0878

Multivariate analysis of perfusion and oxygenation patterns in asymptomatic unilateral carotid artery stenosis1Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Neuroradiology, School of Medicine, Technical University of Munich (TUM), Munich, Germany, 2MRRC, Department of Radiology & Biomedical Imaging, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States, 3Department of Neurology, School of Medicine, Technical University of Munich (TUM), Munich, Germany, 4Philips GmbH Market DACH, Hamburg, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Blood vessels, Oxygenation

Asymptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis (ICAS) is linked with increased stroke risk and cognitive decline. Physiological MRI of cerebral hemodynamic changes in ICAS patients is promising to inform treatment decisions. Here, we investigated the complex pathophysiology of ICAS using principal component analysis of cerebral perfusion and oxygenation changes to establish disease-specific patterns of CBF, OEF, CMRO2 and the effective oxygen diffusivity of the capillary bed. Regression models revealed the association of pattern expression with sonography-based degree of stenosis and flow velocity in the carotid artery, as well as systemic blood pressure.Introduction

Asymptomatic internal carotid artery stenosis (ICAS) is a prevalent condition in older individuals,1 which may cause stroke2 and cognitive decline.3,4 Taking cerebral hemodynamics into account to support treatment decisions has gained increasing interest5-9 and ICAS-induced impairments have been thoroughly investigated.9-14 Nevertheless, the pathophysiologic interplay between different parameters, such as cerebral blood flow (CBF), oxygen extraction fraction (OEF), cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen (CMRO2) and the effective oxygen diffusivity (EOD) of the capillary bed,15,16 still requires further characterization. Principal component analysis (PCA) has previously been employed to investigate hemodynamic networks in various conditions17-22 and, therefore, appears promising to foster understanding especially of diffuse perfusion or oxygenation changes in ICAS. Here, we aimed to derive ICAS-specific patterns of CBF, OEF, EOD and CMRO2 changes. We hypothesized associations of pattern expression in patients with two fundamental clinical ICAS markers, both measured by ultrasound: The stenosis degree according to NASCET23 and the maximum peak flow velocity (vmax) in the carotid artery. Additionally, the impact of systemic blood pressure was evaluated, as hypertension is both an important risk factor for ICAS24 and, independently, of downstream cerebrovascular dysfunction.25Methods

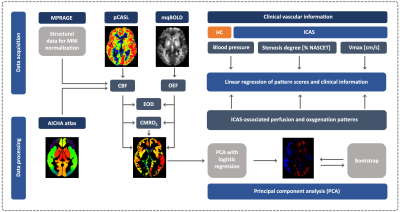

We scanned 24 unilateral ICAS patients (age 70.2±7.0y) and 28 healthy controls (HC, age 70.3±4.6y) on a 3T Philips Ingenia (Best, Netherlands). The imaging protocol (Fig.1) comprised MPRAGE for structural imaging, pseudo-continuous arterial spin labelling (pCASL)26 for CBF and multiparametric quantitative blood oxygen level dependent imaging (mqBOLD) for relative OEF.11,27,28 Images were MNI-normalized and flipped in left-sided patients. Mean parameter values were extracted from 384 VOIs using the AICHA atlas29 and used to calculate EOD and CMRO2. Following a previously described PCA approach,17,19,20,22 patterns were derived by combining disease-related principal components in a logistic regression model (Fig.1). Bootstrapping identified reliable areas.19 Additionally, absolute parameter values were calculated in areas with positive and negative loadings, as well as areas not surviving bootstrapping (Fig.2). Receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC) were obtained for network scores, parameter lateralization and global GM averages, and area under the curve (AUC) was used to compare their ability to separate ICAS patients from HC (Fig.3). Finally, regression analysis was used to evaluate the relationships of pattern scores with stenotic degree, vmax and blood pressure. For all statistical tests, significance was assumed for p<0.05.Results

