0774

Enlarged Perivascular Spaces in the Basal Ganglia Surround Arteries, not Veins1Athinoula A. Martinos Center, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard medical school, Charlestown, MA, United States, 2Department of Neurology, Otto-von-Guericke University, Magdeburg, Germany, 3German center for neurodegenerative diseases (DZNE), Magdeburg, Germany, 4Department of Biomedical Magnetic Resonance (BMMR), Institute for Physics, Otto-von-Guericke-University, Magdeburg, Germany, 5Institute of Cognitive Neurology and Dementia Research (IKND), Otto-von-Guericke University, Magdeburg, Germany, 6MassGeneral Institute for Neurodegenerative Disease, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Charlestown, MA, United States, 7Center for Behavioral Brain Sciences (CBBS), Magdeburg, Germany, 8Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience, University College London, London, United Kingdom, 9J. Philip Kistler Stroke Research Center, Department of Neurology, Massachusetts General Hospital/Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States, 10Department of Radiology, Leiden University Medical Center, Leiden, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Blood vessels, High-Field MRI, Histopathology

Fluid-filled perivascular spaces (PVS) surround brain vessels. Their enlargement is a common hallmark of cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD) and has been related to impaired clearance of toxic proteins from the brain. It is unclear whether PVS enlarge around arteries, veins, or both. Combining ultra-high resolution 7T MRI angiography, venography and histology, we show that in healthy controls and patients with CSVD, PVS enlarge around arteries more than veins within the basal ganglia. A better understanding of the anatomy and distribution of enlarged PVS can contribute to the understanding of perivascular clearance and disease mechanisms.

Introduction

Perivascular spaces (PVS) are fluid filled spaces surrounding brain vessels1. PVS can be pathologically enlarged and are then visible on T2-weighted MRI as hyperintense elongated stripes. They have been related to aging, hypertension, stroke, and inconsistently to cognitive impairment1,2. Furthermore, enlarged PVS (EPVS) are a common hallmark of cerebral small vessel disease (CSVD)1. Sporadic CSVD is driven by changes in the vessel’s wall due to arteriosclerosis – mainly in deep brain regions such as the BG - and accumulation of Amyloid-β (Aβ) in cerebral amyloid angiopathy (CAA), found in cortical and leptomeningeal vessels.EPVS have been implicated in the transport of toxic proteins out of the brain (perivascular clearance) and it has been hypothesized that their enlargement occurs when clearance is dysfunctional2. Pinpointing the anatomy of the EPVS and their relationship to measures of blood flow can help shed light on mechanisms of disease and on the routes of perivascular clearance. For example, it remains unclear if PVS enlarge around arteries or veins in the BG and whether increased pulsatility in the vessels is a driver of enlargement3,4.

This work addresses these knowledge-gaps in a cohort of cognitively normal elderly controls and CSVD patients. We combined in vivo ultra-high-resolution 7T MRI and histopathology to investigate whether PVS enlarge around arteries, veins, or both. Furthermore, we assessed whether pulsatility-index (PI) and blood flow velocity (MeanV=Vmean), measured by 7T phase-contrast MRI in the arteries of the BG, is associated with the respective EPVS measures.

Methods

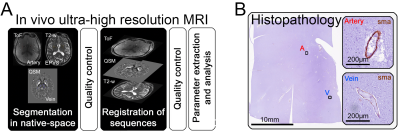

Forty-one participants (72.21y±5.59; mean±SD) were recruited by the German center for neurodegenerative diseases (DZNE) and the University Clinic of Magdeburg5. Each participant underwent a 3T (Siemens Verio) and, after inclusion in the study, a 7T MRI scan (Siemens Healthineers). Based on the 3T MRI, five CAA-cases were selected according to the Boston criteria 2.06. Twelve non-CAA CSVD showed microhemorrhages, a defining CSVD marker, in deep brain regions or mixed locations. Furthermore, twenty-four non demented healthy elderly controls without microhemorrhages and without other severe markers of CSVD were included. A 3T T2-weighted turbo-spin-echo-sequence (voxel-size: 1x1x2 mm) was used to visualize the EPVS. Arteries were detected on 7T time-of-flight-angiography (ToF) (voxel-size: 0.28mm isotropic), veins on quantitative susceptibility mapping (QSM), reconstructed from a 7T T2*-weighted 3D-gradient-echo-pulse-sequence (voxel-size: 0.35x0.35x1.5 mm), as previously described5. All segmentations were manually conducted in the axial plane within the BG-region of interest, using ITK-snap. To assess the spatial relation of EPVS and arteries versus veins, the 7T QSM (venography) and 3T T2-weighted-sequence (EPVS) were registered to the 7T-ToF (angiography) with a rigid registration that utilized a multi-resolution mutual information model. For each case, we calculated Dice-scores and Hausdorff-distances between EPVS and arteries, as well as EPVS and veins, to quantify their spatial relation. Additionally, EPVS number, mean EPVS volume, and total EPVS volume per case was extracted. Furthermore, single EPVS were associated with arteries or veins, based on the overlap ratio of the vessel with the EPVS. Overlapping vessel segments were approximated by fitting an ellipsoid (www.scikit-image.org) (Figure 1A).To calculate PI and Vmean in the small penetrating vessels of the BG, we used a previously described 2D phase-contrast (PC) sequence at 7T (voxel-size = 0.3x0.3x2 mm), in combination with multi-step image processing7.

