0818

Automated Processing and Segmentation of Abdominal Structures Using a Hybrid Attention-Convolutional Neural Network Model

Nicolas Basty1, Ramprakash Srinivasan2, Marjola Thanaj1, Elena P Sorokin2, Madeleine Cule2, E Louise Thomas1, Jimmy D Bell1, and Brandon Whitcher1

1University of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, 2Calico Life Sciences LLC, South San Francisco, CA, United States

1University of Westminster, London, United Kingdom, 2Calico Life Sciences LLC, South San Francisco, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Data Analysis, Body, Deep learning, Dixon

Automated image processing and organ segmentation are critical to the quantitative analysis of population-scale imaging studies. We have implemented an end-to-end pipeline for neck-to-knee Dixon MRI data based on the UK Biobank abdominal protocol. Bias-field correction, blending across series boundaries, and fat-water swap correction are performed in the preprocessing steps. A hybrid attention-convolutional neural network model segments multiple abdominal organs, major bones, along with adipose and muscle tissue. The application of neural network models, to both swap detection and segmentation, produces a computationally-efficient pipeline that scales to accommodate tens of thousands of datasets.Introduction

Over the last 20 years, MRI has become the gold standard for body composition, with many of these measurements having an enormous impact on our understanding of metabolic conditions 1. Body composition studies based on large medical imaging databases such as the UK Biobank (UKBB), require automated and robust preprocessing and quality control to produce accurate image biomarkers for downstream analyses. We present an automated end-to-end preprocessing and segmentation pipeline for the UKBB abdominal MRI protocol.Methods

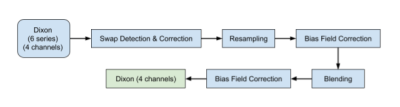

The data included here focused on the neck-to-knee Dixon MRI acquisition from the UKBB MR abdominal protocol 2. The six separate series were resampled to a single dimension and resolution to facilitate merging them into a single three-dimensional volume. Four sets of DICOM files were generated for each of the six series in the neck-to-knee Dixon protocol: in-phase, opposed-phase, fat, and water. The preprocessing steps are summarised in Fig. 1.To identify fat-water swaps of the entire series, we used a convolutional neural network (CNN) model on a series-by-series basis, with six individual models trained for each of the six acquired series. Using the central 2D coronal image as input, each convolution block was made up of N convolutions that were 3⨉3 spatial filters applied with stride length two, followed by a ReLU activation function and batch normalisation. The final layer had stride length three and a sigmoid activation for binary classification of the input as either water or fat. The number of convolution filters was doubled in each layer down the network as follows: C64 → C128 → C256 → C512 → C1024 → C1. The model was trained with a binary cross entropy loss function using the Adam optimizer and a batch size of 100 until convergence, between 150 and 200 epochs. The models were trained on 462 participants without swaps and validated on a separate set of 615 participants.

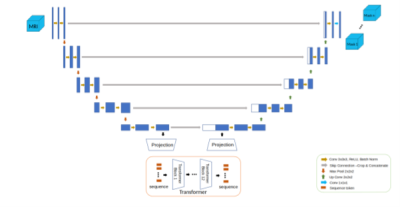

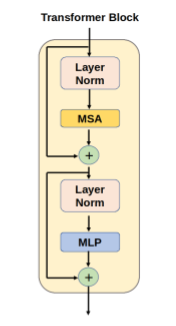

The segmentation model (Figs. 2 and 3) was designed as a UNet-like encoder-decoder, with a transformer encoder that operates on the coarsest resolution output of the UNet encoder. The architecture was inspired by the TransUNet 3, a hybrid CNN-Transformer that leverages both the high spatial fidelity of CNNs, and the ability of transformers to model global context. The CNN encoder is a canonical sequence of convolutional layers that iteratively downsamples the spatial resolution by approximately half, while the number of convolutional filters is doubled. The encoder used four such convolutional blocks, consisting of a sequence of C1x1 → C3x3 → C1x1 operators, with the final convolution using double the filters compared with the previous block. The output of the encoder was a volume of dimension [1024, H/16, W/16, D/16], where H, W, and D are the original height, width, and depth dimensions of the input volume, respectively. The activation map from the convolutional encoder was propagated through a sequence of transformer blocks. Each transformer block consisted of a multi-headed self-attention layer 4. The encoded volume was decoded using a UNet-style convolutional decoder with transposed convolutional blocks that mirror the convolutional encoder. The decoder blocks were spatially upsampled by a factor of two while reducing the number of activation maps by a factor of two. The output was resized using trilinear interpolation to match the input acquisition. Every CNN encoder block, decoder block, and multilayer perceptron layer included a normalisation layer and a non-linearity.

