0705

Machine Learned Wave Encoded Neurovascular 4D Flow1Department of Medical Physics, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 2Department of Medicine, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States, 3Department of Radiology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Blood vessels, Velocity & Flow

Keywords: Wave Encoding, Trajectory Optimization, 4D Flow

Non-Cartesian sampling is often required for 4D Flow imaging because of more efficient sampling. Due to the heuristic nature of the optimization of such trajectories, we propose to parameterize and optimize wave encoded 3D Cartesian sampling using a gradient descent algorithm in a data-driven way. We demonstrate the feasibility of our framework in learning the sampling patterns and the wave parameters and providing high image quality for highly accelerated scans in digital phantoms, phantoms and in vivo with phase contrast.

Introduction

Efficient k-space sampling is essential for clinically feasible neurovascular 4D flow imaging given the inherently longer acquisition times required by multiple velocity encodings and high spatiotemporal resolution. Typically, Cartesian sampling with parallel imaging is thus often insufficient to achieve acceptable imaging times. 3D non-Cartesian sampling using heuristic1-3 and optimization-based4,5 sampling provides methods to achieve high acceleration without image quality degradation. However, non-Cartesian sampling comes with sensitivity to system imperfections and more challenging field-of-view tailoring. Recent work has suggested that machine-learned 2D sampling patterns6-8 can improve sampling performance, but have been restricted to anatomical imaging, 2D sampling, and straight Cartesian sampling. In this work, we aim to develop a methodology to optimize sampling for 4D flow MRI using parameterized readout trajectories while considering hardware limits. In particular, we investigate the Wave9 encoded 3D Cartesian sampling for which trajectory parameters (centers, radius, etc) are learned from a set of training data. This avoids time-consuming g-factor simulations and grid search10, optimizes the trajectory over a set of heterogeneous training cases and provides full flexibility to pursue non-CAIPI encoded imaging.Methods

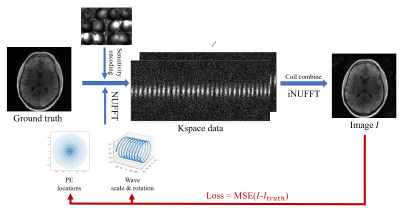

Trajectory Parameterization: The complete trajectory is constructed using a base trajectory designed using time-optimal methods11, that is repeated to construct a complete sampling pattern. Here, we explored the more trivial straight line trajectory and wave encoded sampling. For the straight line sampling, the k-space sampling centers are optimized while for wave encoding the center and local wave parameters are optimized on a per-readout basis.Optimization: The location of the phase encodes (PE) for both straight line readout and wave readout were initialized with a Poisson disc and the trajectory is optimized using a bank of training data, as illustrated in Figure 1. At each iteration, a case is selected from the training data and is sampled with the current 3D trajectory using differentiable non-uniform Fourier transform (NUFFT) and coil sensitivities. We subsequently estimate a reconstructed image using an adjoint NUFFT and calculate a mean squared error loss. The NUFFT was implemented by bindings to torchkbnufft12,13 and PyTorch14, which allowed for auto differentiation based gradient descent optimization of coordinate parameters. Hardware limits and resolution were maintained using hardtanh activation functions.

Optimization was based on 15 cases of L1-Wavelet reconstructed 3D radial 4D flow1, each with 5 velocity encodes and matrix size 256x256x256. Two cases were held out from training and used as test cases. Coil sensitivity maps were generated from low resolution images of the corresponding dataset and compressed to 12 channels using principal component analysis.

Image acquisition: Phantom scans were acquired with fast spoiled gradient echo (SPGR) sequences with straight line and wave readout, Poisson disc distributed PEs, and optimized PE locations for comparisons. The scan parameters are: receiver bandwidth(rBW)=125kHz, TE/TR=0.7/5.1ms. Representative volunteer scans were performed with 5-point velocity encoded phase contrast scans (venc=40.0 cm/s). The scan parameters are: rBW=62.5kHz, and TE/TR=2.9/7.8ms. The phantom and volunteer scans share scan parameters: number of phase encodes=5440, flip angle=8°, 0.86mm isotropic resolution, 256x256x256 image matrix size. Scans were conducted on the same 3.0 T scanner (GE Premier) and with the same coil (48ch head-coil) as used in the training data.

Results

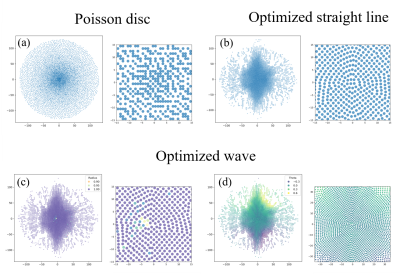

We optimized trajectories with straight line readout and wave readout (maximum radius=1, number of cycles=9) with 5440 PEs, which is approximately 9.5x accelerated. The sampling patterns after 1000 iterations are shown in Figure 2 (c-d). The radius of optimized wave were mostly approximately 1 except for the kspace center (Figure 2 (c) zoomed-in image) whereas the rotation angles show symmetric behavior. The centers are nearly fully sampled whereas the edges are vastly undersampled.Shown in Figure 3 are the PSF of the optimized patterns and the simulated reconstructed images. Images sampled with the wave trajectory show less aliasing artifacts and closest to ground truths.

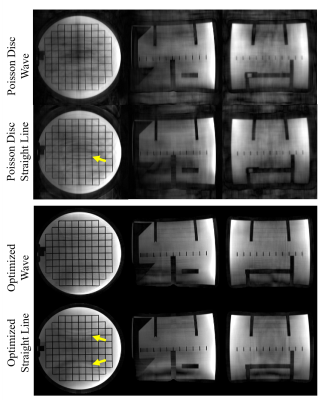

Figure 4 shows PILS reconstructed images scanned with straight line and wave readout, Poisson disc distributed PEs, and optimized PEs. Images acquired with optimized Wave readout show are with less aliasing artifacts and of higher image quality.

