0858

Free-Breathing Hyperpolarized Xenon-129 Spectroscopy with Cardiopulmonary Gating

Faraz Amzajerdian1, Hooman Hamedani1, Ryan Baron1, Mostafa Ismail1, Luis Loza1, Kai Ruppert1, Stephen Kadlecek1, and Rahim Rizi1

1Radiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

1Radiology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Hyperpolarized MR (Gas), Lung

While hyperpolarized 129Xe (HXe) MRI is capable of quantifying gas exchange, these measurements are heavily dependent on both cardiac and pulmonary activity. Since traditional HXe approaches are performed during extended breath-holds at fixed lung inflation levels, the measured gas exchange can differ greatly based on the chosen inflation position, and may thus not be representative of steady-state behavior. To explore the sensitivity of HXe to cardiac pulsations and the different phases of respiration, we acquired spectra continuously over approximately 40 breaths of low-dose HXe before retrospectively gating the signals based on both cardiac and respiratory cycles.Introduction

Hyperpolarized 129Xe (HXe) MRI takes advantage of xenon’s distinct chemical shifts in airspaces vs. when dissolved in alveolar tissue membrane (Mem) and red bloods cells (RBC) to quantify gas exchange. Because exchange between these three compartments reflects underlying cardiopulmonary physiology, to fully characterize HXe gas transfer it is necessary to explore the extent to which xenon is susceptible to different phases of the respiratory and cardiac cycles. While the relationship between cardiac oscillations and RBC signal has been previously explored1,2, these studies were performed using breath-holds or single-breath spectroscopy techniques, and may therefore not be representative of the steady-state dynamics during natural breathing. Here, we continuously acquired HXe spectra and blood volume measurements from a spontaneously breathing subject over several minutes, then retroactively gated the signals based on both respiratory and cardiac phases.Methods

A healthy subject was imaged in a 1.5T scanner (Magnetom Avanto, Siemens) using an 8-channel 129Xe coil (Stark Contrast, Germany); a prototype commercial system (XeBox-E10, Xemed LLC, NH) was used to polarize 87% enriched xenon-129. 50 mL of HXe was delivered with every inhalation while the subject freely breathed room air. Blood volumes were recorded via an MRI-compatible photoplethysmogram (PPG) secured to an index finger. Spectra were continuously acquired with a 28° 0.9 ms Gaussian RF pulse centered on the RBC frequency (218 ppm). ~13,300 free induction decays (FIDs) were acquired in approximately 3 min. Each FID had 2048 sample points with a dwell-time of 5 µs and TR/TE of 15/0.5 ms. The FIDs were Fourier transformed and the complex signal of each resonance was fit to a pseudo-Voigt function from which amplitudes, widths, and phases of each peak were derived. The PPG signal was bandpass filtered to isolate contributions from the heart and remove oscillations due to breathing. The gas-phase (GP) HXe signal was used as a surrogate for diaphragm position in order to retroactively bin the data into 24 distinct phases of the breathing cycle, while the filtered PPG signal was likewise used to bin the data into 24 phases of the cardiac cycle. Finally, to fully characterize the influence of cardiac pulsations and lung inflation level on xenon signal, gating was performed based on both the respiratory and cardiac cycles.Results and Discussion