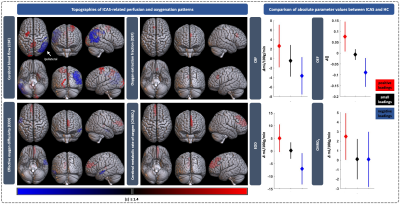

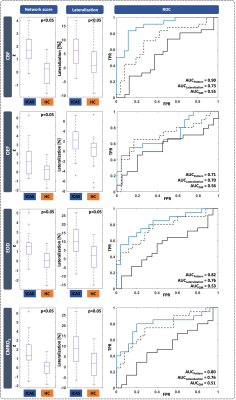

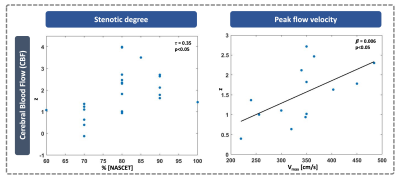

The CBF pattern included ipsilateral occipital/temporal negative loadings and predominantly contralateral positive loadings. EOD showed contralateral positive frontal and negative temporal loadings. OEF and CMRO2 patterns comprised contralateral positive loadings, but only one stable area for OEF. Comparing ICAS with HC, OEF and CMRO2 were elevated in areas of positive loadings, while OEF and EOD were decreased in areas of negative loadings (Fig.2). Patient scores on all patterns were significantly higher compared with HC (Fig.3). Hemispheric mean CBF, EOD and CMRO2 lateralization to the unaffected side was increased in patients, i.e., values were lower on the side of the stenosis (Fig.3). Discriminative ability of the PCA-pattern was highest in CBF and substantially stronger compared with lateralization of the hemispheric mean (AUCPattern=0.90,Fig.3), and strong for EOD and CMRO2 (AUCPattern=0.82/0.80). Linear regression of CBF scores with stenotic degree and vmax yielded positive associations (Fig.4). A multiple regression model accounting for age and sex identified higher systolic blood pressure as a significant predictor of EOD and CMRO2 scores (Fig.5). OEF network scores were not related with any of the clinical indicators.Discussion

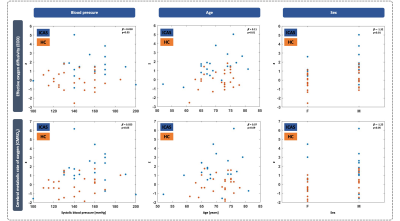

We employed PCA to derive ICAS-related patterns of CBF, OEF, EOD and CMRO2. The CBF network indicated bilateral involvement, potentially pointing to known effects from contralateral collateral flow.14,30 The pattern comprised ipsilateral relative hypoperfusion accompanied by contralateral relative increases, corresponding to perfusion lateralization as expected.10,11 Moreover, our analysis further localized these changes, resulting in increased AUC compared with interhemispheric lateralization (Fig.3). The characteristic OEF pattern was the topographically least stable, with only one area surviving bootstrapping (Fig.2). Consequently, it was less accurate in discriminating ICAS from HC (Fig.3, AUC=0.71), which is consistent with previous findings, that did not find major global OEF changes in ICAS.11,13 In contrast, EOD and CMRO2 patterns revealed changes primarily in the contralateral hemisphere, interestingly extending to areas not covered by the perfusion pattern. Findings included positive loadings for CMRO2, indicating elevated absolute CMRO2 in ICAS (Fig.2). Changes in EOD comprised both positive and negative loadings, which partially overlapped with elevated CMRO2 (Fig.2), implying local adjustments in capillary oxygen transport to support increased oxygen metabolism. Crucially, regression linking pattern scores to extracranial vascular changes, likely sources of the complex downstream cerebral hemodynamic impairments, support the pathophysiologic relevance of our analysis. Specifically, CBF network scores correlated with stenotic degree and vmax, i.e., more severe ICAS translated to stronger pattern expression (Fig.4). Furthermore, multiple regression, accounting for sex and age, linked systolic blood pressure to increased expression of the EOD and CMRO2 patterns (Fig. 5), possibly indicating damage at the capillary level, which is well-known to occur with hypertension.31 Consistent with largely unchanged OEF, its pattern was not associated with any of the clinical parameters.Conclusion

Our multivariate analysis revealed the characteristic regional changes that form ICAS-specific perfusion and oxygenation patterns. These patterns fostered deeper insights into the complex pathophysiological interplay between upstream vascular status and regional cerebral hemodynamics in ICAS.Acknowledgements

We acknowledge support by the Else-Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung (JK), Dr.-Ing. Leonhard-Lorenz-Stiftung (grant SK 971/19) and the German Research Foundation (DFG, grant PR 1039/6-1).References

1. de Weerd M, Greving JP, Hedblad B, et al. Prevalence of asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis in the general population: an individual participant data meta-analysis. Stroke 2010; 41: 1294-1297. 2010/05/01. DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.581058.

2. Petty GW, Brown RD, Jr., Whisnant JP, et al. Ischemic stroke subtypes: a population-based study of incidence and risk factors. Stroke 1999; 30: 2513-2516. 1999/12/03. DOI: 10.1161/01.str.30.12.2513.

3. Gottler J, Kaczmarz S, Nuttall R, et al. The stronger one-sided relative hypoperfusion, the more pronounced ipsilateral spatial attentional bias in patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2020; 40: 314-327. 2018/11/28. DOI: 10.1177/0271678X18815790.

