0660

Association of thalamic neuroinflammation and the functional connectivity in a rat model of traumatic brain injury – a longitudinal study1A. I. Virtanen Institute for Molecular Sciences, University of Eastern Finland, Kuopio, Finland

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, fMRI (resting state), Light sedation

Post traumatic brain injury (TBI) neuroinflammation has been linked to many long-term outcomes of TBI. To better understand the interrelationship of the neuroinflammation and changes of functional connectivity, we followed rats after TBI in a series of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) experiments. We observed hypoconnectivity in the corticothalamic connections, which was laterally altered at the acute time point and correlated with the observed level of neuroinflammation in the lateroposterior thalamic nuclei. This sheds light on the potential role of focal post-traumatic neuroinflammation shaping large scale functional connectivity in the post-traumatic brain.Introduction

Neuroinflammation induced by traumatic brain injury (TBI) has been associated with many long-term outcomes of TBI, such as epilepsy1 and cognitive impairment2. While the initial injury disrupts the cortical areas, neuroinflammation is often observed in thalamic regions3. Moreover, the thalamus is closely interconnected with the cerebral cortex and other subcortical structures4,5, making it a vulnerable node of circuit dysfunction after TBI6. While both changes in the functional connectivity (FC) and the neuroinflammation of the thalamus after the injury have been widely studied, the combined effect of both is yet underexplored7. In this study, we wanted to gain a better understanding of the consequences of the TBI on corticothalamic FC and its interrelationship with thalamic inflammation. To achieve this, we have followed the rats after TBI in a series of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and positron emission tomography (PET) experiments.Methods

Traumatic brain injury was induced by lateral fluid-percussion injury (LFPI)8 in 19 animals and a control group of 6 animals was sham-operated. The rats were habituated and measured under a light 0.5% isoflurane sedation as described before9 at 10 days, 2 months, and 6 months after the induction of TBI. The baseline fMRI data were acquired 1 week before the injury. The daily habituation time was gradually increased and the overall habituation period was 3 days for the baseline and 2 days for the consequent measurements. The fMRI was measured with gradient-echo echo-planar imaging sequence (TR = 1 s, 17 slices) for 25 minutes (1500 repetitions). In addition to the traditional preprocessing pipeline (slice timing correction, motion correction, and registration to a reference brain), we implemented a motion scrubbing and Independent component analysis-based approach for motion removal, as described before9. The region of interest (ROIs) were drawn on the reference brain according to an anatomical atlas10. The ROIs included cingulate cortex (Cg), retrosplenial cortex (Rs), and lateroposterior thalamic nuclei ipsilateral (LPi) and contralateral (LPc) to the injury. The ROI selection was done based on PET to represent thalamic inflammation areas (LPi, LPc) and their cortical connections (Cg, Rs). The ROI analysis of FC was performed on motion-free parts of the signal as described previously9.The animals underwent PET imaging using a TSPO radioligand [18F]-FEPPA at 2 weeks post-injury induction. The ROIs were drawn in the myocardium and bilaterally in the lateroposterior thalamic nuclei. To remove the effect of the injected dose, the correlation of the uptake from the myocardium to the uptake of thalamic areas was modeled by fitting a linear model in the sham-operated animal, and then subtracting the uptake from the thalamic areas in all datasets. For correlation analysis between the uptake of the tracer and the FC, the effect of an injected dose was further removed.

