0733

Pelvic organs prolapse recurrence after surgery using static and dynamic MRI1The First Central Clinical College of Tianjin Medical University, Tianjin, China, 2Department of Radiology, Tianjin First Central Hospital, School of Medicine, Nankai University, Tianjin, China, 3Philips healthcare, Beijing, China

Synopsis

Keywords: Pelvis, Pelvis, Static-Dynamic MR; pelvic organs prolapse; levator ani muscle; pelvic floor reconstruction surgery; recurrent risk

As high as 54% is the anatomical recurrence rate following hysterectomy with anterior and posterior vaginal wall restoration for pelvic organ prolapse (POP). The levator ani muscle (LAM) is the primary pelvic floor support system. Using static and dynamic MRI, we investigated the association between the morphology and function of LAM and the postoperative recurrence of POP. Risk factors for the recurrence of POP included the thickness and injury of the LAM at rest, the H line, the M line, and the size of the levator hiatus at rest and strain, as well as the variation of the levator hiatus during the Valsalva maneuver.

Purpose

The most common and primary surgical therapy for pelvic organs prolapse (POP) is hysterectomy with anterior and posterior vaginal wall restoration. However, this operation does not heal the levator ani muscle (LAM), the primary supporting power of the pelvic floor. Therefore, this operation has a significant recurrence risk, with a rate of 31.3% five years following surgery. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is a good imaging method for visualizing and evaluating LAM, including its shape and function. In contrast, clinical evaluations and ultrasounds are unavailable. We employed static and dynamic MRI to evaluate the preoperative morphology and function of the LAM in patients with POP and to investigate if these characteristics are linked with POP recurrence after pelvic floor reconstruction surgery.Method

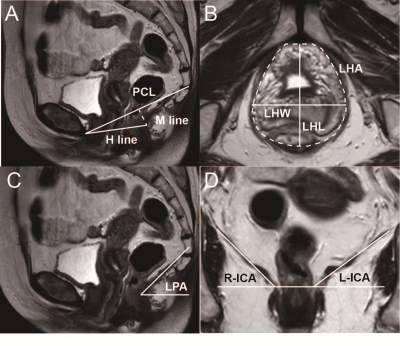

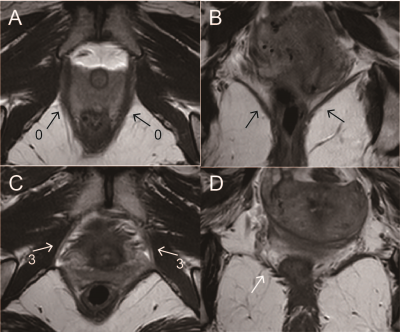

From March 2015 to July 2021, 38 patients with POP detected by clinical pelvic organ prolapse quantitative evaluation (POP-Q) at our institution were included. The following inclusion criteria were required: 1) hysterectomy and anterior and posterior vaginal wall restoration; 2) full and detailed clinical history; and 3) static and dynamic pelvic floor MRI within two weeks before surgery. The following were the criteria for exclusion: 1) non-compliance with the surgical procedure; 2) poor imaging quality; and 3) previous pelvic surgery. For the MR examination, a 3T MR scanner was used (Philips, Ingenia, Netherlands). Static MRI utilized FSE sequence (TR = 4110ms; TE = 102ms; matrix = 320 x 256; FOV = 260mm x 260mm; section thickness = 3mm; gap = 0.3mm; averages 2 times). Dynamic MRI used B-FFE (TR = 5.3ms; TE = 2.4ms; matrix = 280 × 376; FOV = 300mm × 300mm; section thickness = 5mm; gap = 0.5mm; averages 1 time) and SSFSE (TR = 4818ms; TE = 95ms; matrix = 2600 x 260; FOV = 280mm × 280mm; section thickness = 6mm; gap = 0.6mm; averages 2 times) sequences. Two radiologists evaluated the LAM morphological and functional measurements on the MRIs, including the puborectalis muscle thickness (PRT), the iliococcygeus muscle thickness (ICT), the levator ani muscle injury score (LAMIS), the H line, the M line, the length (LHL), width (LHW), and area (LHA) of the levator hiatus, the levator plate angle (LPA), and the iliococcygeal angle (ICA) (Figure 1-2). The included patients had gynecological physical examinations, pelvic floor MRI examinations, and pelvic floor distress inventory questionnaire-20 (PFDI-20) questionnaires more than six months following surgery. Based on their postoperative recurrence status, they were divided into two groups, with 16 patients in the recurrence group and 22 cases in the non-recurrence group. Using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC), the consistency of the LAM measurements made by two observers was evaluated. Using univariate analysis, the clinical features and preoperative LAM states measured in the recurrence group and the non-recurrence group were compared using independent samples t test, Mann-Whitney U test, or chi-square test. Using the Spearman correlation coefficient, the relationship between the LAM measures and the postoperative PFDI-20 scores were analyzed. P < 0.05 indicated a statistically significant difference.Result

