0921

Fast Diffusion fMRI (dfMRI) along the visual pathway closely tracks electrophysiological signals in the negative BOLD regime1Champalimaud Research, Champalimaud Foundation, Lisbon, Portugal

Synopsis

Keywords: fMRI, Multimodal, Preclinical

The underlying sources of negative BOLD responses (NBRs) are still debated. We have recently shown that Positive BOLD response (PBR) to NBR transitions can be induced in the visual pathway by modulating the visual frequency of stimulation, reflecting neural activation/suppression, respectively. Here, we investigate how diffusion functional MRI (dfMRI) signals, which suffer less from vessel contamination, correspond to these activation and suppression regimes. Our results show that dfMRI signals are sharper and more sensitive to suppression induced at high visual stimulation frequencies. Furthermore, striking electrophysiology characteristics such as onsets and offset peaks are more prominent in the dfMRI signals.Introduction

Positive BOLD Responses (PBRS) are known to correlate with increases in local field potentials (LFPs) and multi-unit activity (MUA) signals1,2. However, there is still an ongoing debate on the biological underpinnings of Negative BOLD Responses (NBRs), with evidence pointing to neuronal suppression as the most probable biological scenario3-12.Recently, we employed a visual paradigm capable of modulating visual pathway BOLD responses from activation to suppression13-18 (the latter achieved at high stimulation frequencies) and showed that they corresponded to PBR->NBR transitions. To better understand and characterize the activation / suppression regimes, we harnessed diffusion functional MRI (dfMRI), whose fast responses were previously proposed to rely on neuromorphological coupling19,20, thereby making them more specific to neural activity and less prone to blood vessel contamination21-25. Our findings here reinforce the potential of dfMRI as a better tracker of neural activity.

Methods

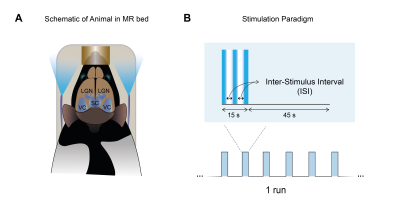

Animal experiments were preapproved by institutional and national authorities and were carried out according to European Directive 2010/63.Long-Evans rats were sedated with medetomidine. Temperature and respiration rates were monitored. Stimulation: A blue LED (𝜆=470nm) was used for binocular stimulation at 1, 15 and 25 Hz (Fig.1A). The paradigm is shown in Fig.1B.

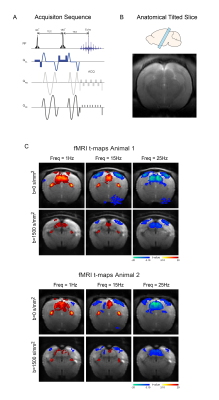

MRI: A 9.4T BioSpec scanner (Bruker, Germany) with an 86mm quadrature resonator for transmittance and a 4-element array cryoprobe26,27 for signal reception was used. Data was acquired at 95%O2 with an isotropically diffusion weighted SE-EPI sequence (TE/TR=37.3/750ms, FOV=18x18mm2, resolution=250x250μm2, slice thickness=1.5mm, b-value=0 and 1500 s/mm2, two consecutive waveforms totalling 24.73ms, tacq=6min45s) – schematic shown in Fig.2A. One tilted slice capturing the entire visual pathways was used (Fig.2B).

Electrophysiology: A NeuroNexus Buzsaki 64 channel probe (8 shanks) was used. Recordings were performed using OpenEphys software (fsampling=30KHz).

Data analysis: MRI pre-processing included manual outlier correction, MP-PCA denoising with a 5x5 kernel, motion correction and smoothing (3D Gaussian kernel, FWHM=0.250mm isotropic). An HRF peaking at 1s was convolved with the stimulation paradigm for the GLM analysis. A minimum significance level of 0.001 with a minimum cluster size of 10 voxels were used. Time-courses were calculated by manually drawing atlas-based28 ROIs and detrending individual runs with a 6th polynomial fit to resting periods.

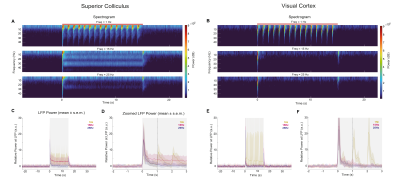

Electrophysiological data was band-passed with a notch filter at 50Hz (and harmonics) to remove power line noise. Time-courses were divided into individual cycles and averaged across channels. The power spectral density (PSD) per run was calculated using a kaiser sliding window with 0.1s width (50% overlap). The PSD integral in the desired frequency band (LFP: 0-150Hz; MUA: 300-3000Hz) was divided by the band width, and z-scored before averaging all runs from different animals.

