0739

Double Pulsed Field Gradient Diffusion MRI of skeletal muscle is sensitive to muscle microstructure1UC San Diego, La Jolla, CA, United States, 2University of Arizona, Tuscon, AZ, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Muscle, Diffusion/other diffusion imaging techniques

Single pulsed field gradient (sPFG) diffusion MRI (dMRI) is a commonly researched tool to monitor changes in muscle microstructure associated with injury. Double pulsed field gradient (dPFG) dMRI has been used to characterize microstructure of neural tissues, but is not commonly applied to skeletal muscle. This study demonstrates both in silico and in vivo applications of dPFG dMRI to assess changes in muscle microstructure that are related to muscle function (e.g. fiber diameter). Additionally, a novel method for analyzing dPFG data called Diffusion Tensor Subspace Imaging (DiTSI) demonstrates high sensitivity to quantifiable biomarkers of muscle microstructure.Introduction

Muscle fiber size is an important microstructural component of muscle health that is strongly predictive of force generating capacity1. Many groups have utilized diffusion MRI (dMRI) to noninvasively assess muscle microstructure in response to training, pathology, and injury. Single pulsed field gradient (sPFG) dMRI pulse sequences are the workhorse of diffusion imaging in skeletal muscle and have yielded important information about the relationship between restricted diffusion and skeletal muscle microstructure, but there is no consensus on the precise correlation between these measures. Double pulsed field gradient (dPFG) dMRI is a technique that implements two bipolar pairs of diffusion encoding gradients and has been used to characterize microscopic anisotropy of neural tissues2. There is limited use of dPFG sequences to characterize the relationship between muscle microstructure and diffusion-based anisotropy, which may enhance sensitivity to muscle fiber size. Recently, we have developed a novel method for analyzing dPFG data - Diffusion Tensor Subspace Imaging (DiTSI) - as part of the Joint Estimation Diffusion procedure3 that provides greater sensitivity to tissue microstructure. The goal of this study is to investigate the sensitivity of dPFG dMRI to muscle microstructure in normal and injured muscle using DiTSI.Methods

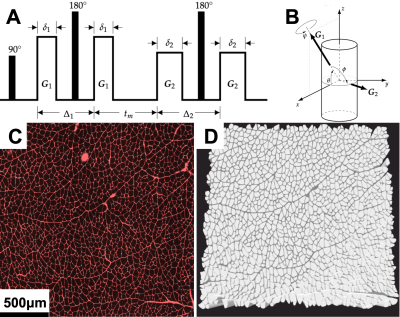

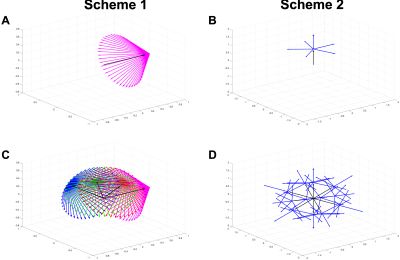

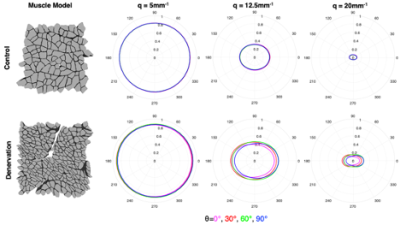

DifSim, an environment for simulating dMRI experiments in arbitrarily complex models of microstructure, was used to simulate a dPFG pulse sequence in models of normal, regenerating (cardiotoxin) and atrophic (surgical denervation, botox, tenotomy) skeletal muscle generated from histology4–7(Fig 1). Two sampling schemes were investigated: 1.) A radial sampling scheme where the first bipolar gradients were at θ = {0°, 30°, 60°, 90°}; and the second bipolar gradients were at 45 different angles φ = 135°; ψ = {0°, 8°, 16°, … 344°, 352°} at 3 different q values (5mm-1, 12.5mm-1, 20mm-1) and 2.) A collinear + orthogonal vector scheme, where the first bipolar gradients were along 12 collinear directions, followed by 6 orthogonal directions (Fig. 2). From scheme 2, we construct two quantities of lower dimensionality but physical significance: the radial and angular standard deviations of Φ3:$$σ_{R1,R2} \equiv σ(R_1,R_2) = \frac{1}{4\pi}(\displaystyle \int \int dΩ_1 dΩ_2[\phi(r,R_1,R_2)-\bar{\phi}_Ω]^2)^\frac{1}{2}$$

$$σ_{Ω1,Ω2} \equiv σ(Ω_1,Ω_2) = \frac{1}{R_{max}}(\displaystyle \int \int dR_1 dR_2[\phi(r,Ω_1,Ω_2)-\bar{\phi}_R]^2)^\frac{1}{2} $$

where $$$Ω=(\theta,\phi)$$$ and $$$\bar{\phi}_R$$$ and $$$\bar{\phi}_Ω$$$ are radial and angular averages of the spin density function $$$\phi(r,R_1,R_2)$$$

$$\phi_R(Ω_1,Ω_2)=\frac{1}{R^2_{max}} \displaystyle \int \int dR_1dR_2\phi(r,R_1,R_2)$$

$$\phi_Ω(R_1,R_2)=\frac{1}{(4\pi)^2} \displaystyle \int \int dΩ_1dΩ_2\phi(r,R_1,R_2)$$

