0903

Ultrafast Z-spectroscopic Imaging in vivo at 3T using through-slice spectral encoding (TS-UFZ)1F.M. Kirby Research Center for Functional Brain Imaging, Kennedy Krieger Institute, BALTIMORE, MD, United States, 2The Russell H. Morgan Department of Radiology, The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine, BALTIMORE, MD, United States, 3Department of Information Science and Technology, Northwest University, Xi’an, China, 4Philips Healthcare, Baltimore, MD, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: CEST & MT, CEST & MT

Acquisition of high-resolution Z-spectra requires excessive scan times. Ultrafast Z-spectroscopy (UFZ) can obtain whole Z-spectra within one acquisition by encoding the Z-spectral dimension spatially via a gradient applied concurrently with the saturation RF pulse, significantly reducing the scanning time. Still, UFZ has had limited success in vivo due to tissue heterogeneity. Here, we developed a TS-UFZ imaging approach where both saturation gradient and its readout were applied in the slice direction, where there is minimal heterogeneity. Results show that TS-UFZ allows high spectral- and spatial-resolution imaging of CEST signals in phantoms and human brain at 3T.Introduction

CEST data are often acquired as a function of saturation frequency to create water saturation spectra or Z-spectra.1 As each frequency constitutes an image acquisition, high Z-spectral resolution requires many acquisitions, which leads to excessive scanning time. Ultrafast Z-spectroscopy (UFZ) can address this by encoding the Z-spectral dimension spatially via a gradient applied concurrently with the saturation pulse and consequently acquires the whole Z-spectrum within one acquisition.2-4 In UFZ, the frequency offset of the spins depends on their spatial location in relation to the gradient isocenter and gradient strength. Several groups have implemented UFZ approaches in vivo,5-7 but these previous studies could only obtain Z-spectra from a single voxel and could not map CEST signals across a slice. Here, we show that applying the saturation gradient and image readout along the slice direction and phase encoding in-plane allows for generating acceptable high spectral-resolution CEST images using UFZ.Materials and Methods

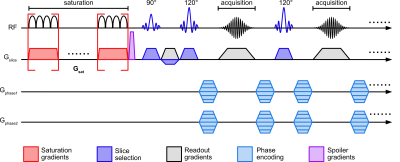

MRI acquisitionThe TS-UFZ method was implemented using a 3D SE sequence (Figure 1). The preparation period consisted of a gradient applied concurrently with RF saturation pulse. To compensate for possible droop on the gradient amplifier, a train of short gradient pulses was used. The saturation period was 2s (B1,sat = 0.5 µT) and followed by a multi-shot TSE readout. Both saturation gradient and imaging readout were applied along the slice direction, resulting in a relatively uniform voxel composition. Phase-encoding was applied in both in-plane directions, allowing for additional under-sampling and acceleration. A 3s delay was included before each saturation module for magnetization recovery. Following the acquisition of the saturation image (Ssat), a reference scan (S0) was acquired with the saturation pulse center applied far off-resonance.

For comparison, conventional Z-spectral images using a single-shot TSE readout were acquired with the same saturation duration and B1 as TS-UFZ, but Z-spectral data was acquired by varying the frequency offsets of the saturation pulse.

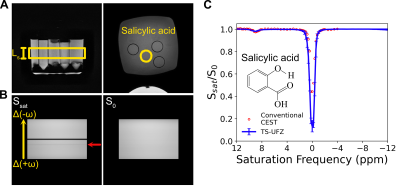

TS-UFZ was validated in vitro (salicylic acid and egg-white phantoms) and then tested in vivo on three healthy volunteers according to institutional guidelines. All participants signed informed consent. All MRI scans were performed on a 3T Philips Elition RX system (Philips Healthcare).

Data processing

For TS-UFZ, B0 field inhomogeneities were corrected by shifting the nominal saturation frequency list for each voxel to ensure the frequency offset of water peak was at 0 ppm. For conventional CEST, B0 shifts were corrected by using the WASSR method8. Then, after normalization with S0 image or spectra, the Z-spectrum was interpolated to 0.2 ppm step size and PCA-based denoising9 was employed to improve SNR for both techniques. The APT signal was extracted by fitting the background Z-spectrum and integrating the residual spectrum between 3 to 4 ppm.