4. Mathiesen EB, Waterloo K, Joakimsen O, et al. Reduced neuropsychological test performance in asymptomatic carotid stenosis: The Tromsø Study. Neurology 2004; 62: 695-701. 2004/03/10. DOI: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113759.80877.1f.

5. Marshall RS, Lazar RM, Liebeskind DS, et al. Carotid revascularization and medical management for asymptomatic carotid stenosis - Hemodynamics (CREST-H): Study design and rationale. Int J Stroke 2018; 13: 985-991. 2018/08/23. DOI: 10.1177/1747493018790088.

6. Schmitzer L, Sollmann N, Kufer J, et al. Decreasing Spatial Variability of Individual Watershed Areas by Revascularization Therapy in Patients With High-Grade Carotid Artery Stenosis. J Magn Reson Imaging 2021; 54: 1878-1889. 2021/06/20. DOI: 10.1002/jmri.27788.

7. Hino A, Tenjin H, Horikawa Y, et al. Hemodynamic and metabolic changes after carotid endarterectomy in patients with high-degree carotid artery stenosis. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis 2005; 14: 234-238. 2007/10/02. DOI: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2005.08.001.

8. Schroder J, Heinze M, Gunther M, et al. Dynamics of brain perfusion and cognitive performance in revascularization of carotid artery stenosis. Neuroimage Clin 2019; 22: 101779. 2019/03/25. DOI: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101779.

9. Soinne L, Helenius J, Tatlisumak T, et al. Cerebral hemodynamics in asymptomatic and symptomatic patients with high-grade carotid stenosis undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Stroke 2003; 34: 1655-1661. 2003/06/14. DOI: 10.1161/01.STR.0000075605.36068.D9.

10. Gottler J, Kaczmarz S, Kallmayer M, et al. Flow-metabolism uncoupling in patients with asymptomatic unilateral carotid artery stenosis assessed by multi-modal magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2019; 39: 2132-2143. 2018/07/04. DOI: 10.1177/0271678X18783369.

11. Kaczmarz S, Gottler J, Petr J, et al. Hemodynamic impairments within individual watershed areas in asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis by multimodal MRI. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2021; 41: 380-396. 2020/04/03. DOI: 10.1177/0271678X20912364.

12. Kaczmarz S, Griese V, Preibisch C, et al. Increased variability of watershed areas in patients with high-grade carotid stenosis. Neuroradiology 2018; 60: 311-323. 2018/01/05. DOI: 10.1007/s00234-017-1970-4.

13. Bouvier J, Detante O, Tahon F, et al. Reduced CMRO(2) and cerebrovascular reserve in patients with severe intracranial arterial stenosis: a combined multiparametric qBOLD oxygenation and BOLD fMRI study. Hum Brain Mapp 2015; 36: 695-706. 2014/10/14. DOI: 10.1002/hbm.22657.

14. Zarrinkoob L, Wahlin A, Ambarki K, et al. Blood Flow Lateralization and Collateral Compensatory Mechanisms in Patients With Carotid Artery Stenosis. Stroke 2019; 50: 1081-1088. 2019/04/05. DOI: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.119.024757.

15. Hyder F, Shulman RG and Rothman DL. A model for the regulation of cerebral oxygen delivery. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1998; 85: 554-564. DOI: 10.1152/jappl.1998.85.2.554.

16. Kufer J, Preibisch C, Epp S, et al. Imaging effective oxygen diffusivity in the human brain with multiparametric magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. Epub ahead of print 0271678x2110484. DOI: 10.1177/0271678x211048412.

17. Zhang N, Gordon ML, Ma Y, et al. The Age-Related Perfusion Pattern Measured With Arterial Spin Labeling MRI in Healthy Subjects. Front Aging Neurosci 2018; 10: 214. 2018/08/02. DOI: 10.3389/fnagi.2018.00214.

18. Asllani I, Habeck C, Scarmeas N, et al. Multivariate and univariate analysis of continuous arterial spin labeling perfusion MRI in Alzheimer's disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2008; 28: 725-736. 2007/10/26. DOI: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600570.

19. Habeck C, Foster NL, Perneczky R, et al. Multivariate and univariate neuroimaging biomarkers of Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage 2008; 40: 1503-1515. 2008/03/18. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.01.056.

20. Spetsieris PG, Ma Y, Dhawan V, et al. Differential diagnosis of parkinsonian syndromes using PCA-based functional imaging features. Neuroimage 2009; 45: 1241-1252. 2009/04/08. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.063.

