0914

Quantum-Sensing MRI for Non-Invasive Detection of Neuronal Firing in Human Brain: Initial Demonstration via Finger-Tapping Task1Radiology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 2Neurology, NYU Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States, 3Neurology, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY, United States, 4Radiology, NYU Langone Health, New York, NY, United States, 5Radiology, Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Nerves, Neuro, fMRI (task)

Neuronal firing is the electrophysiological basis of brain function. BOLD-based functional MRI indirectly detects neuronal activity through an uncertain neuro-hemodynamic mechanism and is also limited to the detection of slow neuronal activity such as postsynaptic potentials due to its relatively low temporal resolution. Recent efforts have improved temporal resolution to milliseconds or even sub-milliseconds, under the assumption that neuronal activity is exactly repeatable in time, though unlikely to be practical. Here we demonstrate the potential of quantum-sensing MRI to directly detect neuronal firing using a finger-tapping task.INTRODUCTION

Neurons fire action potentials that travel down axons and across synapses for communication to postsynaptic neurons. Traveling action potentials generate electric currents in axons (~2ms in duration) and postsynaptic dendrites (~10–100ms in duration). Neuronal currents produce electric and magnetic fields detectable by scalp electroencephalography (EEG) and magnetoencephalography (MEG) 1,2. However, they detect these fields relatively far away from firing sources (~20mm), and limit sensitivity to slow, easily-synchronized postsynaptic currents in a large volume 1,3-5. Functional MRI (fMRI) is currently based on the blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signals 6,7 and indirectly detects neuronal activity through an uncertain neuro-hemodynamic mechanism. fMRI is also limited to the detection of slow neuronal activity such as postsynaptic potentials due to its relatively low temporal resolutions (40–100ms) 8. Recent research efforts have improved temporal resolution to milliseconds 9 or sub-milliseconds 10, under the assumption that neuronal activity is exactly repeatable in time, though unlikely to be practical. To tackle these challenges, a new concept was recently reported in which quantum sensing is used to detect magnetic fields related to both fast (action potential) and slow (postsynaptic) neuronal currents at high temporal resolution and high spatial localization of firing sources 11,12. Here we demonstrate the feasibility of quantum-sensing (qs) MRI using a finger-tapping task which is widely used in current BOLD-based fMRI.THEORY

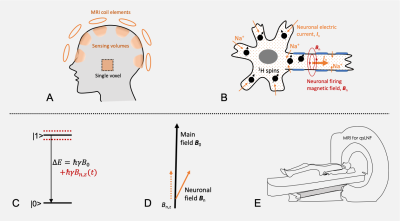

The concept of qsMRI is illustrated in Fig. 1 and a brief description is as follows 11. The quantum sensors are endogenous proton (1H) nuclear spins of water molecules inside neurons, with two quantum states, |0> and |1>, in a static external magnetic field B0 provided by MRI machine. The quantum sensing process is electromagnetic interaction between these nuclear spins at superposition state (achieved by an exciting RF pulse) and neuronal magnetic field, Bn(r, t). During the sensing period, nuclear spins accumulate an extra phase which is encoded in the free induction decay (FID). The readout of spins’ state is implemented by RF receive coils placed around the head (Fig. 1) during data acquisition of FID signal which results from an ensemble of spins in a coil-specific investigation volume. A phase difference between neighboring data points in FID is calculated for the estimate of firing field z-component, Bn,z.METHODS

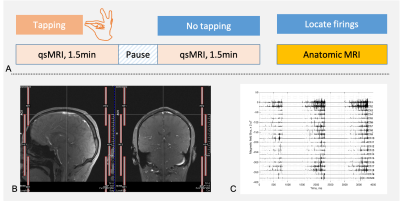

The study design is summarized in Fig.2. Six healthy subjects (age of 48.5±17.1 years, 4 males and 2 females, 5 right- and 1 left-handed) were studied, with an IRB-approved consent. Finger-tapping task was performed by subject’s index finger in the dominant hand (Fig. 2a). The rate of tapping was 1.0Hz, lasting for 1.5min. FID signals were acquired at task- and resting states using vendor’s pulse sequence fid on a 3T scanner (Prisma, Siemens), with a standard Head/Neck 20-channel array coil (Figs. 2b). FID readout time is 819.2ms at a sampling interval of 0.2ms, with TE/TR=0.2/1500ms, flip angle=90º, and repeats=64. A custom-developed software in MATLAB R2021a (MathWorks, Natick, MA) was used to calculate firing field Bn,z (Fig. 2c). The sensing volumes in the brain were defined by anatomic images at individual coil channels.RESULTS

