0773

Enhanced Myelin Mapping based on Histology and MRI from the Same Subjects

Zifei Liang1, Choong Heon Lee1, Jennifer A. Minteer2, Yongsoo Kim2, and Jiangyang Zhang1

1Radiology, NYU Langone health, new york, NY, United States, 2Penn State University, Hershey, PA, United States

1Radiology, NYU Langone health, new york, NY, United States, 2Penn State University, Hershey, PA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Signal Representations, Brain, MR-histology

To infer cellular-level information from MR signals with high sensitivity and specificity is a challenging task. We previously demonstrated the feasibility of mapping myelin in the mouse brain based on multi-contrast MRI using deep learning, but the results were based on limited histological data and MRI data from separate cohorts. In this study, we acquired serial 2-photon and MRI data from the same mice and trained a neural network for mapping myelin. Our results demonstrated enhanced sensitivity and specificity compared to conventional MRI myelin markers, our previous network, and polynomial fitting.Introduction:

MRI is an important tool for the non-invasive mapping of brain structures and functions. Although numerous rich tissue contrasts have been developed, often targeting specific cellular components (e.g. axon and myelin), they remain indirect measurements and often lack sensitivity and specificity. Several approaches, including new MR contrast, multi-parametric, and modeling, have been reported, but the lack of co-registered histology and MRI data has been a bottleneck in pursuing the link between MRI signals and target cellular markers.We previously demonstrated the feasibility of training a deep learning network with co-registered multi-contrast MRI and histology to estimate myelin contents in the mouse brain based on multiple MR parameters1. The deep learning approach outperformed conventional MRI myelin markers in terms of sensitivity and specificity. One limitation of the previous study is that MRI and histology were obtained from different sources and inter-subject variations in myelination could introduce biases in the network.

To address this limitation, we acquired ex vivo MRI and serial 2-photon tomography (STPT) data from the brains of transgenic MOBP-eGFP mice, which co-express enhanced green fluorescence protein (eGFP) with myelin-associated oligodendrocyte basic protein (MOBP) in all myelinating oligodendrocytes and myelin sheaths. We investigated whether deep learning using data from the same animal can improve our estimation of myelin content from MRI signals.

Methods

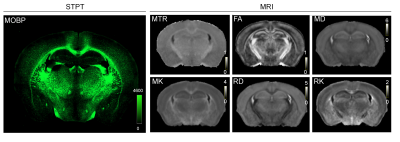

Animals, MRI, and STPT: MOBP-eGFP mouse brains at P14, P35, and P56 (n=4 at each stage) were perfusion fixed. Ex vivo MRI (Fig. 1) was acquired with the following parameters: T2-weighted (T2w) MRI: TE/TR = 50/1000 ms; magnetization transfer MRI: TE/TR = 28/800 ms, 5kHz offset frequency; diffusion MRI (dMRI): TE/TR = 30/350 ms, $$$δ/Δ$$$=5/15 ms, 30 directions, b=2/5 ms/um2. Several 3D STPT images were acquired with 1x1 um resolution (x,y) in every 50 um z serial sectioning and later downsampled to the same resolution as MRI (0.05 mm isotropic) and registered to MRI data from the same subject using coarse-to-fine linear and nonlinear alignments (Fig. 2)1. Mismatches in the forebrain region were mostly less than 0.1 mm.The MR-histology (MRH) network: We used data from part of the forebrain region for training and the rest for testing. The MRH network, as described previously2, was based on a CNN model with 64 hidden layers. The MRH-MOBP network was trained with 5 MRI parameters (T2, MTR, FA, MD, MK) as the input and the co-registered STPT-MOBP data as the target. A 3x3 patch size was used to accommodate residual mismatches between histology and MRI data. Approximately 100,000 such 3x3 patches were used to train the network.

Statistical analysis: From separate testing data, linear regression (MOBP and predicted MOBP values) produced R2, slope ($$$α$$$), and intercept ($$$β$$$), which were used to estimate sensitivity ($$$α$$$) and specificity ($$$α/(α+β)$$$) as in 2. Comparisons between different myelin estimators were performed using the F-test.

