0822

Architecture-agnostic Deep Image Prior for Accelerated MRI reconstruction1Department of Computer Science, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States, 2Department of Radiology, Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH, United States, 3Department of Radiology, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Image Reconstruction, Machine Learning/Artificial Intelligence

This work aims to simplify deep image prior (DIP) architectural design decisions in the context of unsupervised accelerated MRI reconstruction, facilitating the deployment of MRI-DIP in real-world settings. We first show that architectures inappropriate for specific MRI datasets (knee, brain) can lead to severe reconstruction artifacts, and then demonstrate that proper network regularization can dramatically improve image quality irrespective of network architectures. The proposed plug-and-play regularization is applicable to any network form without architectural modifications.Introduction

Deep image prior (DIP) [1] inspired networks, which can be trained on a per image basis without ground truth, have been recently applied for unsupervised MRI reconstruction. The success of DIP has been widely attributed to the spectral bias inherent in the network architectures [2-4]. Our investigation indicates that changes in basic network properties such as width and depth critically influence the reconstruction outcome. However, choosing an architecture that is tailored for a particular dataset from a plethora of candidates is non-trivial. As a remedy, we propose to manipulate the extents of spectral bias of the network via Lipschitz regularization. The convolutional layers and the activation functions are Lipschitz-controlled and the per-layer Lipschitz constants are learnt during the training. Results obtained from the 4x and 6x accelerated brain and knee datasets [6] demonstrate that our method greatly improves the reconstruction results in spite of the ill-designed network architectures, effectively reducing the influences of poor architectural choices in DIP-based MRI reconstruction.Methods

The frequency spectrum that can be encoded by a neural network is controllable by enforcing Lipschitz continuity [5]. Different Lipschitz constants thus result in different extents of spectral bias. To this end, we upper-bound the spectral norm of the convolutional layers to particular Lipschitz constants that are learned end-to-end in training. To allow for Lipschitz-controlled nonlinearities, we replace the commonly-used ReLU activation functions with learnable piecewise-linear spline activation functions. To favor the learning of lower frequencies, we encourage smaller Lipschitz constants by augmenting the typical reconstruction loss with a regularization term, defined as the product of per-layer Lipschitz constants, giving the total loss:$$ J(Θ,C)=L(y;AG_θ (z))+λ\prod_{i=1}^l softplus(c_i)$$, where $$$C = \{c_i\}$$$ is the set of per-layer Lipschitz constants that are learned jointly with the network weights $$$\Theta$$$. The softplus function prevents infeasible negative Lipschitz bounds. y denotes the under-sampled measurements, and A denotes the measurement model, which includes an under-sampling mask, Fourier Transform, and coil sensitivity maps (optional). $$$G_{\theta}(z)$$$ is the parameterization of the reconstructed image via a convolutional neural network that takes a fixed random noise vector as input, following the DIP framework. An overview of our method is shown in Fig 1.

Experiments were conducted based on the publicly available multi-coil fastMRI knee and brain datasets [6], which respectively contain 1594 and 6970 fully sampled scans, acquired on various 1.5T and 3T Siemens MRI scanners. The data was acquired using a conventional cartesian 2D TSE protocol with a phase-array coil and a matrix size of 320 x 320. The ground truth was obtained by computing the root-sum-of-squares (RSS) reconstruction method applied to fully sampled k-space data. For both datasets, the k-space data used to test the networks was obtained by applying a mask on the fully sampled data (7% of central k-space lines along with an uniform undersampling at outer k-space, yielding in effect 4x or 6x acceleration).