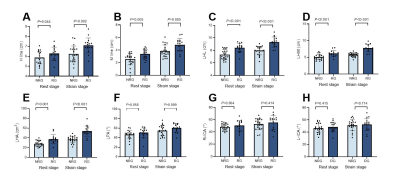

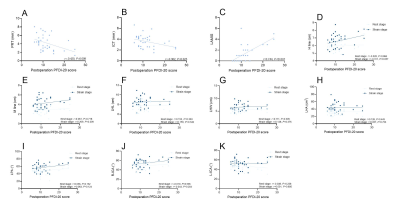

Two observers assessed LAM with a high degree of consistency (ICC: 0.757 ~ 0.900). The recurrence group had higher postoperative PFDI-20 scores than the non-recurrence group (P = 0.027). In the recurrence group, bilateral PRT and ICT were lower than in the non-recurrence group (all P < 0.001). In the recurrence group, both the incidence of LAM damage and the severity of LAM injury were greater (Figure 3). In addition, the H line and M line at rest and strain were lengthened, and the LHL, LHW, and LHA were increased in the recurrent group (Figure 4). All of the aforementioned differences were statistically significant (all P < 0.005). The connection between the LAMIS and the postoperative PFDI-20 score was significant (r = 0.744, P < 0.001). The correlation between the PRT and ICT and the postoperative PFDI-20 score were negative. (r = -0.420, P < 0.05; r = -0.362, P < 0.05, respectively) (Figure 5).Conclusion

Preoperative LAM status was related with recurrence following pelvic floor reconstruction surgery in patients with POP. Risk variables for recurrence of POP were the thickness and injury of LAM at rest, the H line, M line, and size of levator hiatus at rest and strain, and the alteration of levator hiatus during the Valsalva maneuver. The LAM thickness and injury scores were linked with postoperative PFDI-20 scores, such that the thinner the LAM and the more serious the injury, the more severe the postoperative pelvic floor dysfunction symptoms and the worse the therapeutic efficacy.Acknowledgements

We sincerely thank the participants in this study.

References

[1] WEINTRAUB A Y, GLINTER H, MARCUS-BRAUN N. Narrative review of the epidemiology, diagnosis and pathophysiology of pelvic organ prolapse[J]. Int Braz J Urol, 2020,46(1):5-14.

[2] WILKINS M F, WU J M. Lifetime risk of surgery for stress urinary incontinence or pelvic organ prolapse[J]. Minerva Ginecol, 2017,69(2):171-177.

[3] ABDEL-FATTAH M, FAMILUSI A, FIELDING S, et al. Primary and repeat surgical treatment for female pelvic organ prolapse and incontinence in parous women in the UK: a register linkage study[J]. BMJ Open, 2011,1(2): e000206.

[4] DIETZ H P. Ultrasound in the assessment of pelvic organ prolapse[J]. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol, 2019,54:12-30.

