0859

K2S Challenge: From Undersampled K-Space to Automatic Segmentation

Aniket Tolpadi1, Upasana Bharadwaj1, Kenneth Gao1, Rupsa Bhattacharjee1, Felix Gassert1, Johanna Luitjens1, Jan Nikolas Morshuis2,3, Paul Fischer2, Matthias Hein2, Christian F. Baumgartner2, Artem Razumov4, Dmitry Dylov4, Quintin van Lohuizen5, Stefan Fransen5, Xiaoxia Zhang6, Radhika Tibrewaka6, Hector Lise de Moura6, Kangning Liu6, Marcelo Zibetti6, Ravinder Regatte6, Sharmila Majumdar1, and Valentina Pedoia1

1Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, UCSF, San Francisco, CA, United States, 2Cluster of Excellence Machine Learning, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany, 3International Max Planck Research School for Intelligent Systems, Tübingen, Germany, 4Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, Moscow, Russian Federation, 5Department of Radiology, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands, 6Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

1Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, UCSF, San Francisco, CA, United States, 2Cluster of Excellence Machine Learning, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany, 3International Max Planck Research School for Intelligent Systems, Tübingen, Germany, 4Skolkovo Institute of Science and Technology, Moscow, Russian Federation, 5Department of Radiology, University Medical Center Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands, 6Center for Advanced Imaging Innovation and Research, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, NY, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, MSK

Image reconstruction and downstream tasks have typically been treated independently by the image processing community, but we hypothesized performing them end-to-end could facilitate further optimization. To these ends, UCSF organized the K2S challenge, where challenge participants were tasked with segmenting bone and cartilage from 8X undersampled knee MRI acquisitions. Top challenge submissions produced high-quality segmentations maintaining fidelity to ground truth, but strong reconstruction performance proved not to be required for accurate tissue segmentation, and there was no correlation between reconstruction and segmentation performance. This challenge showed reconstruction algorithms can be optimized for downstream tasks in an end-to-end fashion.INTRODUCTION

In knee joint degenerative imaging, MRI has become the modality of choice, with acquisition time reduction and development of postprocessing techniques to extract information from scans emerging as research directions. Thus far, image reconstruction and postprocessing algorithms have been developed independently with few exceptions1. For reconstruction, algorithms predict full-length acquisition image appearance from undersampled k-space and are generally optimized for standard metrics: normalized root mean square error (nRMSE)2, peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR)3, and structural similarity index (SSIM)4. Although these metrics have limited correspondence to radiologist annotations5, perceptual correspondence with fully sampled images has made them metrics of choice when evaluating reconstruction algorithms—namely, they are often optimized for because reconstructed images are intended for human interpretation. If reconstruction and postprocessing were instead viewed as an end-to-end pipeline, reconstructed images would be features for subsequent algorithm input rather than human viewing, possibly leaving additional room for downstream task optimization. This was the rationale behind the K2S challenge, hosted by UCSF researchers at the 25th International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention (MICCAI), in which challenge participants were tasked with segmenting bone and cartilage from 8X undersampled MRIs.METHODS

Image Acquisition3D-Fast-Spin-Echo fat suppressed CUBE images were acquired at a UCSF GE Signa 3T MRI scanner, and an in-house pipeline was developed that leveraged GE Orchestra 1.10 to reconstruct images from raw scanner data and store multicoil k-space. Acquisition parameters were as follows: FOV=15cm2; acquisition matrix=256×256×200; ±62.5kHz readout bandwidth; TR=1002ms; TE=29ms; ARC acceleration by a factor of 46.

Ground Truth Segmentations

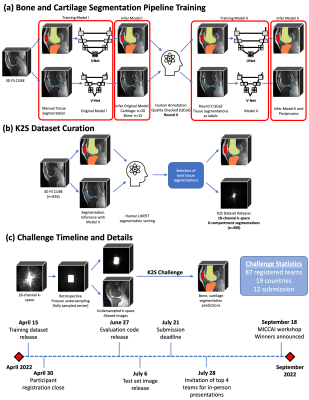

A 5-class 3D V-Net pipeline was trained to segment patellar, femoral and tibial cartilage7, while a 2D UNet pipeline was trained to segment the patella, femur and tibia8. Predicted segmentations were postprocessed and graded for quality by in-house radiologists using a 5-point LIKERT scale. Volumes with the top 350 segmentation scores across bone and cartilage were selected for the K2S dataset, with the corresponding radiologist-approved segmentations being designated as ground truth (Fig. 1).

