0654

High Fat Diet Induced Cerebrovascular Pathology and Immune Cell Recruitment: A MRI Guided Histology Study1National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, United States, 2Magnetic Imaging Group, National Institute of Standards and Technology, Boulder, CO, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Neuroinflammation, Neuroinflammation

High fat diet (HFD) causes chronic low-grade inflammation and is associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular pathology and neurodegenerative disorders. Hypothalamus can sense peripheral signals and has been the major focus of HFD induced neuroinflammation. This work aims to study the activation of BBB endothelial cells, immune cell infiltration, and brain cell inflammation in the whole brain in real time caused by short-term HFD. Molecular MRI, using a new ultrahigh moment microfabricated gold-iron micro-disc, provides non-invasive guidance to the histology study. Our data indicate that HFD causes neuroinflammation in a remarkably short time in many structures of brain.INTRODUCTION

Chronic overnutrition, e.g. high-fat diet (HFD), causes low-grade inflammation and is associated with an increased risk of cerebrovascular diseases and neurodegenerative disorders. How this systemic consumption of HFD affects CNS inflammation is only partially known. As the interface between the CNS and peripheral immune system, BBB is critical during neuroinflammatory processes. In particular, endothelial cells are involved in the brain response to systemic stimulation by regulating the cellular movement of immune cells between the circulation and brain parenchyma. Endothelial cells of the CNS upregulate adhesion molecules, such as P-selectin, E-selectin, VCAM1, and ICAM1, during neurological disorders, either as a cause, or a consequence, of the disorder1. Our goal is to study the spatiotemporal activation of endothelial cells, immune cell recruitment and brain cell inflammation induced by HFD. Molecular MRI with a high moment microfabricated gold-iron micro-disc (Au-Fe Micro-Disc) was used to help guide histology to areas affected by HFD.METHODS

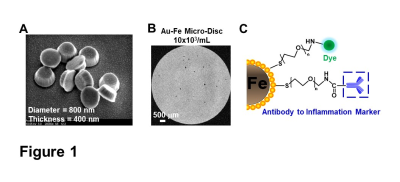

High fat diet. 6-week-old mice were fed with either standard chow diet (14% kcal from fat) or HFD (60% kcal from fat) for a duration of 6 weeks.Au-Fe Micro-Discs conjugation. Micro-Discs (diameter=800 nm, thickness=400 nm) was conjugated with antibodies via gold surface using modified EDAC-coupling reactions (Fig 1C).

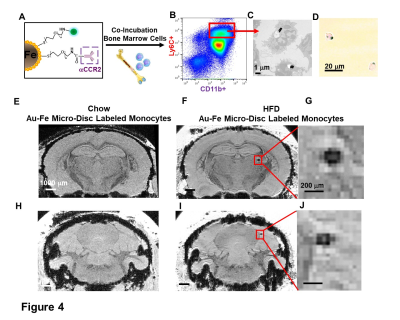

Monocytes labeling with Au-Fe Micro-Discs and Fluorescence-activated Cell Sorting (FACS). Bone marrow cells were isolated from HFD-mice and co-incubated with anti-CCR2-conjugated Micro-Discs at the ratio of 1:5 overnight. Labeled-CD11b+Ly6C+ monocytes were isolated by FACS (Fig 4A-B).

MRI study. Conjugated Discs (0.5x106/gram) or disc-labeled monocytes (12,500 cells/gram) were administered through tail vein. 24-hr post particle or cell infusion, MRI experiments were carried out on an 11.7-T animal scanner with a CryoProbe. T2*-weighted 3D gradient-recalled echo sequences were used for acquisitions. In-vivo imaging: isotropic resolution=75 µm, TE/TR=10/30 ms, FA=10°, NA=3. Ex-vivo imaging: isotropic resolution=50 µm, TE/TR=15/40 ms, FA=15°, NA=12.

Immunohistochemistry (IHC). Brain sections were stained using a standard procedure for free-floating immunohistochemistry.

