0792

Application of 3D Cones Trajectory Acquisition in Hepatobiliary MR Imaging for Detection of Hepatic Lesions1Radiology Body MRI, Stanford Medicine, Palo Alto, CA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Liver, Liver, Free-breathing MRI, hepatobiliary imaging, 3D cones with golden-angle ordering

Conventional cartesian T1 weighted 3D spoiled gradient recalled echo imaging with respiratory navigation (3D-SPGR-NAV) can help mitigate motion artifacts in post contrast liver imaging but suffer from respiratory rate dependence. 3D cones trajectories with golden angle ordering (T1g) allow continuous sampling during free-breathing liver imaging. We compared the diagnostic performance of an accelerated T1g (T1gER) versus 3D-SPGR-NAV in liver lesion detection. Two readers reviewed imaging from 35 patients containing 127 hepatic lesions. T1gER was non-inferior to 3D-SPGR-NAV for <5 mm and >=10 mm lesions. 3D-SPGR-NAV was superior for lesions 5-9 mm, possibly due to susceptibility artifact on the T1gER images.Category

Primary Category: BodyPrimary Category Keyword: Liver

General Keyword: Liver

other general keywords: Free-breathing MRI, hepatobiliary imaging, 3D cones with golden-angle ordering

Secondary Category: --- none ---

Secondary Label: --- none ---

Presentation Style: Oral Preferred

Summary of Main Findings

This study shows free-breathing hepatobiliary imaging using a 3D cones trajectory with golden angle ordering and extended readout has similar diagnostic performance compared to conventional cartesian 3D spoiled gradient recalled echo with respiratory navigation for detecting liver lesions, but with a shorter and predictable image acquisition time, independent of respiratory rate.Introduction

Hepatobiliary phase (HBP) MRI with Gadoxetate offers optimal accuracy in liver lesion detection over other imaging modalities.[1, 2] Conventional post-contrast liver MRI uses a 3-dimensional fat-suppressed T1 weighted spoiled gradient echo sequence with a cartesian readout (3D-SPGR) and a breath hold (BH) for respiratory motion mitigation. However, many patients with advanced liver disease have breath-holding difficulties. In this setting, gated free-breathing imagining, for example using navigator pulses (NAV), can be effective but unpredictably increase scan time due to respiratory rate dependence and pauses in sampling. Non-cartesian k-space trajectories allow continuous sampling during free-breathing liver imaging by rendering motion artifacts incoherent, potentially saving time over navigated approaches. [3] Prior work introduced and tested a 3D cones trajectory with golden angle ordering (T1g) which allowed high quality imaging of hepatic landmarks.[4-6] We have previously shown similar image quality, motion artifact, and anatomic delineation between HBP images acquired using a navigated 3D-SPGR (3D-SPGR NAV) versus T1g with an extended readout (T1gER) to shorten scan (ISMRM 2019, abstract #1637). In this study, we aim to compare the diagnostic performance of T1gER with 3D-SPGR NAV in liver lesion detection.Methods

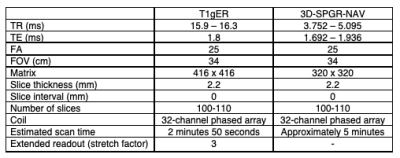

This retrospective study enrolled consecutive patients undergoing liver HBP MRI. Scans were obtained on one of six 3T scanners (GE MR 750, Waukesha, WI) using a 32-channel phased-array coil. Patients with suspected hepatic metastases who underwent HBP MRI including, at minimum, axial T2 SSFSE, axial DWI (b>=500), 3D-SPGR pre and dynamic post-contrast imaging, HBP 3D-SPGR, and HBP T1gER were included. Patients with >=12 liver lesions or those with incomplete imaging datasets were excluded. The reference standard was determined by two radiologists, one faculty with 4 years of experience and one fellow, with access to the patient record and all images. Anonymized, randomized and scrollable HBP image stacks were provided to two abdominal fellowship-trained faculty radiologists with 3 and 4 years of experience. The readers annotated each mass identified, which was compared to the reference standard. The data were analyzed on a per lesion basis[BR1] for: all lesions, lesions <5mm, lesions 5-9mm, and lesions 10mm or larger. Performance metrics including sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, and accuracy.Results

