0954

MRF-mixer: a self-supervised deep learning MRF framework1Central South University, Changsha, China, 2The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

Synopsis

Keywords: Contrast Mechanisms, MR Fingerprinting, relaxometry reconstruction, B0 estimation, self-supervised deep learning

Deep neural networks are increasingly employed in MRF reconstruction recently, as an alternative for conventional dictionary matching. However, most previous deep leanring MRF networks were trained based on the dictionary pairs (generated using theoretical bloch equation) or in vivo acquisitions paired with dictionary matching reconstructions (as training labels), whose reconstruction accuracy relies heavily on the dictionary construction and the number of sampling arms. In this work, we propose a self-supversied deep learning MRF method, namely MRF-Mixer, which can result in more accurate MRF reconstructions compared with dictionary matching.Introduction

MR fingerprinting (MRF)1-4 is a quantitative imaging modality which can extract multiple tissue parameters, such as T1 and T2, from a single scan, showing great potential for clinical applications. Traditioanl MRF reconstruction is accomplished with dictionary or template matching (DM)1-4, which maps the acquired in vivo signal to a predefined dictionary entry. Recently, deep learning have been proposed, such as MLP-based DRONE5 and CNN-based SCQ-Net6, which led to superior reconstruction performances over DM on T1 and T2 mapping. However, these CNN methods were trained with highly undersampled MRF data as inputs and traditional DM reconstruction results as labels, which may compromise the accuracy of the trained networks. This study proposed a self-supervised deep learning method, named as MRF-Mixer, to reconstruct T1, T2, and B0 images from the original IR-bSSFP MRF acquisition. In addition, simulation and in vivo experiments were conducted to compare the proposed MRF-Mixer with traditional DM.Methods

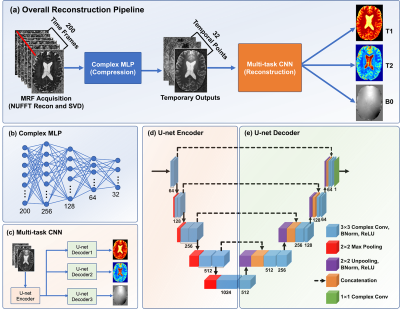

MRF-MixerThe proposed MRF-Mixer, as shown in Fig. 1(a), consists of two cascaded complex-valued networks. The first part (Fig. 1(b)) is a complex-valued multi-layer perceptron (MLP), which operates voxel-wisely on the temporal dimension of the input MRF data reconstructed from highly subsampled radial k-space (1, 3, and 6 radial spokes each TR). The complex MLP projected MRF input data onto a subspace of 32 dimensions (channel number), which is then fed into a multi-branch U-net (Fig. 1(c)), i.e., the second part of the MRF-Mixer. The multi-task U-net comprises one shared U-net encoder (Fig. 1(d)) and three different U-net decoders (Fig. 1(e)) for T1, T2, and B0, respectively.

Training data preparation

Sk = U*F*Bloch(T1, T2, B0; FAs, TRs), (1)

where Sk represents the simulated MRF signal evolution (in kspace), while T1, T2, and B0 images are employed as training labels. represents the singal evolution process taking the acquisition parameters (FAs (flip angles) and TRs (repetition times)) and tissue properties as inputs, while U and F are kspace undersampling matrix and Fourier Transform, respectively. In this work, the original IR-bSSFP sequence contains 1000 psudo-random FA and TR selections, which means that MRF image reconstruction from is of 1000 temporal frames. To improve the network performances, we further performed a singular value decomposition to compress the original data into images series of 200 time points, as shown in Fig. 1(a) and the top of Fig. 2 (red arrow).

To obtain realistic training labels (i.e., T1, T2, and B0 images), 10 healthy volunteers were scanned using MP2RAGE sequence. Then, we conduceted T1 mapping, T2* mapping, and QSM reconstruction on the MP2RAGE scans to extract T1, T2*, and B0 (total field) images. In this work, the T2* images multiplied by 1.5 were considered as T2 labels for network training.