K2S Challenge

On April 15, the K2S training dataset of 300 ARC-reconstructed fully sampled k-space, segmentations, and 8X center-weighted Poisson undersampling mask with a fully sampled 5% central square in ky-kz was released. Challenge participant recruitment ended April 30, with 87 teams registering. The test set of 8X undersampled k-spaces (n=50) was released July 6, with 12 submissions received (Fig. 1). Submissions were evaluated using a weighted sum of the dice similarity coefficient (DSC)9 for each of the 6 tissue compartments, where compartment weightings were inversely proportional to tissue size. Submissions from the top 4 teams were analyzed further, and each was asked to submit reconstructed image intermediates from their pipelines for additional analysis.

Top Submissions

K-nirsh pretrained separate 3D nn-UNet architectures10 that reconstructed coil-combined images from zero-filled coil-combined image space inputs, and segmented bone and cartilage. These pretrained architectures were then fine-tuned end-to-end, using a loss function scheduler that gradually increased the cartilage segmentation loss penalty. UglyBarnacle implemented a compressed sensing approach with combined total variation and L1-wavelet regularization to reconstruct undersampled images, and a UNet-style architecture to segment reconstructed images. FastMRI-AI used zero-filled root sum-of-squares coil-combined initializations as input for a 3D Single-Attention UNet11 which was trained for segmentation in a patch-based approach, affording cartilage double the weight of bone in the loss function. Finally, NYU-Knee AI trained a variational network to reconstruct coil-combined images from multicoil undersampled inputs and trained separate UNets to segment bone and cartilage from reconstructed images.

RESULTS

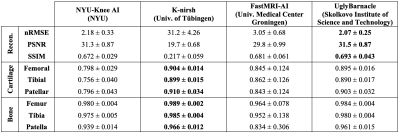

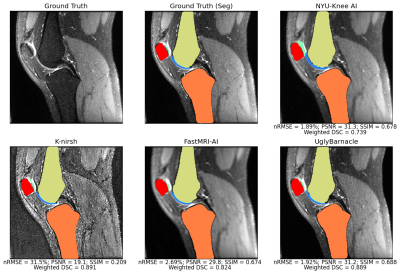

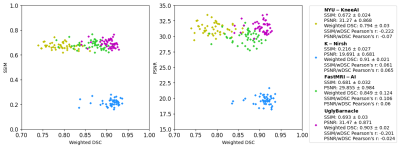

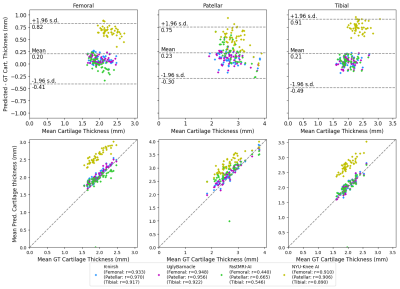

Segmentation performances and reconstruction metrics are in Fig. 2: K-nirsh had the best segmentation each tissue compartment, but interestingly, the poorest reconstruction metrics. Fig. 3 shows reconstructions and overlaid segmentations for an example patient, confirming the discordance between reconstruction and segmentation performance. Furthermore, plots of weighted DSC against SSIM and PSNR on a per-volume basis in Fig. 4 show essentially no correlation between reconstruction and segmentation performance the top submissions.Cartilage thickness was calculated on a per-patient basis for ground truth and submissions12 to assess the viability of submitted segmentations for biomarker analysis. 3 of the top submissions showed strong correlations between predicted and ground truth cartilage thickness while Bland-Altman plots showed 3 of the top submissions to exhibit essentially no bias in predicted cartilage thicknesses (Fig. 5).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSIONS

From the top 4 submissions, cartilage and bone segmentation quality was strong, yielding high DSCs for the 6 tested tissue compartments. Interestingly, strong intermediate pipeline reconstructions were not prerequisites for high-quality segmentation—the top-performing segmentation pipeline had the poorest reconstruction metrics, demonstrating the features desired for human interpretation can differ substantially from those optimal for subsequent algorithm processing. Biomarker analysis in assessing correlations of cartilage thickness between submissions and ground truth showed, however, UglyBarnacle had slightly higher correlations than K-nirsh in femoral and tibial cartilage despite slightly lower segmentation DSCs, illuminating further room for task-specific optimization.Reconstruction and postprocessing pipelines have largely been viewed independently, but this challenge shows room for optimization when they are viewed as an end-to-end task. Future work can include similar end-to-end optimization for tasks such as anomaly detection, prognosis prediction, and others directly from undersampled k-space.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Bruno Astuto Arouche Nunes for developing the multiclass knee cartilage and menisci segmentation pipeline. We acknowledge Andrew Leynes for developing a script that was adapted to automatically transfer raw scanner data from the 3T GE Sigma Scanners to local file systems. We also acknowledge Misung Han and Emma Bahroos for optimizing the FS CUBE sequence acquisition parameters used in this story. Furthermore, we acknowledge Leynes, Jon Tamir, Nikhil Deveshwar, and Peder Larson for assistance in selecting undersampling patterns to use for training algorithms. Additionally, we acknowledge Peter Storey, Jed Chan, Warren Steele, Rhett Hillary, Adam Stowe, and Scott Matsubayashi for their assistance in developing an infrastructure we could to host the considerable amount of data we made available for this challenge, and for developing a system challenge participants could use to gain access to the data. Lastly, we acknowledge Amy Becker for assistance in creating and maintaining the website for the K2S challenge. We thank MICCAI for giving us the opportunity to host this challenge and workshop at the 2022 conference in Singapore. Finally, we also would like to acknowledge our funding source NIH R01AR078762.References