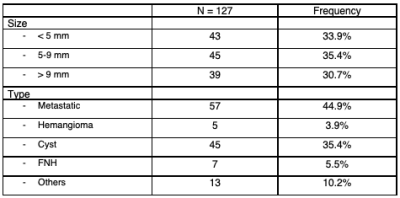

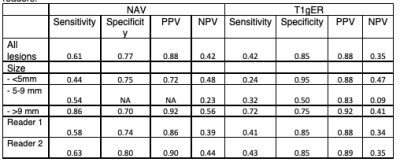

Thirty-five patients with 127 refence lesions (Table 2) were included (mean age 58.7; 49% female). Patients had on average 6.9 lesions (ranging; 0-11). Performance metrics are listed in Table 3. We found NAV acquisition has sensitivity of 0.61, whereas T1gER acquisition has 0.41. In subgroup of lesions measured larger than 9 mm, NAV had 0.87 sensitivity compared to 0.71 for T1gER. Readers had overall similar performance metrics across both sets of studies. The sensitivity of NAV by reader 1 is 0.59, whereas NAV by reader 2 has 0.63 sensitivity. Both readers had detected lesions with high specificity in T1gER studies. Both modalities were specific in all detected lesions.Discussion

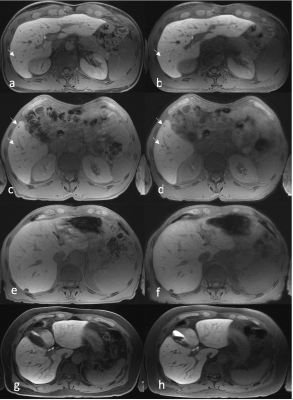

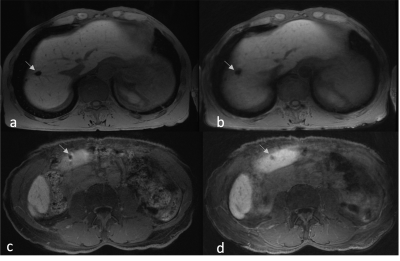

We showed that T1gER is non-inferior to conventional 3D-SPGR NAV in detecting liver lesions (Table 3 and Figure 1). In subgroup analysis, T1gER is also non-inferior for lesions less than 5 mm and at least 10mm, whereas 3D-SPGR NAV was superior to T1gER in lesions measured 5-9 mm. This may be related to the high rate of susceptibility artifacts in this group (Figure 2), which may be harder to identify in the T1gER exams due to aliasing distributed across the image inversion which yields a subtle gray background signal. The results of this study are consistent with previous data confirming the acceptable accuracy of T1gER acquisition in liver imaging.[7] Limitations include only 2 readers, a small number of patients with a moderate number of lesions, and as cases were read in 1-2 large batches reader fatigue may have impacted sensitivity, in particular for smaller lesions.Conclusion

In summary, T1gER offers a predictable and shortened image acquisition time compared to conventional 3D-SPGR NAV (<3 minutes versus an average of 5 minutes) with similar diagnostic performance and may serve as a valuable screening tool for liver lesions in patients with breathing difficulties.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Floriani, I., et al., Performance of imaging modalities in diagnosis of liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Magn Reson Imaging, 2010. 31(1): p. 19-31.

2. Grazioli, L., et al., Hepatocellular adenoma and focal nodular hyperplasia: value of gadoxetic acid-enhanced MR imaging in differential diagnosis. Radiology, 2012. 262(2): p. 520-9.

3. Azevedo, R.M., et al., Free-breathing 3D T1-weighted gradient-echo sequence with radial data sampling in abdominal MRI: preliminary observations. AJR Am J Roentgenol, 2011. 197(3): p. 650-7.

4. Chandarana, H., et al., Free-breathing radial 3D fat-suppressed T1-weighted gradient echo sequence: a viable alternative for contrast-enhanced liver imaging in patients unable to suspend respiration. Invest Radiol, 2011. 46(10): p. 648-53.

5. Zhang, T., et al., Clinical performance of a free-breathing spatiotemporally accelerated 3-D time-resolved contrast-enhanced pediatric abdominal MR angiography. Pediatr Radiol, 2015. 45(11): p. 1635-43.

6. Gurney, P.T., B.A. Hargreaves, and D.G. Nishimura, Design and analysis of a practical 3D cones trajectory. Magn Reson Med, 2006. 55(3): p. 575-82.

7. Hedderich, D.M., et al., Clinical Evaluation of Free-Breathing Contrast-Enhanced T1w MRI of the Liver using Pseudo Golden Angle Radial k-Space Sampling. Rofo, 2018. 190(7): p. 601-609.

Figures

Table 1: MRI features in T1gER and LAVA-NAV techniques.

TR: Repetition time; TE: time to echo; FOV: field of view.

Table 3: Diagnostic accuracy NAV and T1gER acquisitions divided by size of lesion and readers.

*Comparing diagnostic parameters in NAV and T1gER techniques. PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; NAV, respiratory navigated free breathing (NAV); T1gER, trajectory 1 with golden angle and extended readout