0804

Comparing 3D, 2.5D, and 2D Approaches to Brain MRI Segmentation1Therapeutic Radiology, Yale Unviersity, New Haven, CT, United States, 2Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States, 3Division of Cardiovascular Medicine, Yale Unviersity, New Haven, CT, United States, 4Therapeutic Radiology, Yale University, New Haven, CT, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Segmentation, Segmentation

We compared 3D, 2.5D, and 2D approaches to brain MRI auto-segmentation and concluded that the 3D approach is more accurate, achieves better performance when training data is limited, and is faster to train and deploy. Our results hold across various deep-learning architectures, including capsule networks, UNets, and nnUNets. The only downside of 3D approach is that it requires 20 times more computational memory compared to 2.5D or 2D approaches. Because 3D capsule networks only need twice the computational memory that 2.5D or 2D UNets and nnUNets need, we suggest using 3D capsule networks in settings where computational memory is limited.Introduction

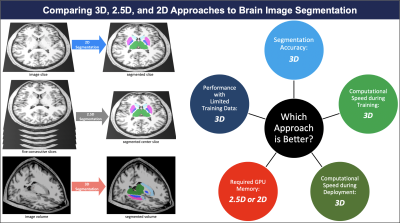

Segmentation of brain magnetic resonance images (MRIs) has widespread applications in the management of neurological disorders, radiotherapy planning, and neurosurgical navigation.1–3 Manual segmentation is time-consuming and is prone to intra- and inter-observer variability.4 As a result, deep learning auto-segmentation methods are increasingly being used.5There are three proposed approaches to auto-segmentation of 3D brain MRIs (Figure 1): 1) analyze and segment a two-dimensional slice of the image at a time (2D),6 2) analyze five consecutive two-dimensional slices at a time to generate a segmentation of the middle slice (2.5D),7 and 3) analyze and segment the image volume in the three-dimensional space (3D).6 Although each approach has shown some promise in medical image segmentation, a comprehensive comparison and benchmarking of these approaches for auto-segmentation of brain MRIs is lacking. Prior studies have not evaluated their efficacy in segmenting brain MRIs, limited their comparison narrowly to one deep learning architecture, 6,8–10 and focused primarily on segmentation accuracy and ignored metrics such as computational efficiency or accuracy in data-limited settings.

In this study, we comprehensively compared 3D, 2.5D, and 2D approaches to brain MRI auto-segmentation across three different deep learning architectures and used metrics of accuracy and computational efficiency.

Methods

We used 3,430 T1-weighted brain MRIs from Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) study to train and test our models.11 The MRIs were randomly split into training (3,199 MRIs), validation (117 MRIs), and test (114 MRIs) sets at the patient level. MRI preprocessing included B1-field and intensity inhomogeneity correction, skull stripping, and patching.12,13 Preliminary ground-truth segmentations were generated by FreeSurfer,14–16 and were manually corrected by a board-eligible radiologist (AA).We compared the 3D, 2.5D, and 2D approaches across three auto-segmentation models: capsule networks (CapsNets),17 UNets,18 and nnUNets.19 These models are the highest-performing auto-segmentation models in the biomedical domain.5,17,19–24 We trained the CapsNet and UNet models for 50 epochs using Dice loss and the Adam optimizer.25 Initial learning rate was 0.002. We used dynamic paradigms for learning rate scheduling, with minimal learning rate of 0.0001. The hyperparameters for the nnUNet model were self-configured by the model.19

We compared 3D, 2.5D, and 2D approaches using the following metrics: 1) Segmentation accuracy, quantified by Dice score;26 2) Performance when training data is limited; 3) Computational speed during training and deployment; and 4) required GPU memory. The code used to train and test our models is available at: https://github.com/Aneja-Lab-Yale/Aneja-Lab-Public-3D2D-Segmentation.

Results

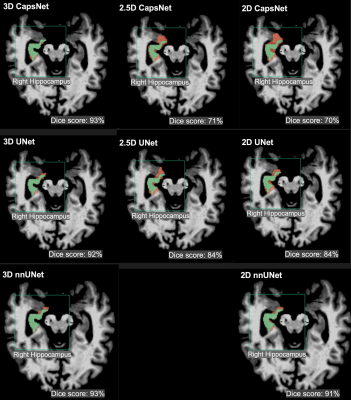

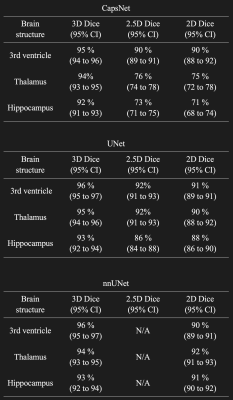

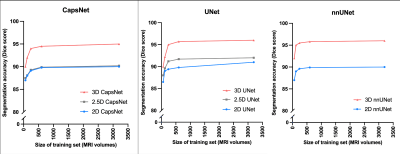

The segmentation accuracy of the 3D approach across all models and all anatomic structures of the brain was higher than 2.5D or 2D approaches, with Dice scores of the 3D models above 90% for all anatomic structures (Figure 2 and Table 1). 3D models maintained higher accuracy, compared to 2.5D and 2D models, when training data was limited (Figure 3). 3D models converged 20% to 40% faster compared to 2.5D or 2D models (Figure 4). Fully-trained 3D models segment could a brain MRI 30% to 50% faster compared to fully-trained 2.5D or 2D models (Figure 4). 3D models required 20 times more GPU memory compared to 2.5D or 2D models (Figure 4).Discussion

