0771

Synthesizing speech through a tube talker model informed by dynamic MRI-derived vocal tract area functions1Roy J. Carver Department of Biomedical Engineering, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States, 2Speech, Language and Hearing Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States, 3Janette Ogg Voice Research Center, Shenandoah University, Winchester, VA, United States, 4Electrical and Computer Engineering, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States, 5Department of Radiology, The University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Signal Modeling, Head & Neck/ENT

The vocal tract encompasses the airspace from the glottis (the space between the vocal folds) to the external lips. This irregular tube filters the glottal sound source, and is modulated by many structures (e.g. the tongue, lips, and velum) to produce speech sounds (e.g. vowels and consonants). In this work, we determine the preliminary feasibility of integrating vocal tract area functions derived from a recently proposed accelerated pseudo-3D dynamic speech MRI scheme to a parametric tube talker model to synthesize speech.Purpose:

The vocal tract encompasses the airspace from the glottis (the space between the vocal folds) to the external lips. This irregular tube filters the glottal sound source, and is modulated by many structures (e.g. the tongue, lips, and velum) to produce speech sounds (e.g. vowels and consonants). Dynamic speech MRI is a powerful modality to safely assess vocal tract kinematics. Sparse sampling and spatio-temporal constrained reconstruction MRI methods have demonstrated significant improvements in 3D dynamic vocal tract MRI. Spatial resolutions ranging from isotropic 2mm to 2.4 mm x 2.4 mm x 5-6mm; and temporal resolution ranging from 10 ms to 78 ms have recently been reported to image repeated or fluent speech [1-4]. Measuring vocal tract kinematics in this manner may have useful applications, particularly in improving parametric models that synthesize speech. In this work, we determine the preliminary feasibility of integrating vocal tract area functions derived from a recently proposed accelerated pseudo-3D dynamic speech MRI scheme [4] to a parametric vocal tract model (aka the TubeTalker model [5-6]) to synthesize speech.Methods:

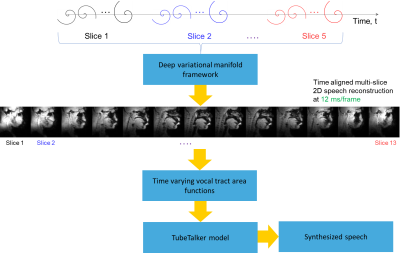

Experiments were performed on a GE 3 Tesla Premier scanner equipped with high performance gradients coils (80 mT/m, maximal slew rate 150 T/m/s). Two volunteers were scanned using a custom 16 channel vocal tract coil. A 2D gradient echo based variable density spiral sequence was implemented with 335 readout points, readout duration ~ 1.3 ms at a spatial resolution of 2.4mm2 and field of view of 20 cm2. The sequence was prescribed in the sagittal orientation with a slice thickness of 6 mm; TR ~ 6ms, flip angle = 5 degrees. The sequence was run to sequentially acquire 13 slices in the left-right direction in the sagittal orientation. 2700 spiral arms (~16 seconds of data) were acquired for one slice before acquiring raw data for the next slice. Total acquisition time was ~ 3.5 minutes. Subject 1 repeated the phrase /za: na: za: loo: lee: la:/. Subject 2 repeated the phrase, “He had a rabbit”. For the second subject, concurrent audio was acquired, and denoised to reduce the MRI acoustic noise [7]. As demonstrated in figure 1, the raw k-space data from sequentially acquired slices was fed to an unsupervised generative dynamic model [4] capable of reconstructing a time-aligned multi-slice dataset at a time resolution of 12ms/frame (aka pseudo 3D dynamic dataset). Reconstruction parameters of the generative model were fixed as previously reported [4]. After reconstruction, oblique cuts for every time frame across the vocal tract spanning from the lips to the glottis were extracted. Seed growing segmentation in these oblique cuts was done to quantitate the time varying vocal tract area functions (VAFs). Based on the anatomy of the subject, the number of oblique cuts varied. We considered 77, and 84 oblique respectively for subject 1 and subject 2. The VAFs were subsequently fed to the tube talker model which synthesized speech. For subject 1, we qualitatively analyzed the postures of the TubeTalker model’s output and correlated to the expected postures during the production of the phonemes. For subject 2, we correlated the audio spectrogram of the TubeTalker’s output to the acquired audio spectrogram.Results:

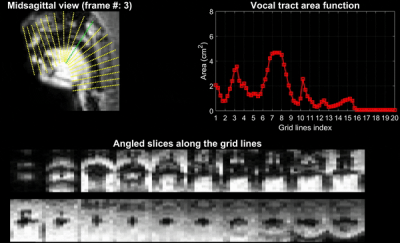

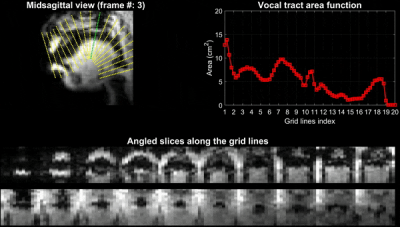

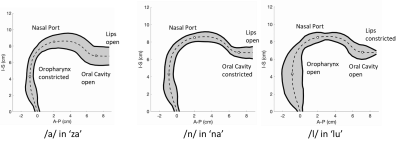

Figure 2 and 3 respectively show the /za: na: za: loo: lee: la:/ utterance by speaker 1; and the “He had a rabbit utterance” by speaker 2. Shown are the midsagittal orientation along with representative oblique cuts along the vocal tract. Note that we only show a fraction of the oblique cuts for brevity, although a much finer grid spacing oblique cuts were fed to the TubeTalker model. The kinematics of the deforming vocal tract can be appreciated by the constrictions represented in the corresponding VAFs.Figure 4 shows representative snapshots of the TubeTalker output demonstrating the vocal tract pose during production of different sounds. We observe the TubeTalker to represent the vowel and consonant place of articulation reasonably well. This is evident during production of /a/ in ‘za’ where the lips are open and oropharynx is constricted; tongue tip constriction for the /n/ sound, opening of the oropharynx during loo sound. However, the consonant sounds appear to sound like an “l’’ because the constrictions donot come to full closure.

Figure 5 shows the spectrogram from the TubeTalker simulated speech (first two rows), and the spectrogram of the acquired audio after acoustic noise removal. We note although the energy in the frequencies of the spectrogram donot align up exactly, the uttered phrase of “He had a rabbit” appear to be present.

Conclusion:

We have demonstrated the feasibility of speech synthesis based on feeding 3D dynamic vocal tract MR imaging data to a parametric TubeTalker model. A work in progress is to optimize the model parameters of the TubeTalker model to adjust for the distinction between the consonant sounds, and to better perceive continuous phrases.Acknowledgements

This work was conducted on an MRI instrument funded by 1S10OD025025-01References

[1] Lim, Y., Zhu, Y., Lingala, S. G., Byrd, D., Narayanan, S., & Nayak, K. S. (2019). 3D dynamic MRI of the vocal tract during natural speech. Magnetic resonance in medicine, 81(3), 1511-1520.

[2] Zhao, Z., Lim, Y., Byrd, D., Narayanan, S., & Nayak, K. S. (2021). Improved 3D real‐time MRI of speech production. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine, 85(6), 3182-3195.

[3] Jin, R., Shosted, R. K., Xing, F., Gilbert, I. R., Perry, J. L., Woo, J., ... & Sutton, B. P. (2022). Enhancing linguistic research through 2‐mm isotropic 3D dynamic speech MRI optimized by sparse temporal sampling and low‐rank reconstruction. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine.

[4] Rusho, R. Z., Zou, Q., Alam, W., Erattakulangara, S., Jacob, M., & Lingala, S. G. (2022). Accelerated Pseudo 3D Dynamic Speech MR Imaging at 3T Using Unsupervised Deep Variational Manifold Learning. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention (pp. 697-706). Springer, Cham.

[5] Story, B. H. (2005). A parametric model of the vocal tract area function for vowel and consonant simulation. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America, 117(5), 3231-3254.

[6] Story, B. H. (2011). TubeTalker: An airway modulation model of human sound production. In Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Performative Speech and Singing Synthesis (pp. 1-8). Vancouver, Canada: P3S 2011.

[7] Vaz, C., Ramanarayanan, V., & Narayanan, S. S. (2013, August). A two-step technique for MRI audio enhancement using dictionary learning and wavelet packet analysis. In INTERSPEECH (pp. 1312-1315).

Figures