0678

Rapid 3D T1 Mapping Using Deep Learning-Assisted Look-Locker Inversion Recovery MRI1Biomedical Engineering and Imaging Institute and Department of Radiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, United States, 2Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering, NYU Tandon School of Engineering, New York, NY, United States, 3Department of Radiology and Biomedical Imaging, UCSF, San Francisco, CA, United States, 4Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Quantitative Imaging, Quantitative Imaging

Look-Locker inversion recovery (LLIR) imaging is an easy, accurate and reliable MRI method for T1 mapping. For 3D acquisition, LLIR imaging is usually performed with multiple repetitions, and additional idle time is placed between consecutive receptions. This idle time allows for signal recovery to improve SNR and ensures robustness to B1 inhomogeneity, but it also prolongs scan time. Simply eliminating the idle time reduces the accuracy of T1 quantification. In this work, a novel deep-learning approach was proposed to address this challenge, so that accurate 3D T1 maps can be generated from continuous 3D LLIR imaging without idle time.Introduction

Look-Locker inversion recovery (LLIR) imaging is an easy, accurate and reliable MRI method widely used for T1 mapping1–3. While 2D LLIR T1 mapping can be performed with single-shot imaging using only one inversion recovery (IR) preparation4, 3D LLIR T1 mapping typically requires multiple repetitions (one repetition following an IR preparation5. For 3D acquisition, additional idle time (referred to as time of delay, or TD for short) is generally placed between different repetitions, which not only allows for signal recovery to improve SNR, but also ensures sufficient robustness to B1 inhomogeneity when signal fully recovers back to the equilibrium state3, 6. However, the need for TD substantially reduces imaging efficiency and prolongs scan time. Simply eliminating the TD reduces the accuracy of T1 quantification unless additional flip angle information is available from additional B1 mapping. In this work, we proposed a novel deep-learning approach to address this challenge. We have shown that, with the help of deep learning, accurate 3D T1 maps can be obtained from a single continuous 3D LLIR acquisition without TD and without any additional information such as flip angle or B1 maps.Methods

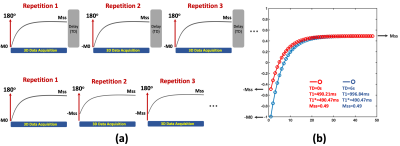

3D LLIR acquisition generally consists of multiple repetitions, and each of them starts with an IR preparation, as shown in Figure 1a. When the TD between consecutive repetitions is sufficiently long for complete signal recovery (e.g., back to equilibrium), the signal changes from -M0 to Mss in each repetition after the IR preparation, where Mss represents signal intensity at the steady state for gradient echo imaging. Synchronizing images from all repetitions results in a composite image series that can be used for quantification of apparent T1 (known as T1*) based on a three-parameter model3, and T1* can be converted to T1 using an analytic equation3. This acquisition scheme enables accurate and B1-insensitive T1 quantification at the cost of reduced imaging efficiency due to the need of TD. Without the TD, the signal does not return to equilibrium and it changes from -Mss to Mss from the second repetition. This still allows for estimation of T1* and Mss, but the lack of B0 information prevents conversion from T1* to T1, and T1 and T1* are the same in this case. Figure 1b demonstrates two simulated signal curves comparing T1 recovery with and without TD (blue and red curves, respectively), where the ground truth T1 was 1000ms. Without TD, T1* and Mss remain unaffected, while T1 becomes equivalent to T1*.A neural network was developed to estimate true T1 from biased T1 in 3D LLIR imaging without TD and it was tested for 3D brain T1 mapping using Golden-angle RAdial Sparse Parallel imaging (GRASP)-based T1 mapping (GraspT15). As shown in Figure 1b, the T1* estimated from GraspT1 with a TD of 6s (GraspT1-TD6) will be the same as both T1 and T1* estimated from GraspT1 without TD (GraspT1-TD0). As a result, it is possible to perform network training only using GraspT1-TD6 datasets for converting T1* to T1. After training, the network can then be applied to convert T1 estimated from GraspT1-TD0 (same as T1* from GraspT1-TD6) to true T1.