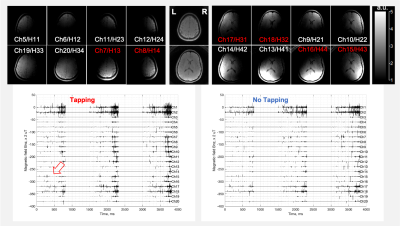

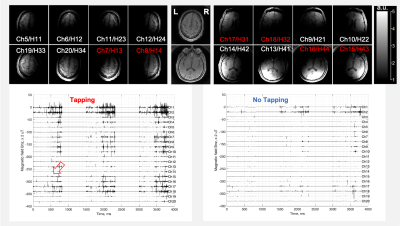

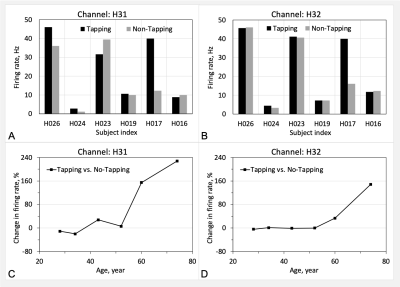

Fig. 3 presents typical qsMRI outcomes from a healthy study subject (43-year-old female, right-handed), while Fig. 4 shows the results from another healthy study subject (74-year-old male, normal cognition, right-handed). Fig. 5 summarizes, across the six studied subjects, the firing rate and its change between with and without the tapping task, specifically in two regions of interest: prefrontal lobe on the left side and on both left and right sides. The firing rate was found substantially different among subjects, but the tapping task activated neuronal firings in all the subjects studied. The right-handed tapping clearly increased firing rate in the left side of prefrontal lobe (as expected), but also altered the right side of the brain (not expected). The tapping-induced change in firing rate seems increasing with age, or the old brains are quieter than the young at no-tapping task.DISCUSSION

Figs. 3–5 showed the potential for qsMRI to detect neuronal firing activated by finger-tapping task. Notably, the change in firing rate is large enough to quantify neuronal response to finger-tapping task at individual subject level. However, due to the small sample size of study subjects, the statistical significance of these results needs to be confirmed in the future.CONCLUSION

The human studies presented support the proposed quantum-sensing MRI to detect neuronal firings activated by finger-tapping task. These promising preliminary results will encourage further studies on the qsMRI for non-invasive detection of neuronal firings in response to more challenging tasks in different neurological conditions in a wide range of age groups.Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported in part by the NIH RF1 AG067502 and the General Research Fund of the Department of Radiology. This work was also performed under the rubric of the Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research (CAI2R, www.cai2r.net), an NIBIB Biomedical Technology Resource Center (NIH P41 EB017183).References

1. Buzsáki G, Anastassiou CA, Koch C. The origin of extracellular fields and currents--EEG, ECoG, LFP and spikes. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(6):407-420.

2. Hennig J, Kiviniemi V, Riemenschneider B, et al. 15 Years MR-encephalography. MAGMA. 2021; 34:85-108.

3. Bandettini PA, Petridou N, Bodurka J. Direct detection of neuronal activity with MRI: Fantasy, possibility, or reality? Applied Magnetic Resonance. 2005; 29:65–88.

4. Boudurka J, Bandettini PA. Toward direct mapping of neuronal activity: MRI detection of ultra-weak, transient magnetic field changes. Magn Reson Med. 2002;47(6):1052-1058.

5. Baillet S. Magnetoencephalography for brain electrophysiology and imaging. Nat Neurosci. 2017; 20:327–339

6. Ogawa S, Menon RS, Tank DW, Kim SG, Merkle H, Ellermann JM, Ugurbil K. Functional brain mapping by blood oxygenation level-dependent contrast magnetic resonance imaging. A comparison of signal characteristics with a biophysical model. Biophysical journal. 1993 Mar 1;64(3):803-12.

