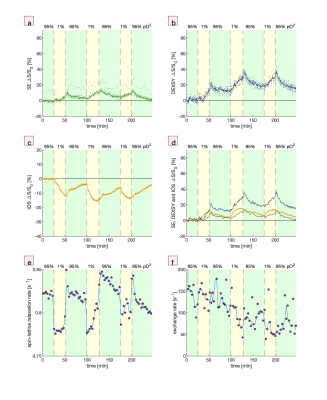

Third, hypoxic perturbations are presented (Fig. 3). When the aCSF is switched from being bubbled with gas containing 95% O2 (normal) to 1% O2 (hypoxic), the DW signals rise and the IOS falls. The signals recover when switching back to 95% O2, although not completely, consistent with some loss of viability of the cells as measured simultaneously by the exchange rate20.

Conclusion

DW signals and IOS track each other under a variety of perturbations known to induce cellular swelling and thus share a similar contrast mechanism. Given the sensitivity of DW signals to intracellular water and IOS to extracellular water, they are both most likely linked through the intracellular and extracellular volume fractions. The perturbations used here are extreme and would only be encountered under pathological (as opposed to normal physiological) conditions. It is therefore not possible to comment on the sensitivity of DW signals or IOS to normal cellular “function” in the most common use of the term. However, signal responses suggest that cells are working to maintain homeostasis under adverse conditions. The capability to monitor these responses in real-time will provide novel insight into pathological mechanisms and links between structure and function.Acknowledgements

All authors were supported by the IRP of the NICHD, NIH.

References

- J. Tanner, "Self diffusion of water in frog muscle," Biophysical journal, vol. 28, no. 1, pp. 107-116, 1979.

- N. H. Williamson et al., "Magnetic resonance measurements of cellular and sub-cellular membrane structures in live and fixed neural tissue," Elife, vol. 8, p. e51101, 2019.

- H. Benveniste, L. W. Hedlund, and G. A. Johnson, "Mechanism of detection of acute cerebral ischemia in rats by diffusion-weighted magnetic resonance microscopy," Stroke, vol. 23, no. 5, pp. 746-754, 1992.

- I. O. Jelescu, M. Palombo, F. Bagnato, and K. G. Schilling, "Challenges for biophysical modeling of microstructure," Journal of Neuroscience Methods, vol. 344, p. 108861, 2020.

- J. V. Sehy, J. J. Ackerman, and J. J. Neil, "Evidence that both fast and slow water ADC components arise from intracellular space," Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, vol. 48, no. 5, pp. 765-770, 2002.

- A. Darquié, J.-B. Poline, C. Poupon, H. Saint-Jalmes, and D. Le Bihan, "Transient decrease in water diffusion observed in human occipital cortex during visual stimulation," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 98, no. 16, pp. 9391-9395, 2001.

- R. Bai, C. V. Stewart, D. Plenz, and P. J. Basser, "Assessing the sensitivity of diffusion MRI to detect neuronal activity directly," Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 113, no. 12, pp. E1728-E1737, 2016.

- P. Aitken, D. Fayuk, G. Somjen, and D. Turner, "Use of intrinsic optical signals to monitor physiological changes in brain tissue slices," Methods, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 91-103, 1999.

- D. Fayuk, P. G. Aitken, G. G. Somjen, and D. A. Turner, "Two different mechanisms underlie reversible, intrinsic optical signals in rat hippocampal slices," Journal of Neurophysiology, vol. 87, no. 4, pp. 1924-1937, 2002.

- E. Syková, L. ýdia Vargová, S. Kubinová, P. Jendelová, and A. Chvátal, "The relationship between changes in intrinsic optical signals and cell swelling in rat spinal cord slices," Neuroimage, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 214-230, 2003.

- D. Nunes, R. Gil, and N. Shemesh, "A rapid-onset diffusion functional MRI signal reflects neuromorphological coupling dynamics," Neuroimage, vol. 231, p. 117862, 2021.

- R. Vincis, S. Lagier, D. Van De Ville, I. Rodriguez, and A. Carleton, "Sensory-evoked intrinsic imaging signals in the olfactory bulb are independent of neurovascular coupling," Cell reports, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 313-325, 2015.

- R. Bai et al., "Simultaneous calcium fluorescence imaging and MR of ex vivo organotypic cortical cultures: a new test bed for functional MRI," NMR in Biomedicine, vol. 28, no. 12, pp. 1726-1738, 2015.

- G. Eidmann, R. Savelsberg, P. Blümler, and B. Blümich, "The NMR MOUSE, a mobile universal surface explorer," Journal of Magnetic Resonance, vol. 122, no. 1, pp. 104-109, 1996.

- D. Rata, F. Casanova, J. Perlo, D. Demco, and B. Blümich, "Self-diffusion measurements by a mobile single-sided NMR sensor with improved magnetic field gradient," Journal of Magnetic Resonance, vol. 180, no. 2, pp. 229-235, 2006.

- T. X. Cai, D. Benjamini, M. E. Komlosh, P. J. Basser, and N. H. Williamson, "Rapid detection of the presence of diffusion exchange," Journal of Magnetic Resonance, vol. 297, pp. 17-22, 2018.

- N. H. Williamson et al., "Real-time measurement of diffusion exchange rate in biological tissue," Journal of Magnetic Resonance, vol. 317, p. 106782, 2020.

- T. X. Cai, N. H. Williamson, R. Ravin, and P. J. Basser, "Disentangling the Effects of Restriction and Exchange With Diffusion Exchange Spectroscopy," Frontiers in Physics, p. 223, 2022.

- S. J. Blackband et al., "On the Origins of Diffusion MRI Signal Changes in Stroke," Frontiers in Neurology, vol. 11, 2020.

- N. H. Williamson, R. Ravin, T. Cai, M. Falgairolle, M. O'Donovan, and P. Basser, "Water exchange rates measure active transport and homeostasis in neural tissue," bioRxiv, 2022.

Figures

Fig. 1. Simultaneous real-time NMR

and IOS during hypotonic perturbations. Real-time measurements while the

media is perturbed from normal aCSF to aCSF diluted with 1/3 part deionized

(DI) water and entirely DI water showing (a,b) MR SE and DEXSY signals (dots) and running

averages (lines), (c) IOS, and (d) running averages of MR SE and DEXSY signals plotted

with inverted (multiplied by -1) IOS, using the same colors as from a, b and c.

Signals are presented as percentage changes from the baseline,

ΔS/S0.

Fig. 2. Simultaneous real-time NMR

and IOS show similar and complementary behavior. Real-time measurements during

two perturbations from normal aCSF to aCSF + 50 mM KCl and back to normal showing (a,b) MR SE and DEXSY signals (dots) and running

averages (lines), (c) IOS, and (d) running averages of MR SE and DEXSY signals plotted

with inverted IOS. Gaps in the NMR data at the start and end of the experiment

show when the standard exchange rate and diffusion measurements were performed

for quality control.

Fig. 3. Simultaneous MR and

microscopy during bouts of hypoxia (1% pO2). (a) SE, (b) DEXSY, (c)

IOS (b) SE and DEXSY signals compared with inverted IOS, (d) spin-lattice relaxation

rates which monitor pO2, and (f) exchange rates which monitor tissue

viability20. Spin-lattice relaxation and exchange rate measurements

were repeated after every 10 points of SE and DEXSY. These measurements altered

the steady-state magnetization and imparted a systematic deviation in the SE

signal.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0959