0919

Direct detection of neural activity in humans by ultrafast high-sensitivity SLAM MRI at 3T1Key Laboratory for Biomedical Engineering of Ministry of Education, Department of Biomedical Engineering, College of Biomedical Engineering & Instrument Science at Zhejiang University; and the Department of Radiology, Children’s Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2Division of MR Research, Department of Radiology, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, United States, 3Philips Healthcare, Cleveland, OH, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: fMRI, fMRI

The direct MRI detection of neural activity in humans is a long-sought goal that has been attempted by many. We posit that a key reason for prior failures is inadequate sensitivity. Spectroscopy with linear algebraic modeling (SLAM) is a compartmental imaging method that provides enormous gains in speed and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). Here we use it to directly obtain MRI signals from arbitrarily-shaped brain regions with arguably the highest possible SNR efficiency. We successfully detect neural responses elicited by rhythmic finger-tapping at the tapping frequency in humans at 3T, as confirmed by simultaneously-acquired EEG data.Introduction

The direct detection of neural activity in humans using MRI is a long-sought goal of many research groups(1). While a direct detection of neural activity was recently reported for mice at 9.4T(2), to our knowledge, there have been no positive reports of the direct MRI detection of neural activity in humans for over a decade. We posit that a key reason for such failure is the available sensitivity for detecting sub-picoTesla magnetic fluctuations, against a background of intrinsic dipolar NMR processes. Here, we use an ultrafast compartmental imaging method–spectroscopy with linear algebraic modeling SLAM(3-7)–to directly record compartmental signals from arbitrarily-shaped regions with arguably the highest possible signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) efficiency, at a temporal resolution of up to ~25Hz. In this work, SLAM data were acquired during a finger-tapping task with simultaneous electroencepahologram (EEG) recording inside a 3T MRI scanner, to directly probe rhythmic neural motor activity in humans.Methods

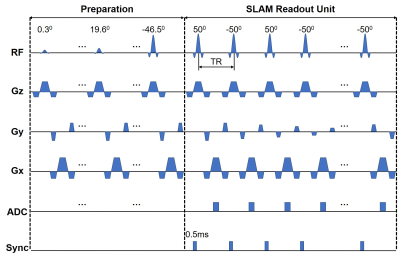

MRI data were acquired from 6 healthy normal volunteers on a standard 3T human scanner using a 64-channel head coil. The in vivo studies were approved by the local Institutional Review Board, with written consent forms obtained from every participant. The MRI acquisition protocol consisted of sensitivity reference, T1-weighted, blood oxygenation level-dependent (BOLD)(8), regular balanced steady-state free precession (bSSFP)(9), and SLAM bSSFP scans. The BOLD and SLAM acquisitions were done with simultaneous EEG readout using a 32-channel MRI-compatible EEG system.The bSSFP sequence (Fig. 1) commenced with a preparation module before applying the SLAM readout module comprised of constant flip angles (FA) of ±500 and a 0.5ms gating pulse to synchronize the physiologic stimulation apparatus and the EEG with the start of each RF pulse. Sinc-shaped 1.2ms RF pulses were applied at a repetition time (TR) of 3.96ms with 10 gradient phase-encoding steps for each SLAM readout interval, stepped from -5 to +4 in central k-space. The 10 phase-encoded k-space acquisitions along with user-defined segmentation information from associated MRI scans, were input into the SLAM algorithm to directly reconstruct the signals from whole arbitrarily-shaped compartments(3-7). This resulted in an effective temporal brain sampling frequency of 25.3Hz, with the potential to detect MRI fluctuations within a ~12Hz power spectrum of neural activity, upon Fourier transformation (FT).

The 2D SLAM bSSFP and regular bSSFP sequences used TR=3.96ms, echo-time (TE)=1.98ms, field-of-view (FOV)=220x220mm2, slice thickness=19mm, resolution=1.15x1.15mm2, and prescribed matrix size=192x192, with the imaging slab covering the motor cortex. The regular bSSFP sequence, used to segment compartments for SLAM reconstruction, acquired all the 192 k-space lines with a total duration of 2.3s, while the SLAM bSSFP sequence only acquired the central ten k-space lines with 5501 repeated measurements for a total duration of 3.65min. The BOLD scan deployed a 2D gradient-echo echo-planar-imaging (EPI) sequence(10) with FA=200, TR=68ms, TE=25ms, FOV=220x220mm2, resolution=3.44x3.44mm2, slice thickness=19mm, a transverse orientation matching the SLAM slab positioning, 3088 repeated measurements, and a total duration of 3.55min.