Network training

A total of 2000 images (image size: 192x192) were simulated from 10 MP2RAGE brian sujects, and then randomly cropped into 24000 image patches (64x64) for network training. All network parameters were initialized with normally distributed random numbers of 0 mean and 0.01 standard deviation. The network was optimized with Adam optimizer with MSE loss for 100 epochs on two Nvidia Tesla V100 GPU. The batch size was 30, and the learning rate was initially set as 10-3, decaying by half every 15 epochs.

Validation on simulated and in vivo datasets

The proposed MRF-Mixer were compared with traditional DM method on a simulated data (IR-bSSFP sequence with only 1 radial sampling spoke) and three in vivo MRF scans (1, 3, and 6 radial sampling arms, respectively) from a healty volunteer at 3T with 1 mm isotropic resolution. The dictionary was simulated using the Bloch equation simulator, containing 643200 MRF dictionary pairs (T1 range: 100-4000 ms, with 100 ms step, T2 range: 10-800 ms with 10 ms step, and B0 range: -200-200 Hz, with 2 Hz step).

Results

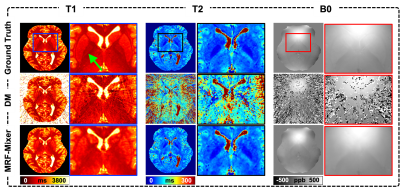

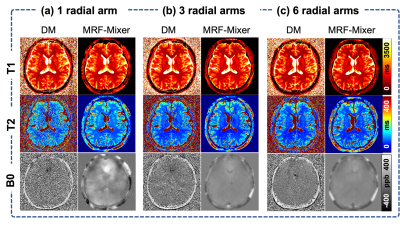

Comparison of MRF-Mixer and DM on the simulation data were shown in Fig. 3. MRF-Mixer always present better reconstructions than DM method, especially for T2 and B0 images, where DM method showed overwhelming artifacts. As pointed by the green arrow, although both methods failed to result in a “perfect” reconstruction for T1 in left putamen-globus pallidus region, MRF-Mixer exhibited better reconstructions for putamen region.Figure 4 compares the reconstruction results of MRF-Mixer and DM method on three in vivo MRF scans. MRF-Mixer resulted in more desirable T2 images, while DM demonstrated overwhelming artifacts, especially for 1-radial spoke sampling case. Although T1 and T2 results became better when the data is sampled with more radial arms (from 1 to 6), both methods seemed to failed accurate B0 reconstructions.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study proposed a deep learning-based reconstruction method to extract T1, T2, B0, images from the IR-bSSFP-MRF acquisition. Simulated and in vivo results showed that the proposed outperformed the traditional DM method; however, more comparisons with state-of-the-art methods are needed in the future.Acknowledgements

HS received funding from Australian Research Council (DE210101297).References

[1] Ma, Dan, et al. "Magnetic resonance fingerprinting." Nature 495.7440 (2013): 187-192.

[2] Ma, Dan. "MR fingerprinting: concepts, implementation and applications." Advances in Magnetic Resonance Technology and Applications 4 (2021): 435-449.

[3] Cloos, Martijn A., et al. "Multiparametric imaging with heterogeneous radiofrequency fields." Nature communications 7.1 (2016): 1-10.

[4] Cloos, Martijn A., et al. "Rapid radial T1 and T2 mapping of the hip articular cartilage with magnetic resonance fingerprinting." Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging 50.3 (2019): 810-815.

[5] Cohen, Ouri, Bo Zhu, and Matthew S. Rosen. "MR fingerprinting deep reconstruction network (DRONE)." Magnetic resonance in medicine 80.3 (2018): 885-894.

[6] Fang, Zhenghan, et al. "Deep learning for fast and spatially constrained tissue quantification from highly accelerated data in magnetic resonance fingerprinting." IEEE transactions on medical imaging 38.10 (2019): 2364-2374.

Figures