[5] CHAMIé L P, RIBEIRO D, CAIADO A, et al. Translabial US and Dynamic MR Imaging of the Pelvic Floor: Normal Anatomy and Dysfunction[J]. Radiographics, 2018,38(1):287-308.

[6] DE ARRUDA G T, DOS SANTOS HENRIQUE T, VIRTUOSO J F. Pelvic floor distress inventory (PFDI)-systematic review of measurement properties[J]. Int Urogynecol J, 2021,32(10):2657-2669.

[7] JAKUS-WALDMAN S, BRUBAKER L, JELOVSEK J E, et al. Risk Factors for Surgical Failure and Worsening Pelvic Floor Symptoms Within 5 Years After Vaginal Prolapse Repair[J]. Obstet Gynecol, 2020,136(5):933-941.

[8] SANTIS-MOYA F, PINEDA R, MIRANDA V. Preoperative ultrasound findings as risk factors of recurrence of pelvic organ prolapse after laparoscopic sacrocolpopexy[J]. Int Urogynecol J, 2021,32(4):955-960.

[9] SCHACHAR J S, DEVAKUMAR H, MARTIN L, et al. Pelvic floor muscle weakness: a risk factor for anterior vaginal wall prolapse recurrence[J]. Int Urogynecol J, 2018,29(11):1661-1667.

[10] TIRUMANISETTY P, PRICHARD D, FLETCHER J G, et al. Normal values for assessment of anal sphincter morphology, anorectal motion, and pelvic organ prolapse with MRI in healthy women[J]. Neurogastroenterol Motil, 2018,30(7): e13314.

[11] BITTI G T, ARGIOLAS G M, BALLICU N, et al. Pelvic floor failure: MR imaging evaluation of anatomic and functional abnormalities[J]. Radiographics, 2014,34(2):429-448.

Figures

Fig.1 A schematic of LAM related to morphology on MRI. A, Axial T2WI, bilateral PRT (shown in short line); B, Coronal T2WI, bilateral ICT (shown in short line). C-H, MRI-based LAM injury score; C, D, Axial and coronal T2WI, bilateral LAM run continuously without injury, recorded as 0, 0; E, F, Axial and coronal T2WI, the right LAM is missing muscle fibers, the area is less than 50%, the left LAM is thin and blurred, the area is greater than 50%, recorded as 1, 2; G, H, Axial and coronal T2WI, the right LAM runs continuously without injury, the left LAM is completely fractured, recorded as 0, 3.

Fig.2 A schematic of LAM related to function on MRI. A, Mid-sagittal T2WI, the “H line” is measured from the inferior pubic symphysis to the posterior anorectal junction; the “M line” is drawn perpendicularly down from the PCL to the posterior H-line; B, Inferior pubic symphysis' axial T2WI, LHA is drawn with anteriorly the inferior of the pubis, posteriorly the inner of puborectalis muscle; C, Mid-sagittal T2WI, LPA is measured between the levator plate and the horizontal line; D, Perineal coronal T2WI, ICA is measured between the iliococcygeal muscle and the pelvic horizontal plane.

Fig.3 Comparison of LAM morphological images of POP patients with and without recurrence. A, B, Axial and coronal T2WI, bilateral puborectalis and iliococcygeus muscles are wide and continuous in the non-recurrent group of POP patients (shown by black arrows); C, D, Axial and coronal T2WI, bilateral puborectalis muscle and the right iliococcygeus muscle are thinned and atrophied in the recurrent group of POP patients, bilateral puborectalis muscle are broken at the pubic bone attachment (shown by white arrows), and the right iliococcygeus muscle is slender and discontinuous.

Fig.4 A histogram of LAM functional measurements between groups with and without recurrence. Note: NRG = non-recurrence group. RG = recurrence group.

Fig.5 A scatterplot of correlation between postoperative PFDI-20 scores and LAM functional measurements.