7. Ogawa S, Tank DW, Menon R, Ellermann JM, Kim SG, Merkle H, Ugurbil K. Intrinsic signal changes accompanying sensory stimulation: functional brain mapping with magnetic resonance imaging. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1992 Jul 1;89(13):5951-5.

8. Huang J. Detecting neuronal currents with MRI: a human study. Magn Reson Med. 2014;71(2):756-762

9. Toi PT, Jang HJ, Min K, Kim SP, Lee SK, Lee J, Kwag J, Park JY. In vivo direct imaging of neuronal activity at high temporospatial resolution. Science. 2022 Oct 14;378(6616):160-8.

10. Zhong Z, Sun K, Karaman MM, Zhou XJ. Magnetic resonance imaging with submillisecond temporal resolution. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine. 2021 May;85(5):2434-44.

11. Qian Y, Calderon L, Chen X, Liu A, Lui YW, Boada, FE. Quantum sensing of local neuronal firings (qsLNF) in human brains via proton (1H) MRI: Proof of concept. In Proceedings of the Joint Annual Meeting ISMRM-ESMRMB 07–12 May 2022 in London, UK, page 4088.

12. Qian Y, Lakshmanan K, Liu A, Lui YW, Boada, FE. Magnetic resonance recording of local neuronal firings (mrLNF) in the human brains: A proof of concept. In Proceedings of the 29th Annual Meeting ISMRM (Virtual), 15–20 May 2021, page 102.

Figures

Fig. 1. Quantum-sensing MRI for neuronal firing detection. a) Quantum-sensing volumes defined by coil sensitivity (shading areas) or by single-voxel excitation. b) Micro quantum sensors of proton (1H) nuclear spins (black dots) in sodium (Na+) ionic flow (neuronal current) in a firing neuron. c) Quantum sensing of neuronal magnetic field Bn,z(t) by proton spins transiting from excited state |1> to ground state |0>, with an energy ∆E varying with neuronal field around the main field B0 . d) Modulation of neuronal firing Bn onto B0. e) Recording of neuronal firing via MRI machine.

Fig. 2. a) Finger-tapping task and quantum-sensing MRI. Finger-tapping is instructed by MRI operator and performed by the subject using index finger of the dominant hand. qsMRI scan starts after the tapping at a tapping rate of 1.0Hz and lasting for 1.5min, followed by a pause for 1.0min. qsMRI is repeated without finger-tapping. Anatomic MRI acquires individual coil-channel images to locate the sources of qsMRI signals. b) Locations of the coil elements in a Head/Neck 20Ch array, HE1-2, HE3-4, and NE1-2. c) A qsMRI recording of neuronal firing (a 3-TR-long segment) at resting-state.

Fig. 3. A qsMRI recording (the first 3 TRs) from the brain of a healthy subject (43-year-old female, right-handed) acquired with a 20-channel Head/Neck coil at 3T. TOP: MRI images of sensing volume at individual elements (the neck channels are not shown). In the middle are the combined images (sum-of-squares). BOTTOM: qsMRI recordings from each channel with and without finger tapping. Firing peaks (fat arrow) are more popular (red channels) during the tapping than no-tapping. The Neck channels have larger random noise in anterior (NE1/Ch1-2) than posterior (NE2/Ch3-4).

Fig. 4. A representative qsMRI recording (the first 3 TRs) from the brain of a healthy study subject (74-year-old male, normal cognition, right-handed) acquired with a 20-channel Head/Neck coil array at 3T. TOP: MRI images of sensing volume at individual coil elements (the neck channels are not shown). In the middle are the combined images (sum-of-squares). BOTTOM: The qsMRI recordings from each channel with and without finger tapping. The firing peaks (fat arrow) are more popular (red color channels) during the tapping than no-tapping.

Fig. 5. Firing rate and change between with and without the finger tapping, in the prefrontal lobe left side (Channel H31) and both side (Channel H32). a,b) Firing rate. c,d) Age-related change in firing rate. The study subjects are right-handed, except H023 (left-handed).