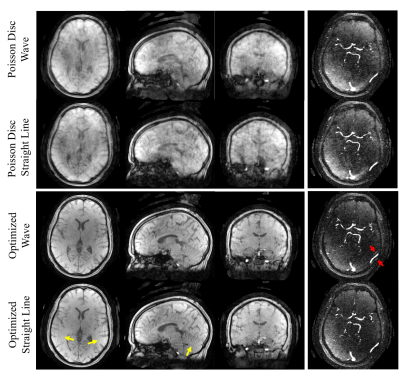

Shown in Figure 5 are the magnitude and angiogram images of the volunteer scan. There are more aliasing artifacts in the images acquired without wave, as the yellow arrows point out; however, the angiogram acquired with wave trajectory shows aliased vessels (red arrow), which may be attributed to gradient delays.

Discussion and conclusion

In this work, we successfully optimized parameterized trajectories with and without wave readout. By optimizing a 2D sampling pattern and trajectory parameters, we drastically reduced the search space and avoided unstable behaviors due to error accumulations in NUFFT and local minimum. During training images were much improved even without the help of iterative reconstruction. The phantom scans show agreement with the simulations in terms of image quality. We were able to apply the optimized sampling patterns with wave readout to phase contrast scans with ~3.5min scan time. Work is ongoing to evaluate the quantification accuracy of flow parameters, address gradient delays, and evaluate efficacy for deep learning image reconstruction.Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge research support from GE Healthcare, and funding support from the Alzheimer's Association (AARFD-20-678095) and from NIH grants R01AG075788, R21AG077337, R21NS125094, R01AG021155, P30AG062715, F31AG071183, UL1TR002373, and KL2TR002374.References

1. T. Gu et al., “PC VIPR: A High-Speed 3D Phase-Contrast Method for Flow Quantification and High-Resolution Angiography,” American Journal of Neuroradiology, vol. 26, no. 4, pp. 743–749, Apr. 2005.

2. K. M. Johnson, “Hybrid radial-cones trajectory for accelerated MRI,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 77, no. 3, pp. 1068–1081, 2017, doi: 10.1002/mrm.26188.

3. R. K. Robison, A. G. Anderson, and J. G. Pipe, “Three-dimensional ultrashort echo-time imaging using a FLORET trajectory,” Magn Reson Med, vol. 78, no. 3, pp. 1038–1049, Sep. 2017, doi: 10.1002/mrm.26500.

4. C. G. R, P. Weiss, G. Daval-Frérot, A. Massire, A. Vignaud, and P. Ciuciu, “Optimizing full 3D SPARKLING trajectories for high-resolution T2*-weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging,” arXiv:2108.02991 [cs], Aug. 2021, Accessed: Apr. 08, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2108.02991

5. G. Wang, T. Luo, J.-F. Nielsen, D. C. Noll, and J. A. Fessler, “B-spline Parameterized Joint Optimization of Reconstruction and K-space Trajectories (BJORK) for Accelerated 2D MRI,” arXiv:2101.11369 [eess], Nov. 2021, Accessed: Apr. 08, 2022. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/2101.11369

6. C. D. Bahadir, A. V. Dalca, and M. R. Sabuncu, “Learning-based Optimization of the Under-sampling Pattern in MRI,” arXiv:1901.01960 [cs, eess, stat], Apr. 2019, Accessed: Jan. 18, 2021. [Online]. Available: http://arxiv.org/abs/1901.01960

7. S. Seo, H. M. Luu, S. H. Choi, and S.-H. Park, “Simultaneously optimizing sampling pattern for joint acceleration of multi-contrast MRI using model-based deep learning,” Medical Physics, vol. 49, no. 9, pp. 5964–5980, 2022, doi: 10.1002/mp.15790.

8. M. V. W. Zibetti, G. T. Herman, and R. R. Regatte, “Fast data-driven learning of parallel MRI sampling patterns for large scale problems,” Sci Rep, vol. 11, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Sep. 2021, doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-97995-w.

9. B. B et al., “Wave-CAIPI for highly accelerated 3D imaging,” Magnetic resonance in medicine, vol. 73, no. 6, Jun. 2015, doi: 10.1002/mrm.25347.

10. D. Polak et al., “Highly-accelerated volumetric brain examination using optimized wave-CAIPI encoding,” J Magn Reson Imaging, vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 961–974, Sep. 2019, doi: 10.1002/jmri.26678.

11. M. Lustig, S.-J. Kim, and J. M. Pauly, “A Fast Method for Designing Time-Optimal Gradient Waveforms for Arbitrary k-Space Trajectories,” IEEE Trans Med Imaging, vol. 27, no. 6, pp. 866–873, Jun. 2008, doi: 10.1109/TMI.2008.922699.

12. M. J. Muckley, R. Stern, T. Murrell, and F. Knoll, “TorchKbNufft: A High-Level, Hardware-Agnostic Non-Uniform Fast Fourier Transform,” presented at the ISMRM Workshop on Data Sampling & Image Reconstruction, 2020.

13. A. Gossard, Bindings-NUFFT-pytorch. 2021. Accessed: Nov. 09, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://github.com/albangossard/Bindings-NUFFT-pytorch

14. A. Paszke et al., “PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library,” Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, vol. 32, pp. 8026–8037, 2019.

Figures