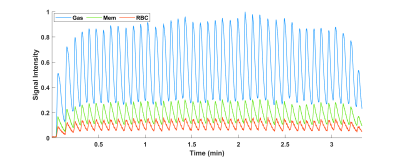

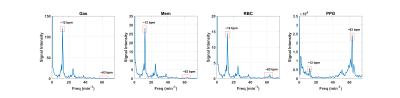

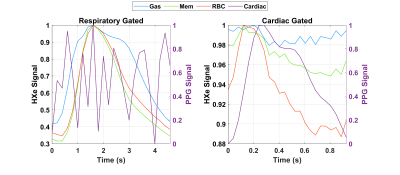

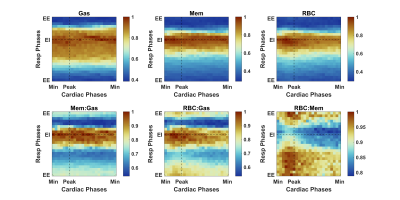

Normalized gas, membrane, and RBC amplitudes over the course of imaging are shown in Figure 1, illustrating xenon signal intensity’s dependence on breathing and highlighting the characteristic high-frequency oscillations in the RBC signal. Figure 2 shows the Fourier transforms of these signals along with the PPG curves, confirming that the ~63 beats/min oscillations in the RBC and membrane (albeit to a lesser extent in the latter) are directly due to cardiac pulsations and have negligible impact on gas signal intensity. Figure 3 shows normalized HXe and filtered PPG signals after retroactive gating based on either respiratory or cardiac phase: the approximately 120 ms offset between cardiac-gated peak RBC and PPG signals most likely reflects blood travel time from the heart to the PPG transducer on the subject’s finger. After cardiac gating, the shapes of the RBC signal and measured blood volumes closely resemble each other—although the RBC signal decreases more quickly, possibly due to transport or exchange processes, or to rapid depolarization from repeated RF excitations. The membrane signal initially mirrors the RBC signal but does not decay completely, potentially reflecting the volume of xenon that did not exchange with the RBCs. The gas signal experiences an approximately 2% drop at the peak of the cardiac pulsation but otherwise remains constant, possibly representing a redistribution of the gas due to motion of the heart or increased diffusion into the alveolar membrane and/or RBCs.Figure 4 shows HXe signals after simultaneously gating on both respiratory and cardiac phases, illustrating the varying cardiopulmonary-dependent trends in gas exchange between HXe compartments. As expected, global gas, membrane, and RBC signals increase during inhalation, peaking at end-inhale (EI), when the concentration of HXe is highest, and decreasing during exhale. The ratios of these signals and the exchange between the compartments, however, differ greatly across the respiratory and cardiac cycles. For the Mem:Gas and RBC:Gas, the ratios at end-exhale (EE) are elevated due to lingering dissolved HXe after exhalation, decrease briefly during inhale as gas signal increases more rapidly than diffusion into the alveolar tissue, and then increase to their maximum value at EI. During exhale, the initial drop in the ratios results from dissolved xenon being more quickly transported downstream than the gas being exhaled. Exchange between RBCs and membrane, on the other hand, is lowest at EI but increases throughout exhalation. Differences in the signal dynamics across the cardiac phases at different respiratory phases are also apparent, particularly for RBC:Gas and RBC:Mem.

Conclusion

Dynamic xenon spectroscopy, in conjunction with blood volume measurements, provides additional insight into observed gas exchange’s dependence on cardiopulmonary physiology.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Niedbalski P, et al. Mapping cardiopulmonary dynamics within the microvasculature of the lungs using dissolved 129Xe MRI. J Appl Physiol. 2020;129:218-229

2. Bier E, et al. A protocol for quantifying cardiogenic oscillations in dynamic 129Xe gas exchange spectroscopy: The effects of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. NMR Biomed. 2019;32:e4029

Figures

Figure 1. Gas, membrane,

and RBC peak amplitudes (normalized to max gas signal) from continuously

acquired spectra in a spontaneously breathing healthy subject. The gas signal,

specifically, mirrors breathing, and was used as a surrogate for diaphragm

position when retrospectively gating based on respiratory cycle.

Figure 2. Fourier

transforms of each xenon resonance as well as blood volume measurements

(recorded from a PPG transducer on the subject’s finger). Peaks at 12 bpm (and

corresponding harmonics) indicate the breathing rate, while the peak at 63 bpm

reflects the heart rate. The cardiac oscillations are apparent with the RBC and,

to a lesser extent, the membrane.

Figure 3. Normalized HXe (left axis) and filtered PPG signals (right axis), retrospectively gated into 24 respiratory or cardiac

phases. The respiratory gating reveals the rapid increase during inhalation and

slow decrease during exhalation of gas-phase compared to dissolved-phase xenon,

while the cardiac gating illustrates the strong correlation of between blood

volumes and HXe RBC signal.

Figure 4. Normalized HXe

resonances and ratios simultaneously gated into both respiratory and cardiac

phases, revealing changing dynamics during inhalation and exhalation (top to

bottom) and across a cardiac pulsation (left to right).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0858