0656

Systemic inflammation causes cerebral hypoperfusion, reductions in brain susceptibility and hippocampal hypoxia: a 9.4T MRI animal study1Department of Radiology, University of Calgary, Calgary, AB, Canada, 2School of Information Technology and Electrical Engineering, University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

Synopsis

Keywords: Multiple Sclerosis, Brain

Inflammation is a pathological characteristic of multiple sclerosis (MS). Individuals with MS are reported to experience reductions in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and brain hypoxia (low oxygenation). The cause of these phenomena is not well-known. We studied the possible association between inflammation and hypoxia in an inflammatory mouse model by quantifying CBF (arterial-spin labeling MRI) and magnetic susceptibility (quantitative susceptibility mapping), as well as measuring hippocampal oxygen using oxygen-sensitive probes. We found that inflammation is associated with reductions in CBF, brain susceptibility, and hippocampal oxygenation. This supports the idea that inflammation can induce brain hypoxia and disrupt cerebrovascular autoregulation.Introduction

Multiple sclerosis is an inflammatory disease of the central nervous system1. Recently, we discovered that brain hypoxia (low oxygenation) occurs in ~40% of individuals with MS2, and in an inflammatory animal model of MS3. Reductions in cerebral blood flow (CBF) have also been documented in MS4, 5, which could contribute to the development of brain hypoxia6. It is important to determine the underlying cause of hypoxia, whether it contributes to disease progression in MS and whether non-invasive MRI techniques can provide biomarkers to better understand hypoxia.This study aimed to determine if inflammation alone can cause hypoxia in a mouse model of inflammation induced by bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS). We quantified hypoxia with implanted oxygen-sensitive probes in one study, and in another performed arterial spin labeling (ASL) MRI, and quantitative susceptibility maps (QSM), to look for changes in CBF and deoxyhemoglobin in the brain (as a hypoxia marker) following LPS-induced inflammation. We compared whether CBF and susceptibility changes post-inflammation were related to brain oxygenation quantified using the implantable oxygen-sensitive probes. This research advances our understanding of whether inflammation can cause hypoxia and investigates whether ASL-MRI and QSM can be used to detect these pathologies.

Methods

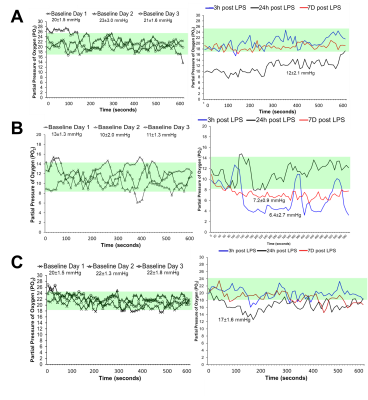

Female mice received saline (control) (n=20) or 2 mg/kg LPS (n=23) for inflammation via intraperitoneal injection once daily for 3 consecutive days. 9.4T MRI was performed three hours after the 3rd injection. CBF was quantified using continuous ASL (TR = 3000ms, TEeff = 13.5ms, averages: 16, RARE factor = 36, matrix =128x128, FOV = 25.6x25.6). T1 map: RARE-VTR sequence, TR=100, 500, 1000, 3000, 7500 ms, TE=10 ms). QSM maps were generated in a subset (saline n=7; LPS n=10) from 3D Multi-Gradient Echo images (TR = 100ms, TE = 3.1, echo spacing = 4 ms, matrix = 128x106x62, FOV = 19.2x15.9x9.3). MGE images were processed for QSM; ITK-SNAP software was used to extract the binary brain mask. Images acquired at five echoes underwent FSL PRELUDE unwrapping, as well as intermittent interval corrections between echoes of 2π jumps. A total field map was generated with a magnitude weighted least square fitting. The RESHARP ("Regularization Enabled Harmonic Artefact Reduction for Phase data") method was used to remove the background field using a 300µm-sized spherical kernel and the 5x10 Tikhonov regularization parameter. Dipole inversion was performed using the iLSQR method from the STI suite.We implanted three mice with partial pressure of oxygen (PO2) probes in the hippocampus. PO2 was recorded for 10-minutes for 3 baseline days pre-LPS, and at 3 hours, 24 hours, and 7 days post-LPS.

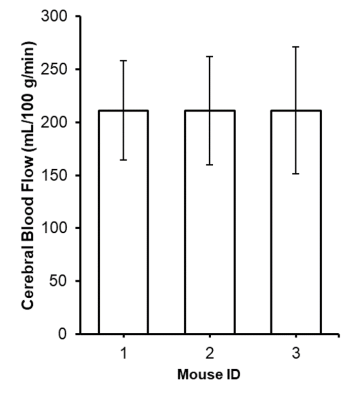

CBF and susceptibility were quantified in the cortex, hippocampus, and thalamus using in-house software. The threshold for hypoxia was defined as post-LPS PO2 two standard deviations less than the mean baseline PO2 for each mouse. We performed MRI to quantify CBF and obtain QSM maps 7 days post-LPS.

