0874

Microstructural and microvascular alterations in small vessel diseases using multi-shell DTI inside and outside white matter hyperintensities1Department of Radiology and Nuclear Medicine, School for Mental Health and Neuroscience, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, Netherlands, 2Department of Neurology, CARIM School for Cardiovascular Diseases, Maastricht University Medical Center, Maastricht, Netherlands, 3Brain Research Imaging Centre, Centre for Clinical Brain Sciences, UK Dementia Institute Centre at the University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, United Kingdom, 4Institute for Stroke and Dementia Research (ISD), University Hospital, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany

Synopsis

Keywords: Stroke, Stroke, small vessel disease

The pathophysiology underlying white matter hyperintensities (WMHs) and changes in perilesional white matter are not fully understood in cerebral small vessel disease (SVD). Using multi-shell diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), we studied the mean (parenchymal) diffusivity (MD) and microvascular perfusion (f) inside and outside WMHs in sporadic and monogenetic (CADASIL) SVDs. The microstructure (expressed by MD) was most damaged inside WMHs and extended beyond the WMHs. Furthermore, f was highest at the WMH border, decreased towards the WMH center, and decreased outside WMHs, possibly reflecting multiple SVD-related alterations in the microvasculature, such as dilated microvessels, capillary rarefaction, and reduced microvascular integrity.Introduction

White matter hyperintensities (WMH) are visible markers of cerebral small vessel disease (SVD)1. WMHs are assumed to be the ultimate consequence of microvascular dysfunction, leading to increased interstitial fluid, demyelination and/or axonal loss2. Diagnostic images give valuable information on the extent and location of WMHs, but not on their pathophysiology or the subtle brain tissue alterations beyond these lesions.Previous MRI studies have supported the concept of a WMH penumbra, i.e. tissue at risk for conversion to WMH, by demonstrating altered microstructural and microvascular changes in the perilesional normal-appearing white matter (NAWM) in aging subjects with and without cerebrovascular disease3-5. Moreover, diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) and post-mortem histopathology studies have revealed heterogeneity within WMHs in terms of demyelination and axonal loss4,6,7.

Using multi-shell DTI, both microstructural integrity and microvascular properties can be studied in vivo8-10. We propose to use the spatial profile of the multi-shell DTI measures inside and outside WMHs as a proxy to interpret the course of failing mechanisms in sporadic and monogenetic SVD (CADASIL; Cerebral Autosomal Dominant Arteriopathy with Subcortical Infarcts and Leukoencephalopathy) using data from the multicenter INVESTIGATE@SVDs study (ISRCTN 10514229).

Methods

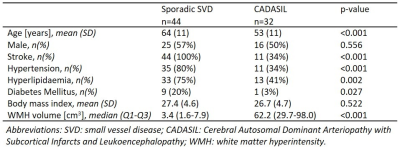

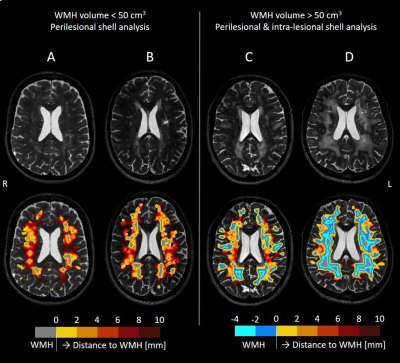

Patients: Among the 77 patients enrolled, 44 sporadic SVD and 32 CADASIL patients from the cross-sectional INVESTIGATE@SVDs study completed structural T2-weighted imaging and multi-shell DTI on 3T MRI (Siemens)11. Table 1 reports details of the study population.Image analysis: WMHs and NAWM were semi-automatically segmented12. For all patients, five 2-mm thick shells around the WMH were created in NAWM (Figure 1). Two additional 2-mm shells were created inside WMHs for patients with high WMH load (>50 cm3), as their high WMH volumes allowed for assessment of the spatial profile towards the center of WMH (Figure 1C-D).