Results

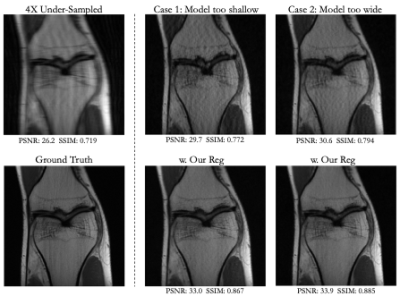

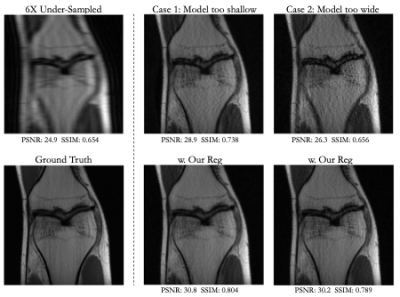

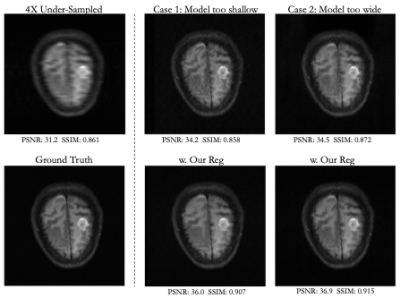

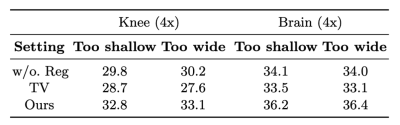

Visual and numerical results for the multi-coil knee and brain datasets under 4x and 6x acceleration are shown in Figs. 2-5 and Tab. 1. We tested U-Net architectures with typical widths (128 vs. 256 channels) and depths (3 levels vs. 5 levels). Additional results for total-variation (TV) regularized DIP [7] are shown in Tab 1. Figs. 2-5 indicate that suboptimal architectures lead to severe artifacts in the reconstructed images (top rows). Utilizing our regularization strategy, we observe appreciable improvements in image quality over the baselines, especially for 4x acceleration. Notably, the extent of improvement is similar regardless of the architecture. This suggests that controlling the frequency biases of the network architecture via proper regularization might be as effective as modifying the architecture in DIP based reconstruction. In contrast, TV regularization does not exhibit comparable performance. Our strategy works consistently on MR images acquired from different organs (i.e., knee and brain).Discussion

Our results have two important implications: 1) DIP based reconstruction is sensitive to architectural choices, and 2) it is possible to explicitly manipulate the frequency biases without the need for architectural modifications. The latter is a major advantage for DIP to be deployed in practice, as how to optimize the network architecture for particular datasets remains an open problem, which often leads to an excessively large design space that could be both time and computationally-expensive. With the promising results presented above, our work suggests an efficient alternative that obviates the need for exhaustive architectural search.Conclusion

This work investigated the influences of architectural choices on unsupervised MRI reconstruction with the deep image prior framework, and proposed a novel regularization strategy to substantially improve the reconstruction without tedious architectural design. Future work will be focused on extensive hyper-parameter tuning for more effective network regularization to improve performance under more aggressive acceleration factors.Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the United States National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Grant R01EB006733 and Grant R01CA266702.References

[1] Ulyanov, Dmitry, Andrea Vedaldi, and Victor Lempitsky. "Deep image prior." Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition. 2018.

[2] Chakrabarty, Prithvijit, and Subhransu Maji. "The spectral bias of the deep image prior." arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.08905(2019).

[3] Heckel, Reinhard, and Mahdi Soltanolkotabi. "Denoising and regularization via exploiting the structural bias of convolutional generators." arXiv preprint arXiv:1910.14634 (2019).

[4] Chen, Yun-Chun, et al. "Nas-dip: Learning deep image prior with neural architecture search." European Conference on Computer Vision. Springer, Cham, 2020.

[5] Katznelson, Yitzhak. An introduction to harmonic analysis. Cambridge University Press, 2004.International Journal of Computer Vision 130.4 (2022): 885-908.

[6] Zbontar, Jure, et al. "fastMRI: An open dataset and benchmarks for accelerated MRI." arXiv preprint arXiv:1811.08839 (2018).

[7] Liu, Jiaming, et al. "Image restoration using total variation regularized deep image prior." ICASSP 2019-2019 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP). Ieee, 2019.

Figures