0930

2.5D Flow MRI: 2D phase-contrast of the tricuspid valvular flow with automated valve-tracking1Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States, 2National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States, 3Oxford University, Oxford, United Kingdom, 4Internal Medicine, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States, 5Lund University, Lund, Sweden

Synopsis

Keywords: Flow, Data Acquisition

Tricuspid regurgitant velocity is a crucial biomarker in identifying pressure overload in the right heart, associated with diastolic dysfunction and pulmonary hypertension. 2D phase-contrast cannot quantify this flow, and echocardiography is used clinically. We developed a phase-contrast method which utilizes deep-learning algorithms to track the valvular slice in a cardiac phase-dependent manner, which we call 2.5D flow. We studied its performance in nine healthy subjects and patients with tricuspid regurgitation. RV stroke volumes correlated better to forward flow volumes by 2.5D flow vs. static 2D phase-contrast (ICC=0.88 vs. 0.62). 2.5D flow characterized regurgitation in a patient.Introduction

Valve diseases are an important cause of morbidity and mortality (1). Specifically, tricuspid valve (TV) regurgitation can be detected in 80% of the general population and considered pathological (moderate or severe) in 15% (2). Tricuspid valvular regurgitation is often due to elevated right ventricle (RV) pressure, commonly seen in pulmonary hypertension (PH) (3) and patients with diastolic dysfunction, where tricuspid regurgitant velocity is one of 4 criteria used to identify dysfunction (along with LA volume, E/e’ and E/A) (4). Thus, evaluation of tricuspid regurgitant velocity is clinically highly important. A recent study (5) of diastolic dysfunction by MRI, used vorticity duration as a stand-in for tricuspid regurgitant flow, highlighting the need for its evaluation. According to the current ACC/AHA guidelines, TV regurgitation is assessed with a comprehensive transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) imaging with Doppler interrogation (1) of blood velocities. Cardiac MR is considered more accurate for mitral and tricuspid regurgitant volumes, using indirect evaluation by subtraction of RV (or LV) stroke volume (SV) from pulmonary artery (PA) or Aortic (Ao) forward flow (6,7). However, direct valve flow evaluation by cardiac MRI is not feasible due to valvular displacement during the cardiac cycle; even more so for the highly dynamic (translating and rotating) TV (8). 4D flow methods have had success in tricuspid regurgitant velocity evaluation, using many minutes of scan time, because retrospective valve tracking can be employed (9,10). Prospective valve-tracking methods have been employed to acquire 2D phase-contrast (PC) with a dynamic slice plane prescription that changes over the cardiac cycle (11,12). We recently used this approach, but using modern feature-tracking of the mitral valve (13) to enable rapid and accurate valve-tracking of the simple mitral valve translations (14). Even so, to obtain accurate displacements and valvular velocities (needed to correct flow values) often required expert, tedious, and time-consuming manual annotations. More recently, we have developed deep-learning algorithms to fully-automatically track both the mitral valve (MVnet (15)) and also tricuspid valve insertion points (TVnet) (16 ,17) with the TV exhibiting greater motion including rotation vs. the mitral valve. In this study, we utilize a 2D PC sequence, with dynamic slice-prescription based on automatic tracking in 2- and 4-chamber RV cines to determine phase-dependent slice translation and rotation, for prospective valve-tracking PC. This PC approach is called 2.5D PC, because of the partial 3rd dimension.Methods

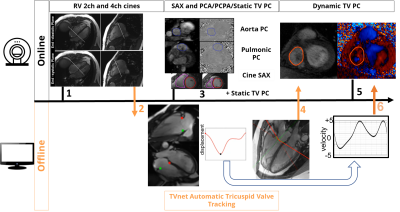

Figure 1 shows the workflow for 2.5D PC. First, RV 2 and 4 chamber cines are acquired and exported to an offline computer for automated tracking of the valve-insertion points, using TVnet. This automated tracking produces the center point of the TV plane and it’s the normal to the TV plane for each time-point in the cardiac cycle. This is automatically input to the customized MRI sequence via a USB device. During the breath-hold, the slice geometry is updated by the sequence at each cardiac phase to match the valve position and orientation. Nine healthy volunteers (36±16y, BMI of 24.9±3.8, 4 females) underwent a cardiac MR (3T Siemens, Erlangen, Germany) that included a standard 4-chamber cine and the less common RV 2-chamber cine, both used for automated valve-tracking by TVnet. The study was approved by our local IRB and all subjects provided informed signed consent. The 2D-PC scan protocol for the TV was: FOV: 380mm, acquisition matrix=256x208, repetition time=5.3ms, echo time=3.4ms, flip angle=15°, voxel size= 1.48x1.48x5-6 mm3, GRAPPA=2, partial Fourier 6/8, through-plane flow-encoding with a VENC of 100cm/s to 150cm/s; temporal resolution of 42ms. This acquisition was performed for a static TV plane coinciding with the valve plane in late-systole and with a dynamic valve-tracking. Standard planimetry of the cine stack yielded SVs, and standard PA and Ao PC were performed to compare resultant SV values. PC analysis was done using Segment software (18), including eddy current compensation, using cardiac phase-dependent ROIs to identify static tissue. The flow velocities were corrected for relative motion of the valve(19), on a pixel by pixel basis, for both static and 2.5D PC flow evaluation.Results

