0875

The role of FK506 binding protein 5 in the early development of ischemic lesion using multi-parametric MRI1Department of Biomedical Imaging and Radiological Sciences, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei, Taiwan, 2Department and Institute of Physiology, College of Medicine, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei, Taiwan, 3Department of Medical Imaging and Radiological Sciences, College of Medicine, Chang Gung University, Taoyuan, Taiwan, 4partment of Medical Imaging and Intervention, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Linkou, Taoyuan, Taiwan, 5Brain Research Center, National Yang Ming Chiao Tung University, Taipei, Taiwan

Synopsis

Keywords: Stroke, Preclinical, Transgenic mice

To explore how the FK506 binding protein 5 (FKBP5) affect the ischemic stroke outcome, we employed Fkbp5-knock out (KO) mice and evaluated the ADC- and CBF-deficit volume, as well as angiography in the acute phase and the final lesion volume at 24 hours after the occlusion of middle cerebral artery (MCAO). The discent lesion volume and loss of collaterals after MCAO in the Fkbp5-KO animals suggested the early determination of the stroke outcome in the Fkbp5-KO animals after ischemic insult.Introduction

Ischemic stroke is the most common type of cerebral stroke, which may cause disability or even death.1 Various molecules by regulating the cerebral flow, collateral abundance, etc. have been reported to affect the stroke outcomes. FK506 binding protein 5 (FKBP5), a co-chaperone of glucocorticoid receptor (GR), is a member of the immunoaffinity protein family associated with several regulatory signaling pathways such as NFκB, AKT, and etc.2,3 It is acknowledged that the upregulation of FKBP5 increases the stress-related anxiety and depression by the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis.4 Lately, Shijia et al., reported the higher expression of FKBP5 in patients after ischemic stroke, and the levels of FKBP5 was positively correlated with severity.5 They also demonstrated by the over-expression of FKBP5, the cells may promote inflammation and autophagy after the depletion of oxygen and glucose, ultimately aggravating the cell death. However, the role of FKBP5 in intermediating the lesion growth or flow reperfusion after stroke was well explored yet. In this study, we compared the lesion outcomes in the wild-type (WT) with the Fkbp5-knock out (KO) mice from acute to chronic phase after permanent ischemic stroke. The dynamics of stroke lesion by diffusion and perfusion MRI may serve as evidence showing that the deletion of Fkbp5 gene may eliminate the compensatory flow soon after ischemic stroke.Methods

Thirteen male C57BL/6 mice including the wild-type (WT, n=7) and the Fkbp5 knock-out (Fkbp5-KO, n=6) were anesthetized with 1-2% isoflurane following by occlusion of the right middle carotid artery (MCAO)6 by a 6/O monofilament nylon suture. Longitudinal MRI scan on a Bruker 7T PharmaScan scanner was performed at 90, 120, 150, 180 minutes, and 24 hours after occlusion. T2-weighted images using a rapid acquisition with a relaxation enhancement sequence (TR/TE = 3000/30 ms, FOV = 15 × 15 mm2, matrix size = 200 × 200, RARE factor = 8, echo spacing = 7.5 ms, 12 slices, slice thickness = 0.75 mm) was acquired for anatomical information. Diffusion tensor images were acquired with the same geometry using the 4-shot spin-echo EPI with TR/TE = 3000/30 ms, matrix size = 96 × 96, δ/Δ = 5/15 ms, number of B0 = 5, number of directions = 30, b-value = 1000 s/mm2, number of averages = 2. Perfusion weighted images using dynamic susceptibility contrast with a series of one-shot gradient-echo EPI with the same geometry (TR/TE = 1000/20 ms, matrix size = 96 × 96, bandwidth = 184331.8 Hz, α = 90˚, number of repetitions = 300) was acquired by injection of Gadolinium (0.2 mmol/kg, i.v.) within 5 seconds. MRI 3D angiography without contrast agent using time of flight (TOF) sequence (TR/TE = 12/3 ms, matrix size = 256 × 256 × 96, number of averages = 4, α = 20˚) was also acquired. Tested Zea-Longa neurological deficit score at each time interval (0, no deficit; 1, dysfunction in stretching the left anterior limb; 2, walking clockwise or trying to climb its tail; 3, falling to contralateral side; 4, loss of gait) was performed7. All the animals were sacrificed at 24 hours after stroke for 2,3,5-Triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC) stain. Statistical analysis was performed using t-test and one-way ANOVA for between groups and longitudinal comparison, respectively (P<0.05).Results & Discussion