Six autopsy cases (two representing each subgroup) were included from an autopsy-cohort of the Massachusetts General Hospital2. Tissue blocks of the BG were sampled from formalin fixed hemispheres, embedded in paraffin, and 6µm-thick adjacent sections were cut. Adjacent sections were stained with luxol-fast-blue (LHE) and underwent immunohistochemistry for smooth muscle actin (SMA). EPVS were identified on LHE-stained sections, and the corresponding vessel characterized as vein or artery on the adjacent SMA-stained section (Figure 1B).

Results

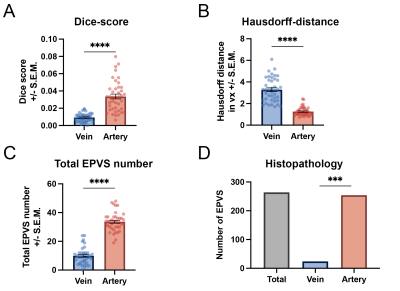

On the MRI, the Dice-score between EPVS and arteries was significantly higher than the one between EPVS and veins (Kruskal-Wallis H-Test: Mdnvein=0.01, Mdnartery=0.033, W=847, p<.0001; Figure 2A). The Hausdorff-distance between EPVS and arteries was significantly lower than between EPVS and veins (Kruskal-Wallis H-Test: Mdnvein=0.921mm, Mdnartery=0.351mm, W=-861, p<.0001; Figure 2B). Finally, we observed significantly more EPVS overlapping with arteries than with veins (Kruskal-Wallis H-Test: Mdnvein=10, Mdnartery=34, W=861, p<.0001; Figure 2C). Non-CAA CSVD patients had a higher number and higher mean EPVS volume compared to the other subgroups. In the histolopathology, we observed that the frequency of the EPVS related to arteries (254/264, 96%) was higher than that of EPVS related to veins (24/264, 4%) (Chi-Square test: n=619, χ2(1)=34.0, p<.001; Figure 2D).PI in the perforating arteries of the BG tended to be positively associated to total number of EPVS (Spearman's correlation: ρ=0.29, p=.080), and to total EPVS-volume (Spearman's correlation: ρ=0.31, p=.063). No relationship was found between EPVS-measures and Vmean.

Discussion

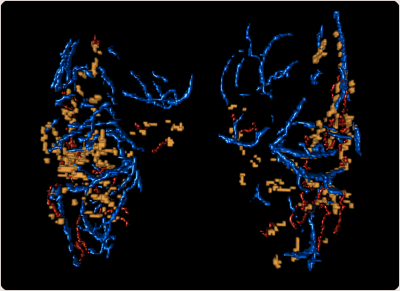

In the BG, our results show a closer spatial proximity of EPVS to arteries than to veins in high-resolution MRI (Figure 3D). In histopathology, EPVS were more frequently located around arteries. These findings are in line with previous works reporting spatial correlation of EPVS with arteries within centrum semiovale2,4, but no association with veins3. Conversely, the relationship between PI, Vmean and EPVS-measures showed no conclusive results. Our findings contribute to close knowledge-gaps about the development of EPVS and potentially help to decipher the routes of perivascular clearance in the human brain.Acknowledgements

We are very grateful to all participants who volunteered to take part in the study.

References

1. Wardlaw, J. M. et al. Perivascular spaces in the brain: anatomy, physiology and pathology. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 16, 137–153 (2020).

2. Perosa, V. et al. Perivascular space dilation is associated with vascular amyloid-β accumulation in the overlying cortex. Acta Neuropathol. 143, 331–348 (2022).

3. Jochems, A. C. C. et al. Relationship Between Venules and Perivascular Spaces in Sporadic Small Vessel Diseases. Stroke 51, 1503–1506 (2020).

4. Bouvy, W. H. et al. Visualization of perivascular spaces and perforating arteries with 7 T magnetic resonance imaging. Invest. Radiol. 49, 307–313 (2014).

5. Rotta, J.&Perosa V. et al. Detection of Cerebral Microbleeds With Venous Connection at 7-Tesla MRI. Neurology 96, e2048–e2057 (2021).

6. Charidimou, A. et al. The Boston criteria version 2.0 for cerebral amyloid angiopathy: a multicentre, retrospective, MRI-neuropathology diagnostic accuracy study. Lancet Neurol. 21, 714–725 (2022).

7. Geurts LJ et al. Higher pulsatility in cerebral perforating arteries in patients with small vessel disease related stroke: a 7T MRI study. Stroke; 50:62–68 (2019).

Figures

Figure 1. In vivo MRI and histopathology: A) Analysis of the MRI consisted in the segmentation of arteries, veins, and enlarged perivascular spaces (EPVS) in native space, registration of MRI sequences, and parameter extraction/analysis. Thorough visual quality control was conducted. B) The vessel associated with an EVPS was identified as an artery or vein based on the presence of smooth muscle actin (SMA)-positive cells (smooth muscle cells) within the vessel’s wall.

Figure 2. Spatial association of enlarged perivascular spaces with arteries and veins: A) Significantly larger Dice-score between EPVS and arteries versus EPVS and veins. B) Significantly lower Hausdorff-distance between EPVS and arteries versus EPVS and veins. C) Significantly larger total number of EPVS associated with arteries than EPVS with veins. D) Significantly higher frequency of EPVS associated with arteries than EPVS with veins in histopathology. *** p<.001 **** p<.0001

Figure 3. Example of a 3D illustration of the overlap between EPVS and vessels within the basal ganglia (BG): EPVS (yellow) show closer proximity to arteries (red) than to veins (blue).