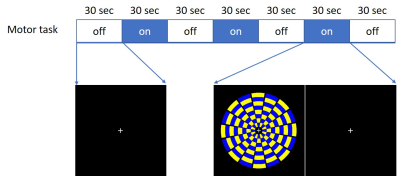

A projector placed next to the MRI scanner was used to facilitate motor stimulation paradigms, which were visualized by volunteers via a mirror on top of the head coil. The stimulation task used commercial software to control timing. Volunteers performed a visually-cued finger-tapping task composed of alternating 30s resting and 30s active parts (Fig. 2). During the resting parts, the volunteers saw a fixed picture and kept the hand open. During the active parts, volunteers tapped fingers synchronously with the rhythm of a flickering checkerboard. A ~1.47Hz flickering rate was chosen to avoid other physiological signals in the ~12Hz power spectrum.

Results

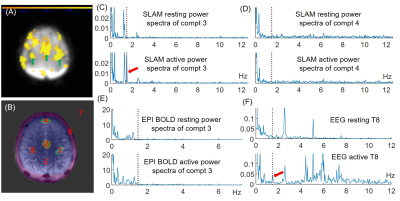

Fig. 3A exemplifies activated primary motor and supplementary sensorimotor regions (green arrows), accompanied by some other non-motor-related activated areas on the BOLD activation map, which was possibly due to low SNR in this subject. Fig. 3B shows the SLAM segmentation for 7 whole compartments including motor (#1-3) and several control (#4-7) compartments. A clear peak at the 1.47Hz finger-tapping frequency appeared in power spectra acquired during the active parts in motor compartments #1-3 (Figs. 3C), but not during the resting parts. No 1.47Hz peaks were observed in the control compartment #4 during rest or active protocols (Fig. 3D). No tapping peak was detectable in any power spectra derived by FT of the EPI data (Fig. 3E) from the same compartments defined for SLAM, while respiratory peaks are observed at the same frequencies as in SLAM. Importantly, EEG power spectra acquired simultaneously with SLAM demonstrate the same 1.47Hz peaks in the active session (Fig. 3E). Other peaks are mostly attributable to cardiac and respiratory cycles. Similar MRI results were recorded from 4 of this study cohort.Conclusion

The SLAM method successfully detected neural responses elicited by sub-second rhythmic finger-tapping in motor areas of the brains of 4 of 6 healthy subjects, synchronous with the tapping frequency, and consistent with simultaneously-acquired EEG data. In contrast, contemporaneous conventional EPI BOLD was unable to detect the same rhythmic neural activity. This work opens a new window for probing neural activity directly in humans using standard clinical 3T MRI systems.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Bandettini PA, Petridou N, Bodurka J. Direct detection of neuronal activity with MRI: Fantasy, possibility, or reality? Appl Magn Reson 2005;29(1):65-88.

2. Toi PT, Jang HJ, Min K, Kim SP, Lee SK, Lee J, Kwag J, Park JY. In vivo direct imaging of neuronal activity at high temporospatial resolution. Science 2022;378(6616):160-168.

3. Zhang Y, Gabr RE, Schar M, Weiss RG, Bottomley PA. Magnetic resonance Spectroscopy with Linear Algebraic Modeling (SLAM) for higher speed and sensitivity. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2012;218:66-76.

4. Zhang Y, Gabr RE, Zhou J, Weiss RG, Bottomley PA. Highly-accelerated quantitative 2D and 3D localized spectroscopy with linear algebraic modeling (SLAM) and sensitivity encoding. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 2013;237:125-138.

5. Zhang Y, Heo HY, Jiang S, Lee DH, Bottomley PA, Zhou J. Highly accelerated chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) measurements with linear algebraic modeling. Magnetic resonance in medicine 2016;76(1):136-144.

6. Zhang Y, Liu X, Zhou J, Bottomley PA. Ultrafast compartmentalized relaxation time mapping with linear algebraic modeling. Magnetic resonance in medicine 2018;79(1):286-297.

7. Bottomley PA, Zhang Y. Accelerated Spatially Encoded Spectroscopy of Arbitrarily Shaped Compartments Using Prior Knowledge and Linear Algebraic Modeling. eMagRes 2015;4:89-104.

8. Ogawa S, Lee TM, Kay AR, Tank DW. Brain magnetic resonance imaging with contrast dependent on blood oxygenation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1990;87(24):9868-9872.

9. Bieri O, Scheffler K. Fundamentals of balanced steady state free precession MRI. Journal of magnetic resonance imaging : JMRI 2013;38(1):2-11.

10. Stehling MK, Turner R, Mansfield P. Echo-planar imaging: magnetic resonance imaging in a fraction of a second. Science 1991;254(5028):43-50.

Figures