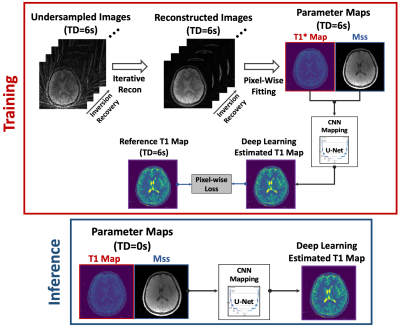

The overall training and inference pipelines are presented in Figure 2. The Mss map was also included to provide additional structure information. A pixel-wise loss function with L1 norm was enforced between the estimated T1 and the reference T1 maps. Relevant imaging parameters for GraspT1-TD6 acquisition included: stack-of-stars sampling, FOV=280x280mm2, matrix size=320x320, spatial resolution=0.875x0.875mm2, slice thickness=3mm, number of slices=32, TR/TE=3.67/1.74ms, flip angle=5o, total acquisition time= 169s.

The trained neural network was tested in 10 GraspT1-TD0 datasets, which were not included in the training and were acquired using the GraspT1-TD6 protocol without TD (scan time=76s). The trained neural network was applied to convert biased T1 to true T1 in GraspT1-TD0, and the estimated T1 maps were compared with reference T1 maps obtained from GraspT1-TD6.

Results

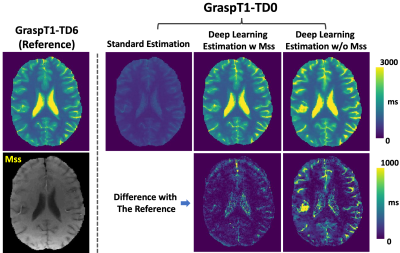

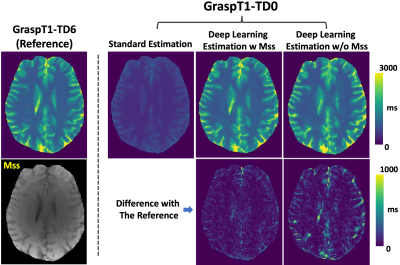

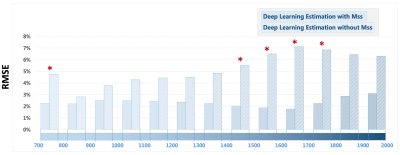

Figure 3 shows a representative case comparing a T1 map estimated from GraspT1-TD6 with T1 maps estimated from GraspT1-TD0. Eliminating the TD results in underestimation of T1 with standard estimation, while deep learning estimation was able to obtain accurate T1. Meanwhile, incorporation of the Mss map in network training helps improve the deep learning estimation. Figure 4 shows similar comparison in another subject, in which deep learning estimation also generated accurate T1 compared to the reference.Figure 5 summarizes the evaluation of deep learning T1 estimation in all the 10 cases based on RMSE. Image analyses were performed for different T1 ranges. Additional comparison was also performed between deep learning estimation with and without Mss. The results suggested that deep learning enables accurate T1 estimation in different T1 ranges without TD, and Mss can provide additional structure information that improves the estimation with statistical difference in five T1 ranges as highlighted by the red stars.

Conclusion

This work has demonstrated a novel use of deep learning for rapid continuous 3D LLIR T1 mapping with improved imaging efficiency. Deep learning enables accurate T1 quantification compared to the reference, and we have also shown that incorporation the Mss map with additional structure information in network training helps improve the performance of T1 estimation using deep learning.Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by the NIH grants R01EB030549, R21EB032917, R21EB031185, R01AR079442 and R01AR081344.References

1. Look DC, Locker DR: Time Saving in Measurement of NMR and EPR Relaxation Times. undefined 1970; 41:250–251.

2. Taylor AJ, Salerno M, Dharmakumar R, Jerosch-Herold M: T1 Mapping: Basic Techniques and Clinical Applications. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2016; 9:67–81.

3. Deichmann R, Haase A: Quantification of T1 values by SNAPSHOT-FLASH NMR imaging. J Magn Reson 1992; 96:608–612.

4. Wang X, Roeloffs V, Klosowski J, et al.: Model-based T 1 mapping with sparsity constraints using single-shot inversion-recovery radial FLASH. Magn Reson Med 2018; 79:730–740.

5. Feng L, Liu F, Soultanidis G, et al.: Magnetization-prepared GRASP MRI for rapid 3D T1 mapping and fat/water-separated T1 mapping. Magn Reson Med 2021; 86:97–114.

6. Li Z, Xu X, Yang Y, Feng L: Repeatability and robustness of MP-GRASP T1 mapping. Magn Reson Med 2022; 87:2271–2286.

Figures