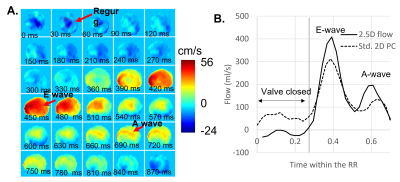

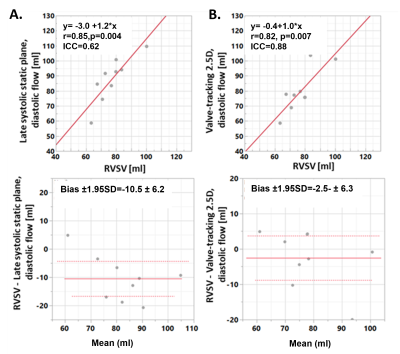

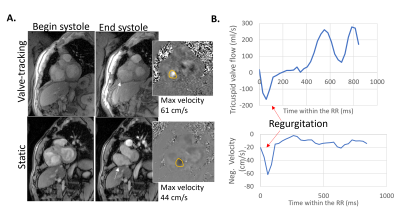

Figure 2 shows a tricuspid flow curve, presenting the flow by PC for the static plane, and the valve-tracking PC. The valve-tracking plane yields a more physiological curve in general, with mainly zero flow in systole, when the valve is shut and flow peaks in diastole corresponding to the E and A wave. 2.5D PC forward flow compared well to stroke volumes by planimetry (RVSV, ICC=0.88, bias ± 2SDs of -2.5 ± 6.3mls, Figure 3B; PA flow, ICC=0.72, bias ± 2SDs of -5.1 ± 15.9mls; LVSV and Aortic flow also agreed well), as expected in healthy subjects. As shown in Figure 3, both static and 2.5D PC were well correlated to RVSV when corrected for relative velocities of the valve, but the 2.5D PC showed a slope closer to unity, a smaller bias, and a much stronger ICC. Figure 4 shows the performance of 2.5D PC in a patient with regurgitation.Discussion

The 2.5D PC method was validated for forward flow, with performance similar to that reported for 4D flow techniques (9,10), and it accurately follows the tricuspid valve. Further studies in patients with regurgitation are needed to define 2.5D PC’s ability to detect regurgitant jets.Acknowledgements

NIH R01HL144706.References

1. Otto CM, Nishimura RA, Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Erwin JP, Gentile F, Jneid H, Krieger EV, Mack M, McLeod C, O'Gara PT, Rigolin VH, Sundt TM, Thompson A, Toly C. 2020 ACC/AHA Guideline for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 2021;143(5):e72-e227.

2. Singh JP, Evans JC, Levy D, Larson MG, Freed LA, Fuller DL, Lehman B, Benjamin EJ. Prevalence and clinical determinants of mitral, tricuspid, and aortic regurgitation (the Framingham Heart Study). The American journal of cardiology 1999;83(6):897-902.

3. Mutlak D, Aronson D, Lessick J, Reisner SA, Dabbah S, Agmon Y. Functional Tricuspid Regurgitation in Patients With Pulmonary Hypertension Is Pulmonary Artery Pressure the Only Determinant of Regurgitation Severity? Chest 2009;135(1):115-121.

4. Nagueh SF, Smiseth OA, Appleton CP, Byrd BF, Dokainish H, Edvardsen T, Flachskampf FA, Gillebert TC, Klein AL, Lancellotti P, Marino P, Oh JK, Popescu BA, Waggoner AD, Echocardiography AS, Imaging EAC. Recommendations for the Evaluation of Left Ventricular Diastolic Function by Echocardiography: An Update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. Eur Heart J-Card Img 2016;17(12):1321-1360.