The radial and angular variances $$$σ_{R1,R2}$$$ and $$$σ_{Ω1,Ω2}$$$ characterize diffusion properties at different radial and angular scales, and contain a great deal of information. However, they are multidimensional tensors and it is useful to derive average quantities of lower dimensionality that can be overlayed to easily discern spatial variations in diffusion properties. Averaging the radial variances matrix over all NxN radii provides the scalar quantities, spherical anisotropy (SA) and radial anisotropy3:

$$<σ_R>=\displaystyle \intσ(R_1,R_2)dR_1dR_2$$

$$<σ_Ω>=\displaystyle \intσ(Ω_1,Ω_2)dΩ_1dΩ_2$$

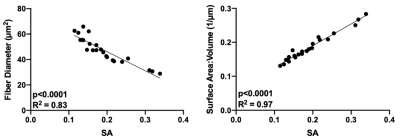

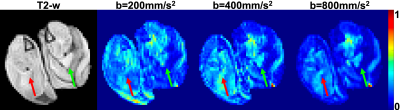

Linear regression was used to relate SA to muscle microstructural measurements (fiber size, surface area to volume ratio (S/V)). As a proof of principle, a rat model of muscle hypertrophy (synergist ablation) was generated and scanned on a Bruker 7T with b-values of 200s/mm2, 400s/mm2, and 800s/mm2, using sampling scheme 2 and SA maps were calculated.

Results

From sampling scheme 1, the dPFG signal plotted over a range of relative orientations (G2) for each of the gradient vectors G1 demonstrates an isotropic diffusion signal for control muscle (Fig. 3). However, for atrophic muscle, a more anisotropic relationship between the diffusion signal was found, that was exacerbated at higher q-values (Fig 3). From sampling scheme 2, the SA of each muscle model was calculated and the relationship between muscle microstructure and SA was computed (Fig 4). Excellent agreement between SA and muscle fiber size (R2=0.83) and S/V (R2=0.97) was observed. To demonstrate translatability, a muscle hypertrophy model was scanned using a dPFG sequence, and revealed decreased spherical anisotropy in the hypertrophic muscle, which was predicted from simulated experiments (Fig. 5).Discussion

The goal of this study was to explore the sensitivity of dPFG dMRI pulse sequences to microstructural changes associated with muscle injury. Sampling scheme 1 detected anisotropy in the diffusion signal in injured muscle that was not present in control muscle; with denervation injuries, muscle fibers appear more angular8. From sampling scheme 2, SA yielded excellent correlation with both muscle fiber diameter and S/V. Muscle fiber size is directly related to isometric force generating capacity and thus is an important biomarker of muscle health. S/V is not traditionally a biomarker used to characterize muscle, however it is an output variable of the Random Permeable Barrier Model – a time dependent dMRI model used to estimate muscle microstructure from dMRI experiments9. Future work should investigate the relationship between S/V and muscle fiber isometric force generating capacity. Finally, a major hurdle with dPFG experiments is pulse sequence design and implementation. Due to the short T2 of skeletal muscle, it is necessary to rapidly apply diffusion encoding gradients in order to minimize TE. This study demonstrates that applying dPFG pulse sequences to study skeletal muscle is feasible and sensitive to microstructural differences between muscles.Conclusion

dPFG dMRI pulse sequences are sensitive to discerning between healthy and injured skeletal muscle. DiTSI analysis provides a quantitative biomarker (SA) that correlates with a key biomarker of muscle function, fiber size.Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by grants from the NIH (R01AR070830-01)References

1. Ward SR, Minamoto VB, Suzuki KP, Hulst JB, Bremner SN, Lieber RL. Recovery of rat muscle size but not function more than 1 year after a single botulinum toxin injection. Muscle Nerve 2018; 57:435–441.

2. Henriques RN, Palombo M, Jespersen SN, Shemesh N, Lundell H, Ianuş A. Double diffusion encoding and applications for biomedical imaging. J. Neurosci. Methods 2021.

3. Frank LR, Zahneisen B, Galinsky VL. JEDI: Joint Estimation Diffusion Imaging of macroscopic and microscopic tissue properties. Magn. Reson. Med. 2020; 84:966–990.

4. Berry DB, Regner B, Galinsky V, Ward SR, Frank LR. Relationships between tissue microstructure and the diffusion tensor in simulated skeletal muscle. Magn. Reson. Med. 2018; 80:317–329.

5. Berry DB, Englund EK, Galinsky V, Frank LR, Ward SR. Varying diffusion time to discriminate between simulated skeletal muscle injury models using stimulated echo diffusion tensor imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. 2021; 85:2524–2536.

6. Balls GT, Frank LR. A simulation environment for diffusion weighted MR experiments in complex media. Magn. Reson. Med. 2009; 62:771–8.

7. Baxter GT, Frank LR. A computational model for diffusion weighted imaging of myelinated white matter. Neuroimage 2013; 75:204–212.

8. Baloh RH, Rakowicz W, Gardner R, Pestronk A. Frequent atrophic groups with mixed-type myofibers is distinctive to motor neuron syndromes. Muscle Nerve 2007; 36:107–110.

9. Novikov DS, Fieremans E, Jensen JH, Helpern JA. Random walks with barriers. Nat. Phys. 2011; 7:508–514.

Figures