- Calivà F et al. Breaking Speed Limits with Simultaneous Ultra-Fast MRI Reconstruction and Tissue Segmentation. PMLR. 2020;121:94-110.

- Fienup JR. Invariant error metrics for image reconstruction. Applied Optics. 1997;36:8352-7.

- Horé A, Ziou D. Is there a relationship between peak-signal-to-noise ratio and structural similarity index? IET Image Processing. 2013;7:12-24.

- Wang Z et al. Image Quality Assessment: From Error Visibility to Structural Similarity. In IEEE Trans Image Process. 2004;13:600-12.

- Mason A et al. Comparison of Objective Image Quality Metrics to Expert Radiologists’ Scoring of Diagnostic Quality of MR Images. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2020;39:1064-1072.

- Brau AC et al. Comparison of reconstruction accuracy and efficiency among autocalibrating data‐driven parallel imaging methods. Magn Reson Med. 2008;59:382-395.

- Nunes BAA et al. MRI-based multi-task deep learning for cartilage lesion severity staging in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2019;27:S398-99. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joca.2019.02.399.

- Ronneberger O, Fischer P, Brox T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. Medical Image Computating and Computer-Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2015. 2015;9351. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-24574-4_28.

- Eelbode, T et al. Optimization for Medical Image Segmentation: Theory and Practice When Evaluating With Dice Score or Jaccard Index. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2020;39:3679-3690. doi: 10.1109/TMI.2020.3002417.

- Isensee F et al. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nature Methods. 2020;18:203-11.

- Saha A, Zhang Y, Satapathy SC. Brain Tumour Segmentation with a Muti-Pathway ResNet Based UNet. Journal of Grid Computing. 2021;19:43.

- Iriondo C et al. Towards understanding mechanistic subgroups of osteoarthritis: 8-year cartilage thickness trajectory analysis. J Orthop Res. 2021;39:1305-1317. doi: 10.1002/jor.24849.

Figures

Fig. 1: Scans were curated and reconstructed using an in-house pipeline that saved raw k-space data, and ground truth segmentations generated by (a) training a 3D V-Net and 2D UNet to segment cartilage and bone, respectively, and postprocessing with morphological opening and connected components; (b) inferring models on potential cases and using radiologist assessments of segmentation quality to select volumes for inclusion in K2S (300 training, 50 test). The challenge timeline is shown in (c), as teams were tasked with segmenting bone and cartilage from 8X undersampled k-space.

Fig. 2: Reconstruction metrics and dice similarity coefficient (DSC) calculated for the top 4 submissions in the test set, all displayed mean ± 1 standard deviation (n=50), with top metrics bolded for all. Importantly, strong reconstruction performance was not the challenge objective, but the approach with the best segmentation performance also had by far the poorer reconstruction metrics, showing strong reconstruction not to be a prerequisite for strong segmentation.

Fig. 3: Predicted tissue segmentations overlaid on intermediate reconstruction pipeline outputs, along with ground truth, for a sample test set slice. All segmentations for this slice maintained strong fidelity to ground truth. K-nirsh reconstruction output, despite poor reconstruction metrics, perceptually is very sharp and segmentation quality was the strongest, showing the features desired for strong reconstruction may not be the features desired as input for optimal segmentation performance.

Fig. 4: Plots of SSIM and PSNR against weighted DSC, on a per patient basis, for top 4 submissions across the test set (n=50). Plots again show no relation between reconstruction and segmentation metrics, but moreover, within each team Pearson’s r indicates very limited and sometimes negative correlation between reconstruction and segmentation metrics. Reconstruction and segmentation are shown to be fundamentally different tasks.

Fig. 5: Cartilage segmentations were converted into triangulated meshes, with thicknesses calculated for each patient by sampling a cartilage skeletonization. Thickness measurements were highly correlated to ground truth for 3 of the 4 teams, with another 3 of the 4 showing minimal bias and strong fidelity to ground truth. Interestingly, UglyBarnacle showed slightly better correlation in femoral and tibial cartilage despite lower DSCs, demonstrating further potential for task-specific optimization.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0859