0879

White Matter Reactivity to Hemodynamic Stimuli: Insights from Dynamic and Maximal Cerebrovascular Reserve after Acetazolamide Provocation1Radiology, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 2Radiology, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, NY, United States, 3Neurology, New York University, New York, NY, United States, 4Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Emory University, Atlanta, GA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: White Matter, fMRI (resting state), Cerebrovascular reactivity

We explored cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) of white matter in patients with evidence for micro- and macrovascular disease using our previously described Blood Oxygen Level Dependent – acetazolamide paradigm. Subjects consistently demonstrated lower CVR in voxels with microangiopathic white matter when present in hemispheres with coexistent proximal, large-vessel steno-occlusive disease (SOD). The relationship of CVR values in normal appearing white matter and contralateral white matter lesions in patients with unilateral SOD is more complex and warrants further investigation.INTRODUCTION

Cerebrovascular reactivity (CVR) describes the adaptive capacity of the cerebral circulation to respond to declining perfusion pressures and neurovascular demand following hemodynamic provocation. CVR is heterogeneous and varies across tissues and pathological states1,2. White matter CVR is not well-understood and only sparsely studied3–5. Blood Oxygen Level Dependent (BOLD) signal following hemodynamic stimulus with acetazolamide (ACZ) may be used to measure CVR6,7. Herein, we studied CVR differences between microangiopathic white matter lesions and normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) in patients with chronic steno-occlusive disease (SOD) to quantify the interplay of angiographically-evident macrovascular stenoses and parenchymal indicators of systemic microvascular disease, hypothesizing additive effects at the intersection of the two as studied by fully dynamic maximal CVR (CVRmax) as recently reported8–11.METHODS

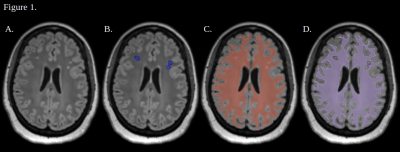

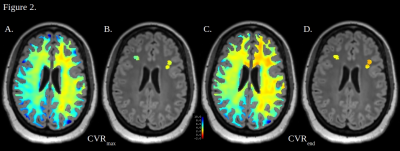

17 patients (11 unilateral, 3 bilateral with unilateral-predominant, and 3 bilateral) with angiographically-proven SOD were studied using our previously described dynamic BOLD-ACZ paradigm6. Briefly, 3-5 minutes of resting-state BOLD were followed, without interruption, by slow IV infusion (1g/3-4 minutes) of ACZ. BOLDpre and BOLDpost were defined as the average of the first and last minutes of the BOLD time-signal course (TSC), respectively. Conventional measures of terminal CVR at the exam conclusion (CVRend, i.e. %CVR=100*(BOLDpost–BOLDpre)/BOLDpre) and maximal CVR (CVRmax, i.e. maximal CVR per-voxel, per-TR, across the TSC) were computed from denoised BOLD data as previously reported8-11.White matter masks were generated from T1-weighted MPRAGE images with Freesurfer (version 7.1.1, Massachusetts General Hospital, MA)12. White matter lesion masks were generated manually in 3D Slicer13 via selection of discrete hyperintense lesions on FLAIR images, and NAWM masks were generated by subtraction of the two (Figure 1). Masks were applied to CVRmax and CVRend images with custom MATLAB scripts (version R2022b, The MathWorks, Natick, MA). Voxel-wise CVRmax and CVRend were calculated for NAWM and white matter lesions (Figure 2). In patients with unilateral disease or unilateral-predominant disease, four white matter subgroups were analyzed including: i. diseased hemisphere NAWM; ii. non-diseased hemisphere NAWM; iii. diseased hemisphere white matter lesions; and iv. non-diseased hemisphere white matter lesions. In patients with unilateral or unilateral-predominant disease, the diseased or most-diseased hemisphere is referred to as ipsilateral hemispheres and the opposite as contralateral. Statistical relationships between the four white matter groups within each subject were evaluated with a Kruskal-Wallis test with Bonferroni-corrected multiple comparisons in MATLAB. Statistical significance was set at 0.01.

