0866

Alternating Low-Rank Tensor Reconstruction for Improved Multi-Dimensional MRI with MR Multitasking1Cedars Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, CA, United States, 2University of California, Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Sparse & Low-Rank Models, Sparse & Low-Rank Models

Low-rank tensor modelling is promising for multi-dimensional MR imaging. In this work, we developed a new low-rank tensor reconstruction approach using alternating minimization of spatial and temporal bases from the whole k-t space data instead of from split subsets of data. The approach was evaluated for 2D motion-resolved myocardial T1/T2/T2*/fat-fraction mapping and could potentially be used for imporving reconstruction quality and/or further reducing scan time.Introduction

Multi-dimensional MRI has drawn increasing attention1-3. Tensor and array modeling are crucial in enabling highly accelerated acquisition by leveraging sparsity and/or image correlations4-6. For example, MR Multitasking framework5 models underlying images as a low-rank tensor, first determining a temporal subspace from auxiliary navigator data, then performing subspace-constrained reconstruction of spatial coefficient maps from separate k-t space data.However, neither step of this workflow is performed from the complete acquired data, potentially introducing subspace bias, especially at high undersampling rates. With the goal of improving reconstruction quality and further reducing scan time, we propose a new image reconstruction algorithm for MR Multitasking which estimates both the temporal subspace and spatial coefficients from the complete acquired data. We evaluated this algorithm for 2D myocardial T1/T2/T2*/fat-fraction (FF) mapping7, in a numerical phantom and in-vivo.

Methods

Image acquisitionData were acquired using an interleaved scheme7: single-echo navigator data were repeatedly acquired at k-space center line to collect temporally rich information and multi-echo radial imaging data were acquired with golden angle increments for spatial information.

Image reconstruction

The underlying image series at the $$$p^{th}$$$ echo is modeled as a low-rank tensor with Tucker decomposition8, 9:

$$\mathcal{A}^{(p)}=\mathcal{G} \times_1 \mathbf{U}^{(1), p} \times_2 \mathbf{U}^{(2)} \times_3 \mathbf{U}^{(3)} \times_4 \mathbf{U}^{(4)} \times_5 \mathbf{U}^{(5)},\tag{1}$$

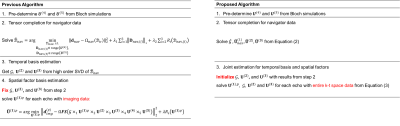

Where $$$\mathbf{U}^{(1),p}$$$ is the spatial basis for the $$$p^{th}$$$ echo, $$$\mathbf{U}^{(2)}$$$ and $$$\mathbf{U}^{(3)}$$$ are the cardiac and respiratory motion bases, and $$$\mathbf{U}^{(4)}$$$ and $$$\mathbf{U}^{(5)}$$$ are the pre-computed basis functions for T1&T2 relaxation. In previous Multitasking implementations7, 1) $$$\mathcal{G}$$$, $$$\mathbf{U}^{(2)}$$$, and $$$\mathbf{U}^{(3)}$$$ were first determined solely from the single-echo navigator data, via nuclear-norm based low-rank tensor completion and high-order SVD; 2) spatial factors $$$\mathbf{U}^{(1),p}$$$ were then estimated solely from the multi-echo imaging data with all temporal components fixed.

In this work, we improved both reconstruction steps, as shown in Fig. 1: 1) $$$\mathcal{G}$$$, $$$\mathbf{U}^{(2)}$$$, and $$$\mathbf{U}^{(3)}$$$ were initialized (but not fixed) from the navigator data using explicit rank constraints and alternating minimization, i.e.:

$$\begin{aligned}&\hat{\mathcal{G}}, \widehat{\mathbf{U}}_{\text {nav}}^{(1)}, \widehat{\mathbf{U}}^{(2)}, \widehat{\mathbf{U}}^{(3)} \\&=\arg \min _{\mathcal{G}, \mathbf{U}_{\text {nav }}^{(1)}, \mathbf{U}^{(2)}, \mathbf{U}^{(3)}} \| \mathbf{d}_{\text {nav }} \\&-\Omega_{\text {nav }}\left(\mathcal{G}\times_1 \mathbf{U}_{\text {nav }}^{(1)} \times_2 \mathbf{U}^{(2)} \times_3 \mathbf{U}^{(3)} \times_4 \mathbf{U}^{(4)} \times_5 \mathbf{U}^{(5)}\right) \|_2^2+\lambda \sum_{i=2}^3 R_{\mathrm{t}}\left(\left(\mathcal{G} \times_1 \mathbf{U}_{\text {nav}}^{(1)} \times_2 \mathbf{U}^{(2)} \times_3 \mathbf{U}^{(3)} \times_4 \mathbf{U}^{(4)} \times_5 \mathbf{U}^{(5)}\right){ }_{(i)}\right)\end{aligned}\tag{2}$$