Multi-shell DTI (2 mm cubic voxel size) included various b-values: b=0 (14 repetitions), 200 (3 directions), 500 (6 directions), 1000 s/mm2 (64 directions). The diffusion-weighted images were corrected for subject motion and echo-planar-imaging distortions. Accounting for intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM), the diffusion signal attenuation can be described as $$$S(b,\hat{g})/S(0)=(1-f)e^{-b\hat{g}^{T}\mathbf{\mathit{D}}\hat{g}}$$$ in the sampled b-value range, where D is the diffusion tensor, f is the signal fraction due to the fast microvascular pseudo-diffusion effect, and $$$\hat{g}$$$ is the diffusion-sensitizing direction8,9. This tensor model was fitted to the voxel-wise signal attenuation curves (Levenberg-Marquardt optimization) to obtain f and D maps. The mean diffusivity (MD) was derived from D. MD and f maps were spatially co-registered to the T2-weighed image space to obtain median MD and f values per shell.

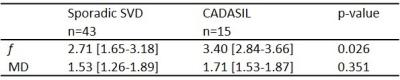

Statistics: Adjacent region-of-interests were compared using paired t-tests, separately for sporadic SVD with low WMH volume (<50 cm3) (n=43), CADASIL with low WMH volume (n=15), and CADASIL with high WMH volume (n=17). One sporadic SVD patient had high WMH volume (94 cm3). Exponential curve fitting (y=a+b·e-x/d) was performed in NAWM to express f and MD as function of distance to the WMH edge (x). The calculated characteristic WMH penumbra thickness (d) was compared between sporadic SVD and CADASIL patients with low WMH volumes, to focus on similar NAWM regions, using Mann-Whitney U tests.

Results

In sporadic SVD patients, f was lowest inside WMHs, highest in the first perilesional shell (0-2 mm distant to WMH edge), and decreased again up to a distance of 10 mm from the WMH edge (Figure 2-1A). A similar pattern was observed in CADASIL patients, although the penumbra of f was wider compared to sporadic SVD (p=0.012; Table 2), and no significant decrease in f was found at 6-10 mm from the WMH edge (Figure 2-1B).Both groups had an exponential decrease in MD values in NAWM more distant to the WMH border (Figure 2-2). MD increased inside WMH towards the WMH center (Figure 2-2D).

Discussion and conclusion

Our results show that multi-shell DTI can detect both microvascular (f) and microstructural (MD) abnormalities at the proximity of WMH and inside WMH. In our cross-sectional study design, the spatial path from remotely located NAWM to the WMH center may serve as a proxy for the time-course of the development of SVD pathology, which needs to be confirmed with longitudinal studies.The spatial profile of f across shells supports the idea that multiple changes occur during SVD pathogenesis affecting f in different ways2. For instance, dilated blood vessels compensating for impaired perfusion in perilesional zones might explain the increasing f in NAWM towards WMH, whereas the loss of blood vessels (capillary rarefaction) and decrease in blood flow (hypoperfusion) after WMH formation can explain the lower f inside WMH. Moreover, f might also be influenced by reduced microvascular integrity, e.g. blood-brain-barrier disruption2. The thicker WMH penumbra in CADASIL compared to sporadic SVD suggests that the NAWM is less quiescent, and could explain the greater longitudinal increases of SVD markers previously found in CADASIL13.

The progressive decrease of MD in NAWM with distance to the WMH edge indicates that microstructural alterations extend beyond WMH, which is in line with previous studies4,5,7. Furthermore, we demonstrated that the microstructure shows stronger deterioration towards the center of WMHs. This heterogeneous microstructural damage inside WMH may help unravel the balance of pathological processes and stages (e.g. fluid shifts and axonal loss) that underlie WMHs and provide information on disease progression14,15.

Acknowledgements

This work has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme ‘CRUCIAL’ under grant number 848109.

This project has received funding form the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme 'SVDs@target' under grant number 666881.