RESULTS

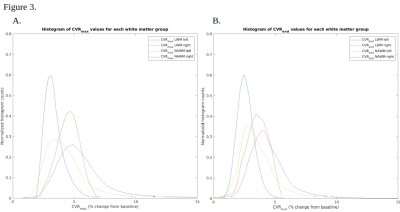

In patients with unilateral or unilateral-predominant hemispheric disease, 11/14 demonstrated the lowest CVRmax and CVRend values within the ipsilateral hemisphere white matter lesions, suggesting additive effects of microvascular and macrovascular disease. Two, among the discordant cases, exhibited only sporadic and small lesions affecting fidelity of lesion segmentation.In 7/14 subjects, the highest CVR values were observed within NAWM of the contralateral hemisphere, where neither evidence for macrovascular or microvascular injury was apparent. In 8/14 subjects, CVRmax and CVRend within the NAWM of the contralateral hemisphere was higher than the NAWM in the diseased hemisphere. In 11/14 subjects, the contralateral hemispheric white matter lesions demonstrated higher CVR than ipsilateral white matter lesions. Ipsilateral NAWM CVRmax and CVRend was lower than contralateral white matter lesions in 7/14 subjects.

Among the three patients with bilateral disease, two exhibited the lowest CVR values in white matter lesions of a given hemisphere; however, the lesional extent did not correlate with hemispheric CVR.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we describe the relationship between white matter CVR and the presence of macro- or microvascular indicators of disease. Subjects in this dataset consistently demonstrated lower CVR in voxels with microangiopathic disease when present in hemispheres with coexistent proximal, large-vessel SOD. Microangiopathic white matter in hemispheres with SOD consistently harbored the most abnormal voxels as defined by low-rank ordering of CVR values, corresponding to the microvascular disease in the ipsilateral (i.e. SOD) hemisphere, as expected. The relationship of CVR values in NAWM and contralateral white matter lesions is more complex and warrants further investigation. Further work will attempt to delineate the contributions of microvascular and macrovascular disease to CVR and whether segmentation of microangiopathic disease is required during CVR analysis.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Reich, T. & Rusinek, H. Cerebral cortical and white matter reactivity to carbon dioxide. Stroke 20, 453–457 (1989).

2. Marshall, O. et al. Impaired Cerebrovascular Reactivity in Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 71, 1275–1281 (2014).

3. Thomas, B. P., Liu, P., Park, D. C., van Osch, M. J. & Lu, H. Cerebrovascular reactivity in the brain white matter: magnitude, temporal characteristics, and age effects. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 34, 242–247 (2014).

4. Marstrand, J. r. et al. Cerebral Perfusion and Cerebrovascular Reactivity Are Reduced in White Matter Hyperintensities. Stroke 33, 972–976 (2002).

5. Sam, K. et al. Cerebrovascular reactivity and white matter integrity. Neurology 87, 2333–2339 (2016).

6. Wu, J., Dehkharghani, S., Nahab, F. & Qiu, D. Acetazolamide-augmented dynamic BOLD (aczBOLD) imaging for assessing cerebrovascular reactivity in chronic steno-occlusive disease of the anterior circulation: An initial experience. NeuroImage Clin. 13, 116–122 (2017).

7. Wu, J., Dehkharghani, S., Nahab, F., Allen, J. & Qiu, D. The Effects of Acetazolamide on the Evaluation of Cerebral Hemodynamics and Functional Connectivity Using Blood Oxygen Level–Dependent MR Imaging in Patients with Chronic Steno-Occlusive Disease of the Anterior Circulation. AJNR Am. J. Neuroradiol. 38, 139–145 (2017).

8. Dogra, S. et al. A Flexible Computational Framework for Characterization of Dynamic Cerebrovascular Response to Global Hemodynamic Stimuli. ISMRM (2021).

9. Dogra, S. et al. Revealing Occult Hemodynamic Signatures from the Acetazolamide-Augmented Cerebral BOLD Response. ISMRM (2022).

10. Dogra, S. et al. Diaschisis Profiles in the Cerebellar Response to Hemodynamic Stimuli: Insights from Dynamic Measurement of Cerebrovascular Reactivity to Identify Occult and Transient Maxima. In submission.

11. Dogra, S. et al. Demonstration of Crossed Cerebellar Diaschisis Using Dynamic BOLD-CVR. ISMRM (2023).

12. Fischl, B. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage 62, 774–781 (2012).

13. Fedorov, A. et al. 3D Slicer as an Image Computing Platform for the Quantitative Imaging Network. Magn. Reson. Imaging 30, 1323–1341 (2012).

Figures