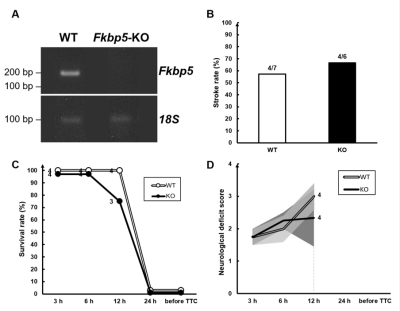

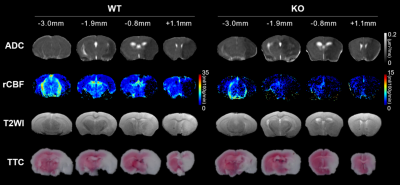

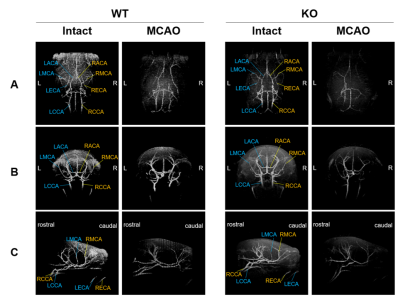

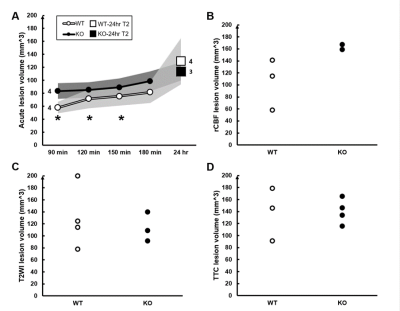

Reverse transcription PCR shows the absence of Fkbp5 mRNA in the Fkbp5-KO mice (Fig. 1A). No significant difference in stroke rate, survival rate, and neurological deficit score between the WT and Fkbp5-KO mice (Fig. 1B-D). Slightly larger infarct lesion size was found in the acute phase of stroke in the WT animals compared with that in the Fkbp5-KO mice. However, the lesion volume in T2-weighted images and TTC8 were quite similar in the WT and Fkbp5-KO mice (Fig. 2, Fig. 4C and D). Although complete circle of Willis was shown in both groups before surgery, less number of collateral vessels including the loss of both ipsilateral ACA and ECA was commonly observed after MCAO in the Fkbp5-KO mice (Fig. 3). Moreover, we defined the ADC- and CBF-deficit region in the acute phase after stroke.9 The volume of ischemic core indicated by ADC-deficit region within 150 minutes was significant smaller than the final lesion at 24 hours after stroke in the WT group (Fig. 4A). No significant changes in lesion volume after stroke was found in the Fkbp5-KO mice. Taken together with the larger CBF-deficit region in the Fkbp5-KO mice in the acute phase, we speculated that the loss of innate collateral circulation soon after stroke onset may determine the final stroke lesion at the subacute phase. Our future studies will focus on the comparison between the cerebral blood flow and the number of collaterals to explore impact on the degree of reperfusion after stroke by the knock-out of Fkbp5 gene.Acknowledgements

This study was funded in part by Ministry of Science and Technology (NSTC 111-2314-B-A49-086 and MOST 109-2314-B-010-067-MY3), Taipei,Taiwan.References

1. Lipton P. Ischemic cell death in brain neurons. Physiological Reviews. 1999;79(4):1431-1568.

2. L Li, Z Lou, Wang L. The role of FKBP5 in cancer aetiology and chemoresistance. British Journal of Cancer. 2011;104(1):19-23.

3. Gabriel R Fries, Nils C Gassen, Rein T. The FKBP51 Glucocorticoid Receptor Co-Chaperone: Regulation, Function, and Implications in Health and Disease. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2017;18(12):2614.

4. Yu‑Ling Gan, Chen‑Yu Wang, Rong‑Heng He, Pei‑Chien Hsu, Hsin‑Hsien Yeh, Tsung‑Han Hsieh, et al. FKBP51 mediates resilience to inflammation -induced anxiety through regulation of glutamic acid decarboxylase 65 expression in mouse hippocampus. Journal of Neuroinflammation. 2022;19(1):152.

5. Shijia Yu, Mingjun Yu, Zhongqi Bu, Feng PHaJ. FKBP5 Exacerbates Impairments in Cerebral Ischemic Stroke by Inducing Autophagy via the AKT/FOXO3 Pathway. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2020;14.

6. Terrance Chiang ROM, Wen-Hai Chou. Mouse Model of Middle Cerebral Artery Occlusion. Journal of Visualized Experiments. 2011(48):e2761.

7. Yanan Zhanga ZS, Yanling Zhaoa, Yanqiu Aia. Sevoflurane prevents miR-181a-induced cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Chemico-Biological Interactions. 2019;308:332-338.

8. Melissa Trotman-Lucas MEK, Justyna Janus, Robert Fern, Claire L. Gibson. An alternative surgical approach reduces variability following filament induction of experimental stroke in mice. The Company of Biologists. 2017(11):931-938.

9. Xiangjun Meng MF, Qiang Shen, Christopher H. Sotak, and Timothy Q. Duong. Characterizing the Diffusion/Perfusion Mismatch in Experimental Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Annals of Neurol. 2004;55(2):207-212.

Figures