0890

Brownian superparamagnetic iron oxide nanoparticles enable therapeutic cell viability monitoring with Magnetic Particle Imaging1Stanford University, Stanford, CA, United States, 2University of California, Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Molecular Imaging, Cell Tracking & Reporter Genes

Molecular imaging tools can noninvasively track cells in vivo. However, no techniques today can rapidly monitor cell therapies to allow for nimble treatment optimization for each patient, the epitome of Personalized Medicine. Magnetic Particle Imaging (MPI) is a new tracer imaging technology that could soon provide MDs unequivocal therapy treatment feedback in just three days. MPI with Brownian SPIOs shows promise towards noninvasive sensing of cell viability via viscosity changes in apoptotic cells. This unique ability could greatly improve the efficacy of cell therapies by enabling rapid personalization of the treatment.Introduction

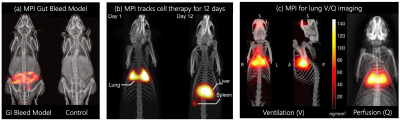

There are now over 1,000 cell therapies in clinical trials. Current molecular imaging methods, including MRI with 19F or superparamagnetic iron oxide (SPIO), ultrasound with microbubbles and nuclear medicine with radioisotopes, all have limitations in persistence, sensitivity, resolution or artifacts. No cell tracking tools today can fully and rapidly assess treatment efficacy to allow for nimble treatment optimization for each patient. For example, immunotherapy has become a mainstream treatment of bloodborne cancers (10% of all tumors), but it remains an open challenge for “solid tumors,” which account for 90% of tumors [1]. Magnetic Particle Imaging (MPI) is a new imaging method ideal for tracking cells. It could soon allow MDs to gauge treatment efficacy directly and rapidly—in just three days. MPI offers ideal micromolar sensitivity; positive, linear and quantitative contrast with 100-fold higher SNR/cell compared to 19F MRI; zero radiation, robust penetration and no artifacts anywhere in the body—including in the lungs and inside bones (Fig. 1) [2–8].An outstanding challenge for all cell tracking methods is distinguishing live from dead cells. Cellular viscosity changes when cells undergo apoptosis [9], but T2* or 19F signal does not reflect such a change. Other imaging techniques could potentially discern cell viability through genetic manipulation, but they are often not translational.

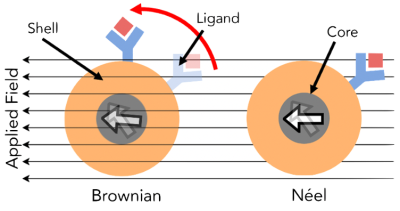

MPI scanning requires an 180-degree rotation of the SPIO. This rotation time is slowed by Néelian and Brownian relaxation constants (Fig. 2) [10]. Néelian and Brownian relaxation in MPI is akin to T1 and T2 in MRI. In Néelian relaxation, the SPIO domain flips with no physical rotation, so Néelian SPIOs cannot sense viscosity changes. With Brownian relaxation, the entire SPIO aligns with the field, so Brownian relaxation scales linearly with the nanoscale viscosity [11]. Since Néelian and Brownian relaxation occurs in parallel, we observe the faster of the two. Here, we demonstrate for the first time promising data showing that Brownian MPI particles can infer cell death via viscosity sensing.

Methods

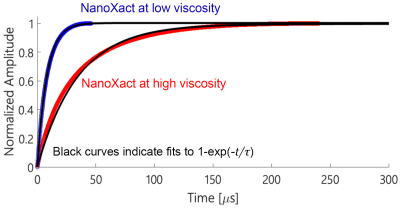

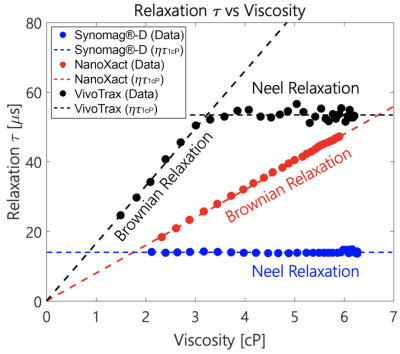

Determining the dominant relaxation mechanismWe performed square wave relaxometry on three commercial SPIO nanoparticles: micromod Synomag®-D, nanoComposix NanoXact, and Magnetic Insight VivoTrax to determine their dominant relaxation mechanisms. Viscous tracer solutions were prepared using aliquots of commercial SPIOs combined with glycerol in a 55-45 ratio (by weight). We generated the viscosity-temperature calibration curves using a heating mantle to heat the solutions to 65°C and cool them subsequently under ambient conditions to measure viscosity. Relaxation time constants of all 40 µL SPIO-glycerol solutions were measured using a periodic square-wave pulsed magnetic field of amplitude 6 mT and 1 kHz frequency in an Arbitrary Waveform Relaxometer (AWR) [12]. We integrated and fitted the gradiometric received signals to a rising exponential function to determine the relaxation time constant (Fig. 3 & 4).