Results

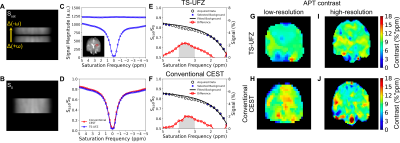

In phantoms, TS-UFZ imaging under various Gsat provided Z-spectra of salicylic acid and egg white in excellent agreement with the conventional Z-spectral acquisition (Figures 2, 3). In vivo, we noticed lower saturation for the Z-spectral baseline, attributed to bulk flow through the imaging slice, but this was addressed by fitting the background spectrum and extracting the CEST contrast from the residual signal. APT contrast intensities obtained by TS-UFZ were on the same order of magnitude as conventional CEST but contrast varied across the slice (Figure 4). The difference is likely due to the TS-UFZ image (1 ppm integral) representing a 0.5 mm sub-slice while the conventional CEST signal is the average over a 10 mm slice.Discussion

The feasibility of TS-UFZ imaging approach was demonstrated in vitro and in vivo at 3T. TS-UFZ reduces scan time because saturation pulses are only applied at two frequency offsets (Ssat and S0). The Z-spectral resolution is determined by the slice thickness, saturation gradient strength, and the number of points in the readout direction. The scan time is dependent on the number of shots required to acquire the in-plane image resolution. Compared to conventional CEST (54 offsets, 6 mins and 6 s), in vivo TS-UFZ imaging required only a quarter of the scan time for low-resolution images (96 offsets, 1 min and 28 s, in-plane voxel size of 8 × 8 mm2). Still, several acceleration methods can be applied to the phase-encoding steps to further reduce the acquisition time, e.g., compressed sensing and parallel imaging10-13. This was demonstrated on the egg white phantom where the in-plane SENSE factor of 2 × 1 reduced the scan time for a whole Z-spectrum to 53 s.Conclusion

The proposed TS-UFZ imaging method is an extension of gradient-encoded ultrafast Z-spectroscopy and has spectroscopic imaging capabilities, enabling to distinguish CEST effects in both phantom and in vivo applications at 3T.Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Xiang Xu for valuable discussions. This research was supported by NIH grants P41031771 and R01 EB015032. C.B. thanks China Scholarship Council (201906970024) for financial support. Under a license agreement between Philips and the Johns Hopkins University, Dr. van Zijl and Johns Hopkins University are entitled to fees related to an imaging device used in the study discussed in this publication. Dr. van Zijl also is a paid lecturer for Philips and receives research support from Philips. This arrangement has been reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins University in accordance with its conflict of interest policies.References

1. Grad, J. & Bryant, R. G. Nuclear magnetic cross-relaxation spectroscopy. J. Magn. Reson. 90, 1-8 (1990).

2. Swanson, S. D. Broadband excitation and detection of cross-relaxation NMR spectra. J. Magn. Reson. 95, 615-618 (1991).

3. Xu, X., Lee, J.-S. & Jerschow, A. Ultrafast Scanning of Exchangeable Sites by NMR Spectroscopy. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 8281-8284 (2013).

4. Boutin, C., Léonce, E., Brotin, T., Jerschow, A. & Berthault, P. Ultrafast Z-Spectroscopy for 129Xe NMR-Based Sensors. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 4, 4172-4176 (2013).

5. Zhang, Y., Zu, T., Liu, R. & Zhou, J. Acquisition sequences and reconstruction methods for fast chemical exchange saturation transfer imaging. NMR in Biomedicine n/a, e4699 (2022).

6. Liu, Z., Dimitrov, I. E., Lenkinski, R. E., Hajibeigi, A. & Vinogradov, E. UCEPR: Ultrafast localized CEST-spectroscopy with PRESS in phantoms and in vivo. Magn Reson Med 75, 1875-1885 (2016).

7. Wilson, N. E., D'Aquilla, K., Debrosse, C., Hariharan, H. & Reddy, R. Localized, gradient-reversed ultrafast z-spectroscopy in vivo at 7T. Magn Reson Med 76, 1039-1046 (2016).

8. Kim, M., Gillen, J., Landman, B. A., Zhou, J. & van Zijl, P. C. M. Water saturation shift referencing (WASSR) for chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) experiments. Magn. Reson. Med. 61, 1441-1450 (2009).

9. Breitling, J. et al. Adaptive denoising for chemical exchange saturation transfer MR imaging. NMR Biomed 32, e4133 (2019).

10. Liang, D., Liu, B., Wang, J. & Ying, L. Accelerating SENSE using compressed sensing. Magn Reson Med 62, 1574-1584 (2009).

11. Feng, L. et al. Golden-angle radial sparse parallel MRI: Combination of compressed sensing, parallel imaging, and golden-angle radial sampling for fast and flexible dynamic volumetric MRI. Magn Reson Med 72, 707-717 (2014).

12. Zhu, H., Jones, C. K., van Zijl, P. C. M., Barker, P. B. & Zhou, J. Fast 3D chemical exchange saturation transfer (CEST) imaging of the human brain. Magn. Reson. Med. 64, 638-644 (2010).

13. Zhao, X. et al. Three-dimensional turbo-spin-echo amide proton transfer MR imaging at 3-Tesla and its application to high-grade human brain tumors. Mol Imaging Biol 15, 114-122 (2013).

Figures