Results

BOLD responses in the non-diffusion-weighted experiments show strong modulations with increasing stimulation frequency in SC and VC (Fig.2C). VC exhibits NBRs at 15Hz, while SC signals become negative only at the higher frequencies.DfMRI responses in these areas (Fig.2C, bottom panel) appear to follow a similar trend but with more localized responses. To better understand temporal differences between BOLD and dfMRI signals, time-courses are plotted in Fig.3A-C. Several differences can be observed between the two signals: (i) dfMRI amplitudes are larger for all activation/suppression regimes; (ii) dfMRI signals are sharper with faster peak times; (iii) sharp onset and offset dfMRI peaks are observed for VC and SC (red arrows).

We then recorded electrophysiological responses in VC and SC (Fig.4). Strong power decreases with increased frequency were noted and interestingly, while the steady-state reached at 15Hz in SC is still above baseline, the VC power is completely suppressed. This goes along the fMRI responses where cortical NBRs were reached before SC NBRs. For both regions sharp onset/offset peaks are present at the edges of stimulation for higher frequencies.

Discussion

We investigated the relationship of BOLD, dfMRI and electrophysiological signals along the visual pathway with increasing frequencies. DfMRI signals were proposed as a faster functional contrast less prone to vessel contamination and therefore closer to neuronal activity19-25. Our results go in-line with this notion as the dfMRI signals measured along the visual pathway more prominently tracked features of the electrophysiological signals than BOLD responses. Our results also provide insight into the ongoing debate on the nature of negative BOLD signals and their underlying biological underpinnings. Similarities between LFPs and both cortical and SC NBRs in this study point to neuronal suppression as the most probable scenario and provide a system where the amplitude of the NBR can be modulated by a simple experimental variable – the stimulation frequency. One limiting factor of this study is the long stimulation times where accumulation and integration of events occurs. Presenting the animals with shorter stimuli might emphasize even faster and sharper characteristics of the dfMRI signals.Conclusions

Our results suggest that dfMRI signals are potentially better trackers of the electrophysiological signals measured in the VC and SC. NBRs measured in both regions present a similar LFP modulation, suggesting neuronal suppression as the most probable scenario.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Cristina Chavarrías for the implementation of the fMRI in the acquisition MRI sequences and Ms. Francisca Fernandes for the fMRI analysis MATLAB code which was used for the generation of the BOLD t-maps.References

[1] Goense, J. B. M. & Logothetis, N. K. Neurophysiology of the BOLD fMRI Signal in Awake Monkeys. Curr. Biol. 18, 631–640 (2008);

[2] Logothetis, N. K., Pauls, J., Augath, M., Trinath, T. & Oeltermann, A. Neurophysiological investigation of the basis of the fMRI signal. Nature 412, 150–157 (2001);

[3] Stefanovic, B., Warnking, J. M. & Pike, G. B. Hemodynamic and metabolic responses to neuronal inhibition. Neuroimage 22, 771–778 (2004);

[4] Shmuel, A. et al. Sustained negative BOLD, blood flow and oxygen consumption response and its coupling to the positive response in the human brain. Neuron 36, 1195–1210 (2002);

[5] Sten, S. et al. Neural inhibition can explain negative BOLD responses: A mechanistic modelling and fMRI study. Neuroimage 158, 219–231 (2017);

[6] Pasley, B. N., Inglis, B. A. & Freeman, R. D. Analysis of oxygen metabolism implies a neural origin for the negative BOLD response in human visual cortex. Neuroimage 36, 269–276 (2007);

[7] Boorman, L. et al. Negative Blood Oxygen Level Dependence in the Rat:A Model for Investigating the Role of Suppression in Neurovascular Coupling. J. Neurosci. 30, 4285–4294 (2010);

[8] Muthukumaraswamy, S. D., Edden, R. A. E., Jones, D. K., Swettenham, J. B. & Singh, K. D. Resting GABA concentration predicts peak gamma frequency and fMRI amplitude in response to visual stimulation in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 106, 8356–8361 (2009);