Sensing cell viability

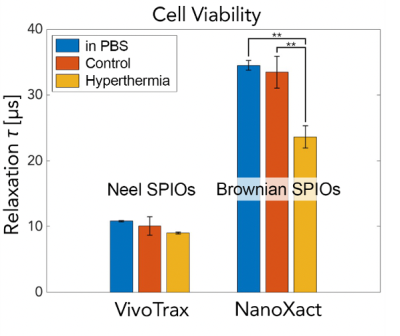

We used NanoXact and VivoTrax to label LLC1 lung cancer cells. Of the four flasks of cells, two were incubated with 100 µL of NanoXact and the other two with 300 µL of VivoTrax. After 24 hours, the cells were harvested and washed with a phosphate buffer. The NanoXact and VivoTrax labeled cells were divided into two groups. One group was incubated at 37°C (control), and the other group was incubated in a hot water bath at 60°C to induce cell death via hyperthermia for 2 hours. Relaxation time constants of both groups of cells were measured using a periodic square-wave pulsed magnetic field of amplitude 10 mT and 1 kHz frequency in the AWR. We integrated and fitted the gradiometric received signals to a rising exponential function to determine the relaxation time constant.

Results and Discussion

We observed distinct relaxation mechanisms in each of the commercial SPIOs (Fig. 4). Synomag®-D shows a Néelian behavior with no observable change in relaxation time constant as the tracer solution viscosity changes. NanoXact has a relaxation time that scales linearly with viscosity, exhibiting a Brownian behavior. VivoTrax relaxes in a Brownian manner up to 3 cP, after which the Néel relaxation mechanism dominates as the faster relaxation mechanism. There is no linear relationship between relaxation time and viscosity beyond 3 cP in VivoTrax.We also observed distinct relaxation mechanisms in the two groups of cells labeled with Brownian (NanoXact) and Néelian (VivoTrax) SPIOs (Fig. 5). As hypothesized, there are statistically significant (p<0.01) changes in Brownian relaxation due to viscosity changes in apoptotic cells. There is no change in relaxation time in cells labeled with Néelian SPIOs (VivoTrax). These data show great promise for MPI cell tracking using Brownian SPIOs to monitor therapeutic cell viability.

Conclusion

Nanoscale viscosity is challenging to measure in vivo. We have demonstrated that Brownian MPI relaxation is a new and unexplored tool for measuring viscosity changes during cell death. No other cell tracking tool (MRI, CT, X-ray or nuclear medicine) offers this unique cell viability sensing ability. In the future, we plan to exploit Brownian relaxation contrast to allow for distinguishing bound SPIOs (which will have restricted rotation) from unbound SPIOs in an imaging format. This remains an open challenge for medical imaging.Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge support from NIH grants R01s EB019458, EB024578, EB029822 and R44: EB029877, UC TRDRP grant 26IP-0049, M. Cook Chair, Bakar Fellowship, the Siebel fellowship, the UC Discovery Award, the Craven Fellowship from UC Berkeley Bioengineering, NSERC fellowship, as well as the NIH-T32 training and NSF fellowships.References

[1] M.-J. Gorbet and A. Ranjan, “Cancer immunotherapy with immunoadjuvants, nanoparticles, and checkpoint inhibitors: Recent progress and challenges in treatment and tracking response to immunotherapy,” Pharmacology & Therapeutics, vol. 207, p. 107 456, 2020;

[2] B. Zheng, T. Vazin, P. W. Goodwill, et al., “Magnetic particle imaging tracks the long-term fate of in vivo neural cell implants with high image contrast,” Sci. Rep., vol. 5, p. 14 055, Sep. 2015;

[3] X. Y. Zhou, K. E. Jeffris, E. Y. Yu, et al., “First in vivo magnetic particle imaging of lung perfusion in rats,” Phys. Med. Biol., vol. 62, no. 9, pp. 3510–3522, May 2017;

[4] E. Y. Yu, P. Chandrasekharan, R. Berzon, et al., “Magnetic Particle Imaging for Highly Sensitive, Quantitative, and Safe in Vivo Gut Bleed Detection in a Murine Model,” ACS Nano, vol. 11, no. 12, pp. 12 067–12 076, Dec. 2017;

[5] B. Zheng, M. P. von See, E. Yu, et al., “Quantitative magnetic particle imaging monitors the transplantation, biodistribution, and clearance of stem cells in vivo,” Theranostics, vol. 6, no. 3, pp. 291– 301, Mar. 2016;

[6] B. Zheng, E. Yu, R. Orendorff, et al., “Seeing SPIOs directly in vivo with magnetic particle imaging,” Mol. Imaging Biol., vol. 19, no. 3, pp. 385–390, Jun. 2017;

[7] X. Y. Zhou, Z. W. Tay, P. Chandrasekharan, et al., “Magnetic particle imaging for radiation-free, sensitive and high-contrast vascular imaging and cell tracking,” Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol., vol. 45, pp. 131–138, Aug. 2018;

[8] Z. W. Tay, P. Chandrasekharan, X. Y. Zhou, E. Yu, B. Zheng, and S. Conolly, “In vivo tracking and quantification of inhaled aerosol using magnetic particle imaging towards inhaled therapeutic monitoring,” Theranostics, vol. 8, no. 13, pp. 3676–3687, 2018;

[9] P. Chandrasekharan, C. Colson, KLB Fung, et al., "Monitoring outcome of hyperthermia treatment by measuring relaxation induced blurring with magnetic particle spectroscopy," in World Molecular Imaging Congress 2019, WMIS, 2019;

[10] W.T. Coffey, Y.P. Kalmykov, and J.T. Waldron, The Langevin Equation, 2nd ed., World Scientific, Singapore, 2004;

[11] W.F. Brown, Thermal fluctuations of a single-domain particle, J Appl Phys 1963; 34:1319-20;

[12] Tay, Z., Goodwill, P., Hensley, D. et al. “A High-Throughput, Arbitrary-Waveform, MPI Spectrometer and Relaxometer for Comprehensive Magnetic Particle Optimization and Characterization,” Sci Rep 6, 34180 (2016).

Figures