21. Nobili F, Salmaso D, Morbelli S, et al. Principal component analysis of FDG PET in amnestic MCI. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2008; 35: 2191-2202. 2008/07/24. DOI: 10.1007/s00259-008-0869-z.

22. Melzer TR, Watts R, MacAskill MR, et al. Arterial spin labelling reveals an abnormal cerebral perfusion pattern in Parkinson's disease. Brain 2011; 134: 845-855. 2011/02/12. DOI: 10.1093/brain/awq377.

23. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial. Methods, patient characteristics, and progress. Stroke 1991; 22: 711-720. 1991/06/01. DOI: 10.1161/01.str.22.6.711.

24. Sutton-Tyrrell K, Alcorn HG, Wolfson SK, Jr., et al. Predictors of carotid stenosis in older adults with and without isolated systolic hypertension. Stroke 1993; 24: 355-361. 1993/03/01. DOI: 10.1161/01.str.24.3.355.

25. Iadecola C and Davisson RL. Hypertension and cerebrovascular dysfunction. Cell Metab 2008; 7: 476-484. 2008/06/05. DOI: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.03.010.

26. Alsop DC, Detre JA, Golay X, et al. Recommended implementation of arterial spin-labeled perfusion MRI for clinical applications: A consensus of the ISMRM perfusion study group and the European consortium for ASL in dementia. Magn Reson Med 2015; 73: 102-116. 2014/04/10. DOI: 10.1002/mrm.25197.

27. Hirsch NM, Toth V, Forschler A, et al. Technical considerations on the validity of blood oxygenation level-dependent-based MR assessment of vascular deoxygenation. NMR Biomed 2014; 27: 853-862. 2014/05/09. DOI: 10.1002/nbm.3131.

28. Kaczmarz S, Hyder F and Preibisch C. Oxygen extraction fraction mapping with multi-parametric quantitative BOLD MRI: Reduced transverse relaxation bias using 3D-GraSE imaging. Neuroimage 2020; 220: 117095. 2020/07/01. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117095.

29. Joliot M, Jobard G, Naveau M, et al. AICHA: An atlas of intrinsic connectivity of homotopic areas. J Neurosci Methods 2015; 254: 46-59. 2015/07/28. DOI: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2015.07.013.

30. Hoffmann G, Reichert M, Göttler J, et al. Perfusion territory shifts in asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis measured by super-selective arterial spin labelling. In: Proceedings of the 31st Annual Meeting of the ISMRM London, 2022.

31. Ostergaard L, Engedal TS, Moreton F, et al. Cerebral small vessel disease: Capillary pathways to stroke and cognitive decline. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2016; 36: 302-325. 2015/12/15. DOI: 10.1177/0271678X15606723.

Figures

Figure 1: Imaging protocol and principal component analysis (PCA). The MR protocol comprised MPRAGE, multiparametric quantitative BOLD (mqBOLD)27 and pseudo-continuous arterial spin labelling (pCASL).26 CBF, OEF, CMRO2 and effective oxygen diffusivity (EOD)15 mean values were extracted in grey matter VOIs using the AICHA atlas.29 PCA was applied to derive disease-related covariance patterns following a widely used approach.19,20 Pattern scores were correlated with clinical information.

Figure 2: Topography of ICAS-related hemodynamic patterns and comparison of absolute parameter values. Perfusion and oxygenation patterns are shown on the left. Only areas with positive (red) or negative (blue) loadings surviving the bootstrapping procedure are displayed. White arrow indicates side of stenosis. The right panel shows absolute, per-group mean parameter differences (diamonds) between ICAS patients and HC in areas with positive, negative and small, unstable loadings (black) with 95% confidence intervals (vertical lines).

Figure 3: Comparison of mean network score, interhemispheric lateralization and receiver operating characteristic curves (ROC). Mean pattern score (left) and interhemispheric lateralization (middle) of mean GM values were compared between ICAS and HC for each hemodynamic parameter using two-sample t-tests. Positive lateralization indicates higher values on left/unaffected side of HC/ICAS patients. ROCs (right) comparing discriminative ability of pattern score, lateralization and global mean GM.

Figure 5: Multiple regression for blood pressure, age and sex as predictors of EOD (top) and CMRO2 (bottom) network score. Blue dots correspond to an individual patient data, while orange dots indicate HC. A multiple linear regression model accounting for age (middle) and sex (right) was fit for EOD and CMRO2 to explore the relationship between systolic blood pressure (left) and pattern scores across ICAS and HC. Blood pressure and sex correlated with both, while age was significant only for EOD.