[9] Shmuel, A., Augath, M., Oeltermann, A. & Logothetis, N. K. Negative functional MRI response correlates with decreases in neuronal activity in monkey visual area V1. Nat. Neurosci. 9, 569–577 (2006);

[10] Boillat, Y., Xin, L., van der Zwaag, W. & Gruetter, R. Metabolite concentration changes associated with positive and negative BOLD responses in the human visual cortex: A functional MRS study at 7 Tesla. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 40, 488–500 (2020);

[11] Northoff, G. et al. GABA concentrations in the human anterior cingulate cortex predict negative BOLD responses in fMRI. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 1515–1517 (2007);

[12] Devor, A. et al. Suppressed Neuronal Activity and Concurrent Arteriolar Vasoconstriction May Explain Negative Blood Oxygenation Level-Dependent Signal. J. Neurosci. 27, 4452–4459 (2007);

[13] Van Camp, N., Verhoye, M., De Zeeuw, C. I. & Van der Linden, A. Light Stimulus Frequency Dependence of Activity in the Rat Visual System as Studied With High-Resolution BOLD fMRI. J. Neurophysiol. 95, 3164–3170 (2006);

[14] Pawela, C. P. et al. Modeling of region-specific fMRI BOLD neurovascular response functions in rat brain reveals residual differences that correlate with the differences in regional evoked potentials. Neuroimage 41, 525–534 (2008);

[15] Bailey, C. J. et al. Analysis of time and space invariance of BOLD responses in the rat visual system. Cereb. Cortex 23, 210–222 (2013);

[16] Niranjan, A., Christie, I. N., Solomon, S. G., Wells, J. A. & Lythgoe, M. F. fMRI mapping of the visual system in the mouse brain with interleaved snapshot GE-EPI. Neuroimage 139, 337–345 (2016);

[17] Gil, R.; F. Fernandes, F.; Shemesh, N.; Increased negative BOLD responses along the rat visual pathway with short inter-stimulus intervals [abstract]. In: 2020 ISMRM and SMRT Annual Meeting and Exhibition; 08-14 August 2020; Virtual conference;

[18] Gil, R.; Valente, M.; Renart, A., Shemesh, N.; Negative BOLD closely follows neuronal suppression in superior colliculus [abstract]. In: 2022 ISMRM and SMRT Annual Meeting and Exhibition; 07-12 May 2022;

[19] Nunes, D., Gil, R. & Shemesh, N. A rapid-onset diffusion functional MRI signal reflects neuromorphological coupling dynamics. Neuroimage 231, 117862 (2021);

[20] Le Bihan, D., Urayama, S. I., Aso, T., Hanakawa, T. & Fukuyama, H. Direct and fast detection of neuronal activation in the human brain with diffusion MRI. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 103, 8263–8268 (2006);

[21] Bai, R., Stewart, C. V., Plenz, D. & Basser, P. J. Assessing the sensitivity of diffusion MRI to detect neuronal activity directly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, E1728–E1737 (2016);

[22] Kim, S.-G., Lee, S.-P., Silva, A. C. & Ugurbil, K. Diffusion-weighted spin-echo fMRI at 9.4 T: Microvascular/tissue contribution to BOLD signal changes. Magn. Reson. Med. 42, 919–928 (1999);

[23] Rudrapatna, U. S., van der Toorn, A., van Meer, M. P. A. & Dijkhuizen, R. M. Impact of hemodynamic effects on diffusion-weighted fMRI signals. Neuroimage 61, 106–114 (2012);

[24] Tsurugizawa, T., Ciobanu, L. & Le Bihan, D. Water diffusion in brain cortex closely tracks underlying neuronal activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 110, 11636–11641 (2013);

[25] Kohno, S. et al. Water-diffusion slowdown in the human visual cortex on visual stimulation precedes vascular responses. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 29, 1197–1207 (2009);

[26] Niendorf, T. et al. Advancing cardiovascular, neurovascular, and renal magnetic resonance imaging in small rodents using cryogenic radiofrequency coil technology. Front. Pharmacol. 6, 1–21 (2015);

[27] Baltes, C., Radzwill, N., Bosshard, S., Marek, D. & Rudin, M. Micro MRI of the mouse brain using a novel 400 MHz cryogenic quadrature RF probe. NMR Biomed. 22, 834–842 (2009);

[28] Paxinos, G; Franklin, K. Mouse Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. (2001).

Figures