Our study extends the prior literature 6,8,9,27,28 in key ways. We provide the first comprehensive benchmarking of 3D, 2.5D, and 2D approaches in auto-segmenting brain MRIs across different auto-segmentation architectures, measuring both accuracy and computational efficiency. We found that the 3D approach gives higher segmentation accuracy across different auto-segmentation architectures, maintains higher accuracy in the context of limited training data, and trains and deploys faster compared to 2.5D or 2D approaches. Previous studies have concluded conflicting results, particularly about computational speed. 6,9,28 Notably, one training iteration of 2.5D or 2D models is faster than 3D models because 2.5D and 2D models have 20 times fewer parameters. However, 2.5D and 2D models require a for loop that iterates through image slices, slowing down training. Additionally, 3D models converge faster because they use contextual information in the 3D image volume.6 Conversely, 2.5D and 2D models can only use the contextual information in a few slices of the image, making them slower to converge.7 Lastly, each training iteration through 3D models can be accelerated by larger GPU memory, since training can be parallelized. However, each training iteration through 2.5D or 2D models cannot be accelerated by larger GPUs because iterations through image slices (for loop) cannot be parallelized. Our results also highlighted the main drawback of 3D approach: it requires 20 times more GPU memory compared to 2.5D or 2D approaches.Conclusions

In this study, we compared 3D, 2.5D, and 2D approaches to brain image auto-segmentation across different deep-learning models and concluded that the 3D approach is more accurate, achieves better performance in the context of limited training data, and is faster to train and deploy. Our results hold across various auto-segmentation models, including capsule networks, UNets, and nnUNets. The only downside of the 3D approach is that it requires 20 times more computational memory compared to the 2.5D or 2D approaches. Because 3D capsule networks only need twice the computational memory that 2.5D or 2D UNets and nnUNets need, we suggest using 3D capsule networks in settings where computational memory is limited.Acknowledgements

Arman Avesta is a PhD Student in the Investigative Medicine Program at Yale which is supported by CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR001863 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science, a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). This work was also supported by the Radiological Society of North America’s (RSNA) Fellow Research Grant Number RF2212. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of NIH or RSNA.

References

1. Feng CH, Cornell M, Moore KL, et al. Automated contouring and planning pipeline for hippocampal-avoidant whole-brain radiotherapy. Radiat Oncol Lond Engl 2020;15:251.

2. Dasenbrock HH, See AP, Smalley RJ, et al. Frameless Stereotactic Navigation during Insular Glioma Resection using Fusion of Three-Dimensional Rotational Angiography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. World Neurosurg 2019;126:322–30.

3. Dolati P, Gokoglu A, Eichberg D, et al. Multimodal navigated skull base tumor resection using image-based vascular and cranial nerve segmentation: A prospective pilot study. Surg Neurol Int 2015;6:172.

4. Lorenzen EL, Kallehauge JF, Byskov CS, et al. A national study on the inter-observer variability in the delineation of organs at risk in the brain. Acta Oncol 2021;60:1548–54.

5. Duong MT, Rudie JD, Wang J, et al. Convolutional Neural Network for Automated FLAIR Lesion Segmentation on Clinical Brain MR Imaging. Am J Neuroradiol https://doi.org/10.3174/ajnr.A6138.

6. Zettler N, Mastmeyer A. Comparison of 2D vs. 3D U-Net Organ Segmentation in abdominal 3D CT images. 2021 Jul 8. [Epub ahead of print].

7. Ou Y, Yuan Y, Huang X, et al. LambdaUNet: 2.5D Stroke Lesion Segmentation of Diffusion-weighted MR Images. https://doi.org/10.48550/arXiv.2104.13917.

8. Bhattacharjee R, Douglas L, Drukker K, et al. Comparison of 2D and 3D U-Net breast lesion segmentations on DCE-MRI. In: Medical Imaging 2021: Computer-Aided Diagnosis.Vol 11597. SPIE; 2021:81–7.

9. Kern D, Klauck U, Ropinski T, et al. 2D vs. 3D U-Net abdominal organ segmentation in CT data using organ bounds. In: Medical Imaging 2021: Imaging Informatics for Healthcare, Research, and Applications.Vol 11601. SPIE; 2021:192–200.

10. Kulkarni A, Carrion-Martinez I, Dhindsa K, et al. Pancreas adenocarcinoma CT texture analysis: comparison of 3D and 2D tumor segmentation techniques. Abdom Radiol N Y 2021;46:1027–33.

