0724

Comparing the effectiveness of 1D versus 2D navigated respiratory-correlated 4D-MRI acquisitions for radiotherapy guidance

Katrinus Keijnemans1, Pim Borman1, Bas Raaymakers1, and Martin Fast1

1Department of Radiotherapy, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

1Department of Radiotherapy, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Lung, Radiotherapy, 4D-MRI, Respiratory navigator

Accurate characterization of internal anatomical motion is essential for correctly guiding free-breathing radiotherapy treatments on the MR-linacs. Respiratory-correlated 4D-MRI can potentially provide this crucial information during each treatment session. We acquired a 1D respiratory navigator (1D-RNAV) interleaved with simultaneous multi-slice (SMS) images, yielding a concurrent 2D navigator (2D-RNAV). Respiratory-correlated 4D-MRIs were obtained with the 1D and 2D internal navigator surrogate signals, and the amount of missing anatomical data was quantified. Using the 1D-RNAV signal yielded fewer missing data in respiratory-correlated 4D-MRIs. Improving breathing regularity using biofeedback did not substantially influence the choice of navigator.Purpose

Acquiring a respiratory-correlated 4D-MRI on an MR-linac characterizes the internal anatomical motion and could thus improve guidance for free-breathing radiotherapy treatmentsa. While the benefits of internal navigators over external surrogate signals (e.g., belts) are well studied, the advantages and disadvantages of 1D versus 2D internal navigators are poorly understood. Here, we propose to directly compare the two navigator signals by adding a 1D respiratory navigator (1D-RNAV) to our previously developed simultaneous multi-slice (SMS) accelerated 4D-MRI sequenceb, for which the liver-lung interface motion yields a 2D navigator (2D-RNAV). First, we compare the concurrently acquired 1D and 2D navigation signals, and assess their respective impact on the derived respiratory-correlated 4D-MRIs. Second, we use the 1D-RNAV for real-time visual biofeedback during 4D-MRI acquisitions to regularize breathing and to evaluate the effect of breathing regularity on the navigators and derived 4D-MRIs.Methods

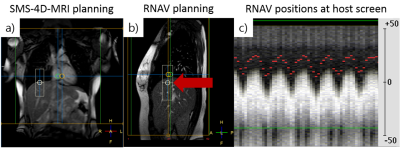

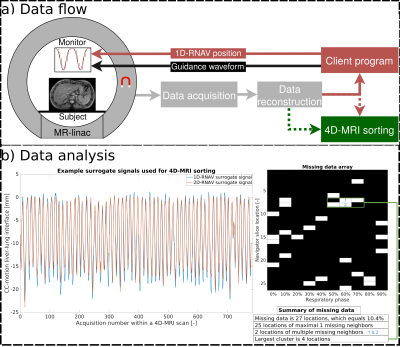

Data were acquired in nine healthy volunteers on a 1.5 T Unity MR-linac (Elekta AB, Sweden). A SMS accelerated T2-weighted turbo spin echo 4D-MRI sequenceb was interleaved with a cylindrical RNAV acquisition on the liver-lung interface, which had a length of 100 mm (CC) and a diameter of 30 mm (Figure 1). For the 4D-MRI sequence, two coronal slices were acquired simultaneously and SMS slices were repeatedly acquired in an interleaved order covering an image stack of 52 slices (Table 1). The RNAV acquisition rate was 343 ms.After applying an edge-preserving median filter on the acquired RNAV data, the 1D-RNAV position was estimated on the spectrometer using edge-detection and then sent to the reconstructor. When received in the reconstructor, the 1D-RNAV position was streamed using in-house software (ReconSocketc) to a client program. Reconstructed SMS images were saved for retrospective 4D-MRI sorting (Figure 2a).

The 2D-RNAV positions were estimated by template-matching (normalized cross-correlation) on the liver-lung interface, which was visible in the central 26 navigator slices (half the image stack). An intrinsic 4D-based motion model was used to account for nonuniform cranial-caudal motion across the navigator slice locationsb. The coronal slice intersecting the 1D-RNAV acquisition was used as reference location for scaling. Cranial-caudal liver-lung interface motion thus yielded a 2D-RNAV surrogate signal.

The 1D-RNAV and 2D-RNAV signals were compared (after temporal alignment) by calculating the root mean square error (RMSE). The quality of the respiratory-correlated 4D-MRIs was determined by quantifying the percentage missing anatomical data in the respiratory-correlated 4D-MRIs. Missing data is defined here as empty entries in the slice-phase matrix (Figure 2b), i.e., anatomy that was not captured in certain respiratory phases. Missing data can be approximated from neighboring slices and phases, but this becomes more difficult the larger the cluster of missing data becomes.

To investigate the impact of reduced breathing variability on the navigator concurrence, for some experiments the 1D-RNAV position was also displayed as biofeedback together with a guidance waveform on an in-room monitor and saved for analysis (Figure 2a). The guidance waveform was a cosine4 with a subject-specific peak-to-peak amplitude and period derived from an unguided acquisition. In a previous study we demonstrated that our biofeedback system reduces median respiratory variability by 23% (amplitude) and 60% (period).

Per volunteer, four 4D-MRI acquisitions were performed: an unguided 4D-MRI acquisition to obtain the subject-specific ‘natural’ peak-to-peak amplitude and period (4:27 min), a guided acquisition with the subject-specific peak-to-peak amplitude and period (5:12 min), a guided acquisition with 50% increased period to evaluate adaptability (5:12 min), and a longer guided acquisition with the subject-specific parameters to evaluate the ability to maintain regular breathing (10:24 min).