Results

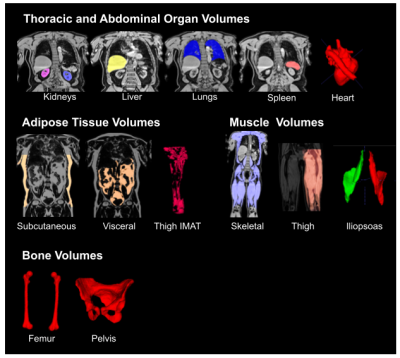

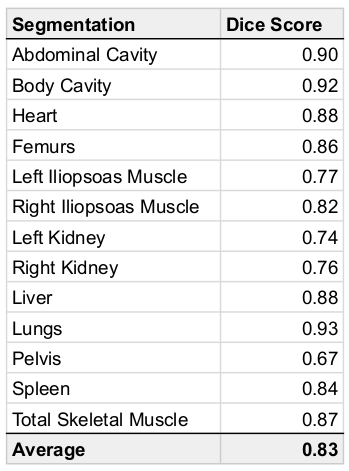

We used 38,695 datasets from the UKBB; since fat-water swaps may occur in each of the six series independently, we checked a total of 38,695 ⨉ 8 = 390,560 acquisitions for swaps. Of these, 787 (0.16%) had a fat-water swap, occurring in 690 (1.8%) subjects. The second series, covering the chest, contained the most swaps (348) followed by the fifth series (233), covering the upper thighs. In the first series we found 52 swaps, the third series 61 swaps, the fourth series 9 swaps, and the sixth series 84 swaps.The segmentation network detected 28 different organs and tissues (classes) in the abdominal protocol, from 294 annotated Dixon acquisitions. Each acquisition was manually annotated with the ground truth voxels for a variable number of classes. Annotated datasets were divided into training and validation subsets, where the number of annotated samples per class approximately followed an 80-20% split. Segmentation performance was measured using the validation Dice similarity coefficient for each class. Table 1 provides the performance metrics for our method, which produced an average Dice score of 0.83 across classes without post-processing and 0.87 with post-processing.

Discussion and Conclusion

Here, we described an image analysis pipeline for Dixon acquisitions from the UK Biobank abdominal MRI protocol that includes multiple automated steps. Swap detection was optimised and applied to the six series in the Dixon acquisitions. The segmentation model produced anatomically accurate output for a wide variety of abdominal organs, muscle tissue, fat tissue, and bones (Fig. 3). Going forward we will apply the pipeline to the remaining subjects from the UKBB imaging cohort (100,000 subjects in total) and the repeat scans.Acknowledgements

This research has been conducted using the UK Biobank Resource under Application Number 44584 and was funded by Calico Life Sciences LLC.References

- Thomas, EL, Fitzpatrick, JA, Malik, SJ, et al. Whole body fat: Content and distribution. Prog in Nucl Mag Res Spec 2013; 73: 56-80.

- Littlejohns TJ, Holliday J, Gibson LM, et al. The UK Biobank imaging enhancement of 100,000 participants: rationale, data collection, management and future directions. Nat Commun 2020; 11(1): 1-12.

- Chen, J, Lu, Y, Luo, X, et al. TransUNet: Transformers make strong encoders for medical image segmentation. arXiv preprint 2021; 2102.04306.

- Bahdanau, D, Cho, K, Bengio, Y. Neural machine translation by jointly learning to align and translate. arXiv preprint 2014; 1409.0473.

Figures

Figure 1: Workflow for the Dixon acquisition protocol, where the data include a total of 24 DICOM series (four channels and six series) that go through several steps to produce high-quality neck-to-knee image volumes.

Figure 2: Architecture for the hybrid attention-convolutional neural network model.

Figure 3: Architecture for the transformer block in the hybrid attention-convolutional neural network model. MSA: multi-headed self-attention, MLP: multi-layer perceptron.

Figure 4: Segmented organs and tissue from the neck-to-knee Dixon acquisition using the hybrid attention-convolutional neural network model. IMAT: intermuscular adipose tissue.

Table 1: Dice scores for organs, tissue and bone using the hybrid attention-convolutional neural network model.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0818