where $$$d_{nav}$$$ is the acquired navigator data, $$$\Omega_{\text {nav }}(\cdot)$$$ is the sampling operator, $$$(\cdot)_{(i)}$$$ is the mode-$$$i$$$ unfolding of a tensor and $$$R_{\mathrm{t}}(\cdot)$$$ imposes total variation regularization for motion. 2) temporal factors $$$\mathcal{G}$$$, $$$\mathbf{U}^{(2)}$$$, and $$$\mathbf{U}^{(3)}$$$ and spatial factors $$$\mathbf{U}^{(1),p}$$$ were updated and calculated from the entire k-t space data through alternating least-squares minimization:

$$\hat{\mathcal{G}}, \widehat{\mathbf{U}}^{(1), \mathbf{p}}, \widehat{\mathbf{U}}^{(2)}, \widehat{\mathbf{U}}^{(3)}=\arg \min _{\mathcal{G}, \mathbf{U}^{(1), p}, \mathbf{U}^{(2)}, \mathbf{U}^{(3)}} \left\|\mathbf{d}^{(\mathbf{p})}-\Omega \mathbf{F} \mathbf{S}\left(\mathcal{G} \times_1 \mathbf{U}^{(1), \mathbf{p}} \times_2 \mathbf{U}^{(2)} \times_3 \mathbf{U}^{(3)} \times_4 \mathbf{U}^{(4)} \times_5 \mathbf{U}^{(5)}\right)\right\|_2^2 +\lambda R_{\mathrm{S}}\left(\mathbf{U}^{(1), \mathbf{p}}\right),\tag{3} $$

where $$$\mathbf{d}^{(\mathbf{p})}$$$ is the entire k-space data for $$$p^{th}$$$ echo, $$$\mathbf{F}$$$ is the Fourier sampling operator, $$$\mathbf{S}$$$ denotes sensitivity maps, and $$$R_{\mathrm{s}}(\cdot)$$$ is a wavelet sparsity regularizer.

Numerical simulations

A numerical phantom was created from XCAT phantom10 with 20 cardiac phases for each of the 6 respiratory phases. The sequence diagram and acquisition scheme shown in previous work7 was used and typical T1/T2/T2*/FF values at 3T were assigned. The average heart and respiration rates were set as 75 bpm and 15 bpm, respectively, with 10% standard deviation.

In-vivo study

One healthy volunteer was consented and scanned on a 3T scanner (MAGNETOM Vida, Siemens) at the mid-ventricular slice with an 18-channel body coil.

Analysis

All reconstructions were performed at two different scan times (2.5min and 1.5min) to test their performances at different acceleration factors. RMSE was used to evaluate the images from numerical simulations. For in-vivo maps, myocardium was segmented based on the AHA 16-segment model. The intra-segment average and standard deviation (SD) were compared between different approaches using two-way ANOVA test (N= 12, with 6 segments and 2 scan times).