5. Ramos JG, Fyrdahl A, Wieslander B, Thalen S, Reiter G, Reiter U, Jin N, Maret E, Eriksson M, Caidahl K, Sorensson P, Sigfridsson A, Ugander M. Comprehensive Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Diastolic Dysfunction Grading Shows Very Good Agreement Compared With Echocardiography. Jacc-Cardiovasc Imag 2020;13(12):2530-2542.

6. Uretsky S, Gillam L, Lang R, Chaudhry FA, Argulian E, Supariwala A, Gurram S, Jain K, Subero M, Jang JJ, Cohen R, Wolff SD. Discordance between echocardiography and MRI in the assessment of mitral regurgitation severity: a prospective multicenter trial. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65(11):1078-1088.

7. Uretsky S, Argulian E, Narula J, Wolff SD. Use of Cardiac Magnetic Resonance Imaging in Assessing Mitral Regurgitation: Current Evidence. J Am Coll Cardiol 2018;71(5):547-563.

8. Ton-Nu TT, Levine RA, Handschumacher MD, Dorer DJ, Yosefy C, Fan DL, Hua LQ, Jiang L, Hung J. Geometric determinants of functional tricuspid regurgitation - Insights from 3-dimensional echocardiography. Circulation 2006;114(2):143-149.

9. Feneis JF, Kyubwa E, Atianzar K, Cheng JY, Alley MT, Vasanawala SS, Demaria AN, Hsiao A. 4D Flow MRI Quantification of Mitral and Tricuspid Regurgitation: Reproducibility and Consistency Relative to Conventional MRI. J Magn Reson Imaging 2018;48(4):1147-1158.

10. Driessen MMP, Schings MA, Sieswerda GT, Doevendans PA, Hulzebos EH, Post MC, Snijder RJ, Westenberg JJM, van Dijk APJ, Meijboom FJ, Leiner T. Tricuspid flow and regurgitation in congenital heart disease and pulmonary hypertension: comparison of 4D flow cardiovascular magnetic resonance and echocardiography. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 2018;20(1):5. 11. Kozerke S, Schwitter J, Pedersen EM, Boesiger P. Aortic and mitral regurgitation: Quantification using moving slice velocity mapping. J Magn Reson Imaging 2001;14(2):106-112.

12. Kozerke S, Scheidegger MB, Pedersen EM, Boesiger P. Heart motion adapted cine phase-contrast flow measurements through the aortic valve. Magn Reson Med 1999;42(5):970-978.

13. Seemann F, Heiberg E, Carlsson M, Gonzales RA, Baldassarre LA, Qiu M, Peters DC. Valvular imaging in the era of feature-tracking: A slice-following cardiac MR sequence to measure mitral flow. J Magn Reson Imaging 2019.

14. Seemann F, Pahlm U, Steding-Ehrenborg K, Ostenfeld E, Erlinge D, Dubois-Rande JL, Jensen SE, Atar D, Arheden H, Carlsson M, Heiberg E. Time-resolved tracking of the atrioventricular plane displacement in Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance (CMR) images. Bmc Med Imaging 2017;17. 15. Gonzales RA, Seemann F, Lamy J, Mojibian H, Atar D, Erlinge D, Steding-Ehrenborg K, Arheden H, Hu CX, Onofrey JA, Peters DC, Heiberg E. MVnet: automated time-resolved tracking of the mitral valve plane in CMR long-axis cine images with residual neural networks: a multi-center, multi-vendor study. J Cardiovasc Magn R 2021;23(1).

16. Gonzales R, Lamy J, Thomas K, Zhang Q, Shanmuganathan M, Heiberg E, Ferreira V, Piechnik S, Peters DC. TVnet: automated global analysis of tricuspid valve plane motion in CMR long-axis cines with residual neural networks. European Heart Journal-Cardiovascular Imaging, 23(S2), pp36-37 2022.

17. Gonzales R, Lamy J, Seemann F, Arvidsson P, Murray V, Heiberg E, Peters D. TVnet: Automated Time-Resolved Tracking of the Tricuspid Valve Plane in Long-Axis Cine Images with a Dual Stage Deep Learning Pipeline. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (MICCAI) (pp 567-576) Springer, Cham 2021. 18. Heiberg E, Sjogren J, Ugander M, Carlsson M, Engblom H, Arheden H. Design and validation of Segment--freely available software for cardiovascular image analysis. Bmc Med Imaging 2010;10:1. 19. Kayser HWM, Stoel BC, vanderWall EE, vanderGeest RJ, deRoos A. MR velocity mapping of tricuspid flow: Correction for through-plane motion. J Magn Reson Imaging 1997;7(4):669-673.

Figures