Results

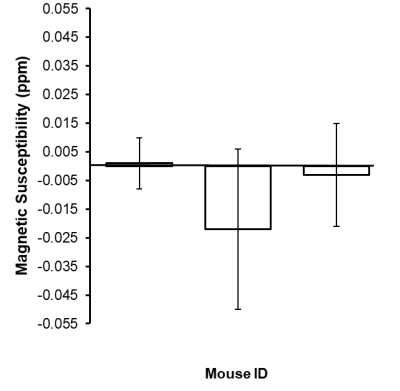

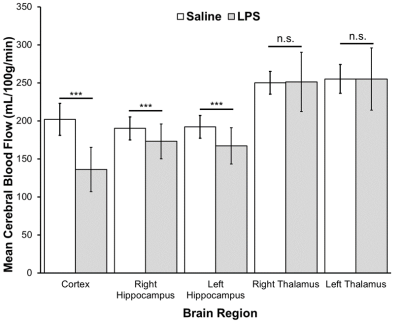

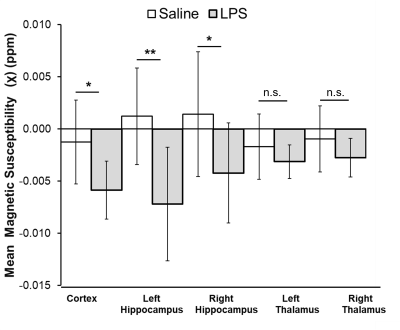

CBF was significantly reduced in the LPS group compared to controls in the cortex (p<0.0001), right hippocampus (p<0.01), and left hippocampus (p<0.001) (Fig.1). Magnetic susceptibility was significantly lower in the LPS group compared to controls in the cortex (p<0.05), left hippocampus (p<0.01), and right hippocampus (p<0.05) (Fig.2).The three mice with pO2 probes experienced hippocampal hypoxia. Mice 1 and 3 were hypoxic 24 hours post-LPS, while Mouse 2 was hypoxic 3 hours and 7 days post-LPS (Fig.3). Time series PO2 data (0.1 Hz) showed major changes in oscillation patterns post-inflammation for all mice (Fig.3). There were no differences in hippocampal CBF between mice 7 days post-LPS, and CBF values were similar to that of controls (Figs.1,4). Mouse 2, which was hypoxic at 7 days post-LPS, also had the lowest hippocampal susceptibility compared to the other two mice that did not experience hypoxia at that timepoint (Fig.5)

Discussion

We report significant reductions in CBF, brain susceptibility, and hippocampal PO2 following inflammation in the LPS model. This is strong evidence for the hypothesis that inflammation alone can cause brain hypoxia and major disruptions in cerebral vaso-regulation. The mechanism of inflammation-induced hypoxia is unknown, however, we propose that LPS elicits an inflammatory response which increases metabolic demands beyond oxygen supply and impairs cerebral autoregulation, thus causing hypoxia6.We also found that ASL-MRI and QSM are sensitive to these physiological changes as indicated by reduced CBF and susceptibility in the cortex and hippocampus 3 hours post-LPS (Fig.2). We also detected lower hippocampal susceptibility 7-days post-LPS in Mouse 3 (which was also hypoxic as measured by PO2 probes) as compared to the other two mice (Fig.5). The reduced susceptibility is opposite to what would be expected in a hypoxic condition, which indicates that multiple changes occurred in the brain post-LPS, making it likely that QSM can detect inflammation but the change it detects is not necessarily occurring as a result of hypoxia alone.

Acknowledgements

JD received funding from Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (RGPIN-2015-06517), Canadian Foundation for Innovation, and Brain Canada. QS received funding from the NSERC Canada Graduate Scholarships-Master’s program, Hotchkiss Brain Institute Recruitment Scholarship, and the Alberta MS Network. HS received funding from Australian Research Council (DE210101297).References

1. Haase S and Linker RA. Inflammation in multiple sclerosis. Therapeutic advances in neurological disorders. 2021; 14: 17562864211007687.

2. Yang R and Dunn JF. Reduced cortical microvascular oxygenation in multiple sclerosis: a blinded, case-controlled study using a novel quantitative near-infrared spectroscopy method. Scientific Reports. 2015; 5: 16477.

3. Johnson TW, Wu Y, Nathoo N, Rogers JA, Wee Yong V and Dunn JF. Gray Matter Hypoxia in the Brain of the Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Model of Multiple Sclerosis. PloS one. 2016; 11: e0167196.

4. de la Peña MJ, Peña IC, García PG, et al. Early perfusion changes in multiple sclerosis patients as assessed by MRI using arterial spin labeling. Acta radiologica open. 2019; 8: 2058460119894214.

5. Hostenbach S, Raeymaekers H, Van Schuerbeek P, et al. The Role of Cerebral Hypoperfusion in Multiple Sclerosis (ROCHIMS) Trial in Multiple Sclerosis: Insights From Negative Results. Frontiers in neurology. 2020; 11: 674.

6. Yang R and Dunn JF. Multiple sclerosis disease progression: Contributions from a hypoxia-inflammation cycle. Mult Scler. 2019; 25: 1715-8.

Figures

Figure 1. Cerebral blood flow (CBF) (mL/100g/min) (mean±SD) measured in the cortex, right and left hippocampus, and right and left thalamus of saline control (n=20) and LPS groups (n=23). CBF was measured with continuous arterial spin labeling (TR = 3000ms, TEeff = 13.5ms, averages: 16, RARE factor = 36, matrix =128x128, FOV = 25.6x25.6). T1 map: RARE-VTR sequence, TR=100, 500, 1000, 3000, 7500 ms, TE=10 ms). A Student’s t-test with a Bonferroni correction was used to compare between groups. *** = p≤ 0.001; n.s. = not significant

Figure 2. Magnetic susceptibility (mean±SD) measured in the cortex, right and left hippocampus, and right and left thalamus in saline control (n=7) and LPS groups (n=10). Susceptibility was calculated from brain quantitative susceptibility maps obtained from 3D Multi-Gradient Echo images (TR = 100ms, TE = 3.1, echo spacing = 4 ms, matrix = 128x106x62, FOV = 19.2x15.9x9.3). A Student’s t-test with a Bonferroni correction was used to compare between groups. ** = p≤ 0.01; * = p≤ 0.05; n.s. = not significant