Results

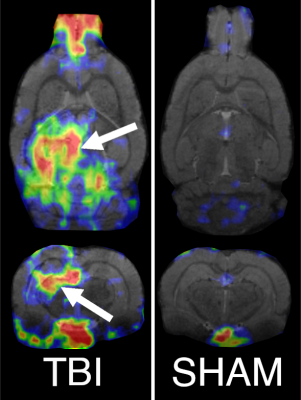

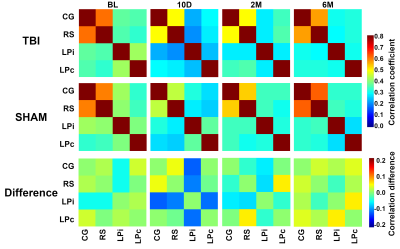

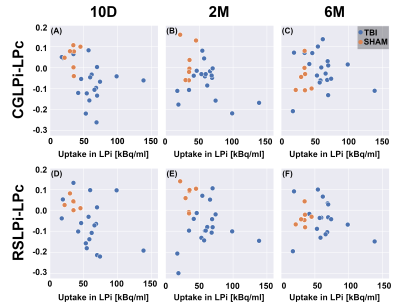

The PET data showed increased uptake of the TSPO-tracer in TBI animals in the perilesional thalamus, cortex, and hippocampus (Figure 1), which points to neuroinflammation in these areas. Specifically, in the thalamic area, we observed increased uptake in the lateroposterior and posterior thalamic nuclei. The sham-operated animals did not show any increased uptake of the tracer (Figure 1). The FC analysis of MRI data showed decreased connectivity in the TBI animals after the injury (Figure 2). The hypoconnectivity is mostly pronounced in the LPi at 10 days post-injury, while the connectivity of LPc decreased only slightly at this time point. Laterally altered connectivity of LP is still apparent at 2 months past the injury, while it diminishes by the 6 months time point (Figure 2). In the acute time point, we also detected decreased connectivity in the cortical connections in sham-operated animals, which is likely associated with the effect of craniectomy over the left parietal cortex. Additionally, the difference in the correlation values of the RS to the LPi and LPc in TBI animals correlated to the corrected FEPPA uptake in LPi in the acute time point (ρ = -0.5, p < 0.05). While the correlation was not significant at the chronic time points, the interrelation is still apparent in the 2 months post-injury (Figure 3).Discussion

Our study is one of the first longitudinal studies following the interrelationship of neuroinflammation and changes in functional connectivity after TBI in rats. Since the corticothalamic circuits are the focus of this study, the light sedation protocol in habituated rats was used to reduce the effect of anesthesia on these connections. For a better understanding of the large-scale circuits and networks, additional cortical areas should be included. However, since variable-size cortical lesions, craniectomy, and bleeds create artefacts on the fMRI images, more advanced preprocessing and ROI selection criteria are needed. Nevertheless, as in the LFPI animal model, thalamic neuroinflammation is commonly found in the lateroposterior thalamic nuclei, which is interconnected with the cingulate and retrosplenial cortex, which are not included in the primary lesion area, our analysis still provides a good insight into the post-TBI pathology.Conclusion

We have observed hypoconnectivity in the corticothalamic connections, which was laterally altered at the acute time point and correlated with the observed level of neuroinflammation in the LPi. This sheds light on the potential role of focal post-traumatic neuroinflammation in shaping large-scale functional connectivity in the post-traumatic brain.Acknowledgements

This project is co-funded by the Horizon 2020 Framework Programme of the European Union (Marie Skłodowska Curie grant agreement No 740264) and the Academy of Finland.References

1. Vezzani, A., French, J., Bartfai, T. & Baram, T. Z. The role of inflammation in epilepsy. Nat Rev Neurol 7, 31–40 (2011).

2. Donat, C. K., Scott, G., Gentleman, S. M. & Sastre, M. Microglial Activation in Traumatic Brain Injury. Front Aging Neurosci 9, 208 (2017).

3. Necula, D., Cho, F. S., He, A. & Paz, J. T. Secondary thalamic neuroinflammation after focal cortical stroke and traumatic injury mirrors corticothalamic functional connectivity. J Comp Neurol 530, 998–1019 (2022).

4. Fama, R. & Sullivan, E. v. Thalamic structures and associated cognitive functions: Relations with age and aging. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 54, 29 (2015).

5. Shepherd, G. M. G. & Yamawaki, N. Untangling the cortico-thalamo-cortical loop: cellular pieces of a knotty circuit puzzle. Nature Reviews Neuroscience 2021 22:7 22, 389–406 (2021).

6. Holden, S. S. et al. Complement factor C1q mediates sleep spindle loss and epileptic spikes after mild brain injury. Science 373, (2021).

7. Vinh To, X., Soni, N., Medeiros, R., Alateeq, K. & Nasrallah, F. A. Traumatic brain injury alterations in the functional connectome are associated with neuroinflammation but not tau in a P30IL tauopathy mouse model. Brain Res 1789, (2022).

8. Mishra, A. M., Bai, X., Sanganahalli, B. G., Waxman, S. G. & Shatillo, O. Decreased Resting Functional Connectivity after Traumatic Brain Injury in the Rat. PLoS One 9, 95280 (2014).

9. Dvořáková, L. et al. Light sedation with short habituation time for large-scale functional magnetic resonance imaging studies in rats. NMR Biomed e4679 (2021) doi:10.1002/NBM.4679.

10. Paxinos, G., Watson, C., Calabrese, E., Badea, A. & Johnson, G. A. MRI/DTI atlas of the rat brain.

Figures