11. Crawford KL, Neu SC, Toga AW. The Image and Data Archive at the Laboratory of Neuro Imaging. NeuroImage 2016;124:1080–3.

12. Fischl B, Salat DH, Busa E, et al. Whole brain segmentation: automated labeling of neuroanatomical structures in the human brain. Neuron 2002;33:341–55.

13. Ganzetti M, Wenderoth N, Mantini D. Quantitative Evaluation of Intensity Inhomogeneity Correction Methods for Structural MR Brain Images. Neuroinformatics 2016;14:5–21.

14. Clerx L, Gronenschild EHBM, Echavarri C, et al. Can FreeSurfer Compete with Manual Volumetric Measurements in Alzheimer’s Disease? Curr Alzheimer Res 2015;12:358–67.

15. Ochs AL, Ross DE, Zannoni MD, et al. Comparison of Automated Brain Volume Measures obtained with NeuroQuant and FreeSurfer. J Neuroimaging Off J Am Soc Neuroimaging 2015;25:721–7.

16. Fischl B. FreeSurfer. NeuroImage 2012;62:774–81.

17. Avesta A, Hui Y, Krumholz HM, et al. 3D Capsule Networks for Brain MRI Segmentation. medRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/2022.01.18.22269482.

18. Yin X-X, Sun L, Fu Y, et al. U-Net-Based Medical Image Segmentation. J Healthc Eng 2022;2022:4189781.

19. Isensee F, Jaeger PF, Kohl SAA, et al. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nat Methods 2021;18:203–11.

20. Rudie JD, Weiss DA, Colby JB, et al. Three-dimensional U-Net Convolutional Neural Network for Detection and Segmentation of Intracranial Metastases. Radiol Artif Intell 2021;3:e200204.

21. LaLonde R, Xu Z, Irmakci I, et al. Capsules for biomedical image segmentation. Med Image Anal 2021;68:101889.

22. Rauschecker AM, Gleason TJ, Nedelec P, et al. Interinstitutional Portability of a Deep Learning Brain MRI Lesion Segmentation Algorithm. Radiol Artif Intell 2022;4:e200152.

23. Rudie JD, Weiss DA, Saluja R, et al. Multi-Disease Segmentation of Gliomas and White Matter Hyperintensities in the BraTS Data Using a 3D Convolutional Neural Network. Front Comput Neurosci 2019;13.

24. Weiss DA, Saluja R, Xie L, et al. Automated multiclass tissue segmentation of clinical brain MRIs with lesions. NeuroImage Clin 2021;31:102769.

25. Yaqub M, Jinchao F, Zia MS, et al. State-of-the-Art CNN Optimizer for Brain Tumor Segmentation in Magnetic Resonance Images. Brain Sci 2020;10:E427.

26. Taha AA, Hanbury A. Metrics for evaluating 3D medical image segmentation: analysis, selection, and tool. BMC Med Imaging 2015;15:29.

27. Sun Y-C, Hsieh A-T, Fang S-T, et al. Can 3D artificial intelligence models outshine 2D ones in the detection of intracranial metastatic tumors on magnetic resonance images? J Chin Med Assoc JCMA 2021;84:956–62.

28. Nemoto T, Futakami N, Yagi M, et al. Efficacy evaluation of 2D, 3D U-Net semantic segmentation and atlas-based segmentation of normal lungs excluding the trachea and main bronchi. J Radiat Res (Tokyo) 2020;61:257–64.

Figures

Figure 2: Examples of 3D, 2.5D, and 2D segmentations of the right hippocampus by CapsNet, UNet, and nnUNet. Target segmentations and model predictions are respectively shown in green and red. Dice scores are provided for the entire volume of the right hippocampus in this patient (who was randomly chosen from the test set).

Table 1: Comparing the segmentation accuracy of 3D, 2.5D, and 2D approaches across three auto-segmentation models to segment brain structures. The three auto-segmentation models included CapsNet, UNet, and nnUNet. These models were used to segment three representative brain structures: 3rd ventricle, thalamus, and hippocampus, which respectively represent easy, medium, and difficult structures to segment. The segmentation accuracy was quantified by Dice scores over the test (114 brain MRIs).

Figure 3: Comparing 3D, 2.5D, and 2D approaches when training data is limited. We trained the models using the complete training with 3199 MRIs, as well as random subsets of the training set with 600, 240, 120, and 60 MRIs. The models trained on these subsets were then evaluated over the test set. The 3D models maintained higher segmentation accuracy (measured by Dice scores) across all experiments.

Figure 4: Comparing the computational efficiency of 3D, 2.5D, and 2D approaches. The top panel compares training times needed (per training example per epoch) for each model to converge, and the deployment times needed by each fully-trained model to segment one brain MRI. The 3D approach trained and deployed faster across all experiments. The bottom panel compares the required GPU memory between the three approaches. Within each auto-segmentation model (CapsNet, UNet, and nnUNet), the 3D approach requires 20 times more computational memory compared to 2.5D or 2D approaches.