Subject-specific parameters were derived by splitting the saved 1D-RNAV signal into individual breathing cycles, and calculating the median amplitude and period. For the longer guided acquisition, a sliding window analysis approach was performed (4:27 min window size), resulting in 36 4D-MRIs.

Results

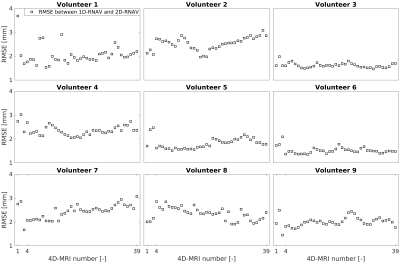

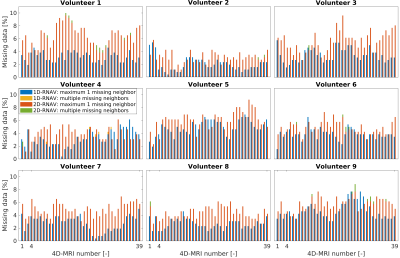

For unguided acquisitions, a median (min-max) RMSE of 2.0 (1.6-3.7) mm was found between the 1D-RNAV and 2D-RNAV surrogate signals, and a median (min-max) RMSE of 2.0 (1.4-3.1) mm was found for guided acquisitions (Figure 3). We observed that the 2D-RNAV consistently provided lower estimates of the peak-to-peak amplitude.For the 1D-RNAV, a median (min-max) missing data percentage of 3.5 (1.5-5.8)% was found while a median (min-max) percentage of 4.6 (1.7-6.2)% was found for the 2D-RNAV for the unguided acquisitions. For acquisitions with visual guidance, a median (min-max) missing data percentage of 3.5 (0.4-7.7)% was found for the 1D-RNAV and 5.0 (1.1-10.0)% for the 2D-RNAV. Figure 4 shows that the 1D-RNAV signal resulted in missing data with multiple neighbors for volunteer 4, while this occurred in seven volunteers for the 2D-RNAV signal.

The largest cluster of missing data in the unguided data was 3 for the 1D-RNAV and 5 for the 2D-RNAV, which reduced to 2 and 4 respectively if the 4D-MRIs were acquired with biofeedback.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our study directly compared concurrently acquired 1D and 2D internal navigators used for respiratory-correlated 4D-MRI. The 2D-RNAV returns lower estimates of the peak-to-peak respiratory amplitude, likely related to the relatively coarse voxel size. We also found fewer missing data when the 1D-RNAV signal was used to sort 4D-MRIs. Visual biofeedback during 4D-MRI acquisitions markedly improved breathing regularity but did not influence the amount of missing data or navigator selection.Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge funding by the Dutch Research Council (NWO) through project no. 17515 (BREATHE EASY). We acknowledge research agreements with Elekta AB (Stockholm, Sweden) and Philips Healthcare (Best, The Netherlands).References

a. B Stemkens et al. Nuts and bolts of 4D-MRI for radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 2018;63(21): 21TR01b. K Keijnemans et al. Simultaneous multi-slice accelerated 4D-MRI for radiotherapy guidance. Phys Med Biol. 2021;66(9):095014

c. P T S Borman et al. ReconSocket: a low-latency raw data streaming interface for real-time MRI-guided radiotherapy. Phys Med Biol. 2019;64(18):185008

Figures

Figure

1: Planning of the simultaneous multi-slice (SMS)

accelerated 4D-MRI (orange box) and respiratory navigator (1D-RNAV, white cylinder).

a) The 4D-MRI field-of-view included the thorax and upper abdomen. b) The RNAV

(red arrow) was positioned at the liver-lung interface in the end-exhale state

on a sagittal 2D-MRI, with approximately 1/3 of the RNAV in the lung. c) 1D-RNAV

positions (red points) displayed at the host scanner screen that were used as

biofeedback and as surrogate signal.

Figure

2: a) Obtained respiratory navigator (1D-RNAV) positions were sent to a client

program, which displayed these positions with a guidance waveform on an in-room

monitor. Acquired 4D-MRI data were retrospectively sorted into respiratory-correlated

4D-MRIs using 1D-RNAV and 2D-RNAV surrogate signals. b) (Left) 1D-RNAV and 2D-RNAV

derived surrogate signals were compared by calculating the RMSE. (Right) The total

percentage and characterization of missing anatomical data in 4D-MRIs was quantified and

the largest cluster was identified.

Figure 3: Root mean square error (RMSE) between 1D-RNAV and

2D-RNAV surrogate signals for nine volunteers. The 4D-MRI numbers represent the

unguided (1), the natural guided (2), the guided with increased breathing

period (3), and long natural guided (4-39) 4D-MRI acquisitions.

Figure

4: 4D-MRI missing data percentage. The 4D-MRI numbers represent the unguided

(1), the natural guided (2), the guided with increased breathing period (3),

and long natural guided (4-39) 4D-MRI acquisitions. Per 4D-MRI, the missing

data percentage obtained with the 1D-RNAV and 2D-RNAV surrogate signal are

plotted, with a subdivision of multiple missing neighbors or maximum one

missing neighbor.

Table

1: This table summarizes the parameters used for

the SMS-4D-MRI sequence interleaved with the 1D respiratory navigator (1D-RNAV).

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0724