Results

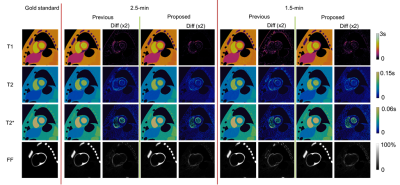

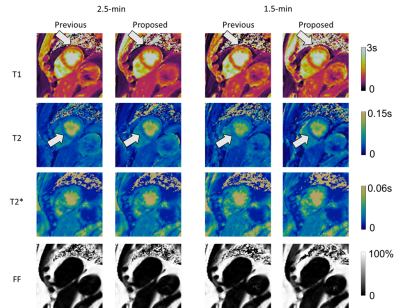

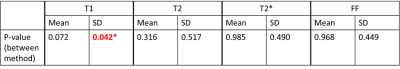

Fig. 2 shows the reconstructed parametric maps and the difference maps (x2) against gold standard. Lower residuals were seen in maps generated from the proposed approach than those from the previous approach. Table 1 shows that the proposed approach substantially reduces T1 and T2 map error at both scan times, and better maintains performance when reducing scan time from 2.5-min to 1.5-min. T2* and FF maps also show small improvements in all but one case.The in-vivo results are shown in Fig. 3. There is a visual quality improvement in myocardial homogeneity with the proposed approach, as pointed out by the arrows. The results of two-way ANOVA are summarized in Table 2, where a significant reduction is found in intra-segment SD (92 ms vs. 135 ms) of T1 with the proposed approach. No significant difference was found for other parameters.

Discussion and Conclusion

In this work, we developed a new approach for low-rank tensor reconstruction, which employed explicit rank constraints and provided flexibility for simultaneous updates of spatial and temporal basis. The approach can be seen as an extension of matrix recovery algorithm PowerFactorization11 for tensor recovery. Validation was performed with numerical simulations and a human subject, and the results indicated the potential for improving image quality and/or reducing scan time. Although Multitasking data was used, the approach should generalize to other low-rank tensor MRI methods. Further in-vivo validations are warranted.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (Grant/Award Nos. R01EB028146 and R01HL156818).References

1. He J, Liu Q, Christodoulou AG, Ma C, Lam F, Liang Z-P. Accelerated high-dimensional MR imaging with sparse sampling using low-rank tensors. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. Sep 2016;35(9):2119-2129. doi:10.1109/Tmi.2016.2550204

2. Yaman B, Weingartner S, Kargas N, Sidiropoulos ND, Akcakaya M. Low-Rank Tensor Models for Improved Multi-Dimensional MRI: Application to Dynamic Cardiac T1 Mapping. IEEE Trans Comput Imaging. 2019;6:194-207. doi:10.1109/tci.2019.2940916

3. Ma D, Gulani V, Seiberlich N, et al. Magnetic resonance fingerprinting. Nature. Mar 14 2013;495(7440):187-192. doi:10.1038/nature11971

4. Feng L, Axel L, Chandarana H, Block KT, Sodickson DK, Otazo R. XD-GRASP: Golden-Angle Radial MRI with Reconstruction of Extra Motion-State Dimensions Using Compressed Sensing. Magn Reson Med. Feb 2016;75(2):775-788. doi:10.1002/mrm.25665

5. Christodoulou AG, Shaw JL, Nguyen C, et al. Magnetic resonance multitasking for motion-resolved quantitative cardiovascular imaging. Nat Biomed Eng. Apr 2018;2(4):215-226. doi:10.1038/s41551-018-0217-y

6. Bustin A, Lima da Cruz G, Jaubert O, Lopez K, Botnar RM, Prieto C. High-dimensionality undersampled patch-based reconstruction (HD-PROST) for accelerated multi-contrast MRI. Magn Reson Med. Jun 2019;81(6):3705-3719. doi:10.1002/mrm.27694

7. Cao T, Wang N, Kwan AC, et al. Free-breathing, non-ECG, simultaneous myocardial T1, T2, T2*, and fat-fraction mapping with motion-resolved cardiovascular MR multitasking. Magn Reson Med. Oct 2022;88(4):1748-1763. doi:10.1002/mrm.29351

8. Kolda TG, Bader BW. Tensor Decompositions and Applications. Siam Rev. Sep 2009;51(3):455-500. doi:10.1137/07070111x

9. Tucker LR. Some mathematical notes on three-mode factor analysis. Psychometrika. Sep 1966;31(3):279-311. doi:10.1007/BF02289464

10. Segars WP, Sturgeon G, Mendonca S, Grimes J, Tsui BM. 4D XCAT phantom for multimodality imaging research. Med Phys. Sep 2010;37(9):4902-15. doi:10.1118/1.3480985

11. Vidal R, Tron R, Hartley R. Multiframe motion segmentation with missing data using PowerFactorization and GPCA. Int J Comput Vision. Aug 2008;79(1):85-105. doi:10.1007/s11263-007-0099-z

Figures