References

1. Wardlaw JM, Smith EE, Biessels GJ, Cordonnier C, Fazekas F, Frayne R, et al. Neuroimaging standards for research into small vessel disease and its contribution to ageing and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(8):822-38.

2. van Dinther M, Voorter PH, Jansen JF, Jones EA, van Oostenbrugge RJ, Staals J, et al. Assessment of microvascular rarefaction in human brain disorders using physiological magnetic resonance imaging. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2022;41(11):1-20.

3. Wong SM, Jansen JF, Zhang CE, Hoff EI, Staals J, van Oostenbrugge RJ, et al. Blood-brain barrier impairment and hypoperfusion are linked in cerebral small vessel disease. Neurology. 2019;92(15):e1669-e77.

4. Ferris JK, Greeley B, Vavasour IM, Kraeutner SN, Rinat S, Ramirez J, et al. In vivo myelin imaging and tissue microstructure in white matter hyperintensities and perilesional white matter. Brain Commun. 2022;4(3):fcac142.

5. Wardlaw JM, Makin SJ, Hernández MCV, Armitage PA, Heye AK, Chappell FM, et al. Blood-brain barrier failure as a core mechanism in cerebral small vessel disease and dementia: evidence from a cohort study. Alzheimers Dement. 2017;13(6):634-43.

6. Gouw AA, Seewann A, van der Flier WM, Barkhof F, Rozemuller AM, Scheltens P, et al. Heterogeneity of small vessel disease: a systematic review of MRI and histopathology correlations. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011;82(2):126-35.

7. Maniega SM, Hernández MCV, Clayden JD, Royle NA, Murray C, Morris Z, et al. White matter hyperintensities and normal-appearing white matter integrity in the aging brain. Neurobiol Aging. 2015;36(2):909-18.

8. Vieni C, Ades-Aron B, Conti B, Sigmund EE, Riviello P, Shepherd TM, et al. Effect of intravoxel incoherent motion on diffusion parameters in normal brain. Neuroimage. 2020;204:116228.

9. Mozumder M, Beltrachini L, Collier Q, Pozo JM, Frangi AF. Simultaneous magnetic resonance diffusion and pseudo‐diffusion tensor imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2018;79(4):2367-78.

10. Wong SM, Zhang CE, van Bussel FC, Staals J, Jeukens CR, Hofman PA, et al. Simultaneous investigation of microvasculature and parenchyma in cerebral small vessel disease using intravoxel incoherent motion imaging. NeuroImage Clin. 2017;14:216-21.

11. Blair GW, Stringer MS, Thrippleton MJ, Chappell FM, Shuler K, Hamilton I, et al. Imaging neurovascular, endothelial and structural integrity in preparation to treat small vessel diseases. The INVESTIGATE-SVDs study protocol. Part of the SVDs@ Target project. Cerebral Circulation-Cognition and Behavior. 2021;2:100020.

12. Valdés Hernández MdC, González-Castro V, Ghandour DT, Wang X, Doubal F, Muñoz Maniega S, et al. On the computational assessment of white matter hyperintensity progression: difficulties in method selection and bias field correction performance on images with significant white matter pathology. Neuroradiology. 2016;58(5):475-85.

13. Yoon CW, Kim Y-E, Kim HJ, Ki C-S, Lee H, Rha J-H, et al. Comparison of Longitudinal Changes of Cerebral Small Vessel Disease Markers and Cognitive Function Between Subcortical Vascular Mild Cognitive Impairment With and Without NOTCH3 Variant: A 5-Year Follow-Up Study. Front Neurol. 2021;12:586366.

14. Wardlaw JM, Valdés Hernández MC, Muñoz-Maniega S. What are white matter hyperintensities made of? Relevance to vascular cognitive impairment. Journal of the American Heart Association 2015;4(6):001140.

15. Jochems AC, Arteaga C, Chappell F, Ritakari T, Hooley M, Doubal F, et al. Longitudinal changes of white matter hyperintensities in sporadic small vessel disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2022.

Figures