Results:

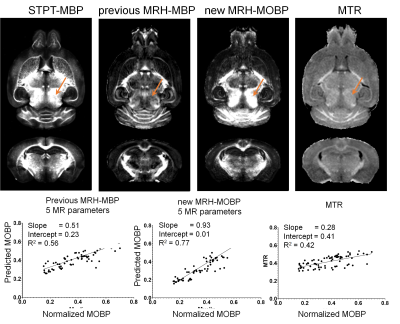

We first tested whether our reported MRH-MBP network, trained using MBP-stained histology and MRI data from different subjects, can still generate reasonable myelin estimation. The estimated MBP map (Fig. 3) had an overall contrast pattern comparable to the STPT-MOBP maps but underestimated myelin in the midbrain region (indicated by orange arrows). The sensitivity and specificity of the MRH-MBP were 0.51 and 0.69 (R2 =0.56, p<0.0001).As expected, MRH-MOBP trained using MRI and STPT-MOBP data from the same subjects showed improved sensitivity (0.93) and specificity (0.99) (R2=0.77, p<0.0001). The estimated myelin in the midbrain region was comparable to STPT-MOBP data. In comparison, the conventional MTR had lower sensitivity (0.28) and specificity (0.40) (R2=0.42).

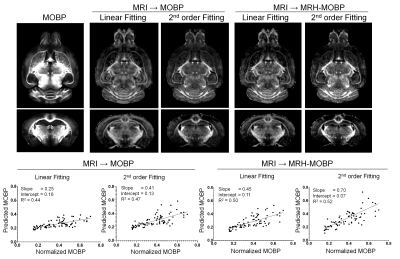

We then compared MRH-MOBP with polynomial fitting (Fig. 4). Myelin estimation based on results of directly fitting MR parameters to co-registered STPT-MOBP data showed limited improvement in sensitivity and specificity (sensitivity/specificity=0.25/0.61 for linear fitting, 0.41/0.76 for 2nd-order polynomial), likely due to remaining mismatches between MRI and histology. In comparison, myelin estimation based on results of fitting MR parameters to MRH-MOBP, showed more improvements (sensitivity/specificity=0.45/0.80 for linear fitting, 0.70/0.91 for 2nd-order polynomial) but still did not match MRH-MOBP.

Discussion

Our results have several implications: 1) the deep learning training with MRI and histology from the same animals confirm our previous report and provide high myelin specificity; 2) the use of multiple MRI parameters, each target unique aspects of myelin, also likely contributes to the higher sensitivity and specificity; 3) Comparing deep learning and polynomial fitting results suggests that the relationship between MRI signals and tissue myelin is more complex.Our study is not without its limitations: 1) the networks were based on ex vivo mouse data and may not apply to in vivo data due to the differences between in vivo and ex vivo MRI signals; 2) the resolution of MRI remains limited compared to histological data, and most importantly; 3) data from cases with complex neuropathology, e.g., inflammation and edema, are not present in the training dataset, which may limit the applicability of the technique for such cases.

Conclusion

MRI-based myelin mapping in the mouse brain with high sensitivity and specificity can be achieved using deep learning networks trained with co-registered MRI and histological data.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Liang, Z. et al. Virtual mouse brain histology from multi-contrast MRI via deep learning. Elife 11, doi:10.7554/eLife.72331 (2022).

2. Duhamel, G. et al. Validating the sensitivity of inhomogeneous magnetization transfer (ihMT) MRI to myelin with fluorescence microscopy. Neuroimage 199, 289-303, doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.05.061 (2019).

Figures

Figure

1: Representative STPT data and MR parameter maps from the same mouse brain.

Abbreviations: MTR: magnetization transfer ratio; FA: fractional anisotropy;

MD: mean diffusivity; MK: mean kurtosis; RD: radial diffusivity; RK: radial

kurtosis. The unit of MD and RD is um2/ms.

Figure

2: Representative horizontal (top) and axial (bottom) images of co-registered

MRI and STPT data. Landmarks were placed in the FA images and overlaid on

auto-fluroescence images to guide visual comparison. Good congruence was

achieved in the forebrain region.

Figure

3: The performance of the deep learning network (MRH-MBP) with respect to STPT-MOBP

signals and MTR maps. Top: Horizontal and axial images of STPT-MOBP signals,

myelin predictions using our previous MRH-MBP network based on 5 MR

parameters, newly trained MRH-MOBP

network based on the same MR parameters, and MTR. Bottom: Correlation analysis

showed improved myelin estimation by the newly trained MRH-MOBP network.

Figure

4: Myelin estimation based on results of linear and 2nd order

fitting of MR parameters to co-registered STPT-MOBP signals showed limited

improvements in myelin estimation compared to MRH-MOBP. Fitting MR parameters

to MRH-MOBP results, in comparison, showed more improvements in sensitivity and

specificity.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0773