RESULTS

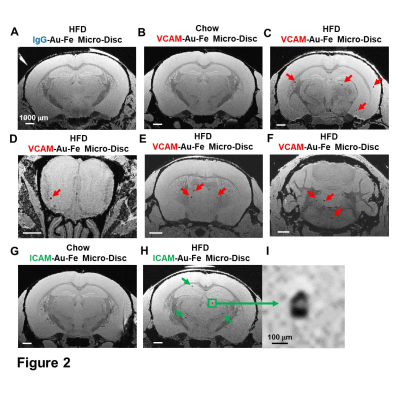

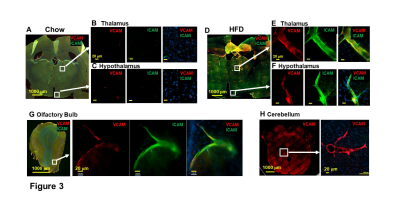

Micron sized iron oxide particles have been broadly used as MRI contrast agents for in-vivo cell tracking2, 3. While the MPIO particle has been used successfully, here we test a next generation microfabricated micron scale contrast agent, Au-Fe Micro-Disc, which has an higher magnetic moment due to the iron core and shows a stronger signal4 (Fig 1A,B). In addition, due to microfabrication each particle is very uniform unlike chemical preparations of iron oxide particles that can have large variability in iron content. Mice fed with 6-week HFD were infused with anti-VCAM1 or anti-ICAM1-conjugated Discs. After in-vivo MRI (24-hr post Disc infusion), mice were perfused for ex-vivo high-resolution MRI and histology. In-vivo and ex-vivo MRI corelated very well. Representative ex-vivo MRI were shown (Fig 2A-I). After perfusion washed out the Discs in circulation, hypointensities in the brain were likely caused by antibody-mediated binding of Micro-Discs to endothelial cells. Far fewer hypointense areas were detected in HFD-mice infused with rat-IgG-conjugated Discs (Fig 2A) or chow-diet-mice infused with anti-VCAM1-conjugated Discs (Fig 2B). Hypointensities were detected at many locations of HFD brain infused with anti-VCAM1-conjugated Discs. Thalamus, olfactory bulb, cerebellum, and cortex were constantly labeled (Fig 2C-F). Upon administration of anti-ICAM1-conjugated Discs, hypointensities were also detected at many brain structures of HFD-mice but not chow-diet-mice. A labeled area in thalamus is shown as an example (Fig 2G,H). Guided by MRI, we conducted IHC staining for VCAM1 and ICAM1 (Fig 3). IHC shows increased expression of VCAM1 and ICAM1 at the structures where hypointensities were detected (Fig 3 A-H), e.g., thalamus, olfactory bulb, cerebellum. Interestingly, no hypointensity was detected at hypothalamus for both anti-VCAM1 and anti-ICAM1-conjugated Discs (Fig 2C,H). In IHC, greater levels of VCAM1 and ICAM1 were observed at thalamus, than hypothalamus (Fig 3A-F).VCAM1 and ICAM1 are key mediators of leukocyte recruitment and disorder initiation. Thus, we studied the accumulation of CD11b+Ly6C+CCR2+ classical monocytes5 through MRI cell tracking (Fig 4). EM images and Prussian blue staining of labeled-monocytes were shown (Fig 4C,D). Accumulation of monocytes were detected at many locations of the HFD brain, e.g., olfactory bulb, thalamus and cerebellum, but not chow-diet-mice (Fig 4E-J). Notably, monocytes accumulation was not detected at hypothalamus (Fig 4F).

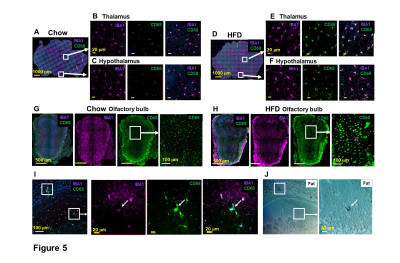

MRI also points to the locations of brain cell inflammation. Microglia activation, using IBA1 and CD68 as markers, was observed in many structures, e.g., thalamus and hypothalamus (Fig 5A-F), and olfactory bulb (Fig 5G-I). Fat staining was shown in activated microglia (Fig 5I-J). These results post the question: whether endothelia activation and immune cell migration are caused from peripheral or from activated microglia.

DISCUSSION

Antibody-mediated binding of microfabricated Au-Fe discs to target upregulated activated endothelial or tracking of labeled monocytes provided potent contrast effects that helped localize histology to areas not studied for short-term effects of HFD. Whether this approach will have the accuracy and specificity needed for in-vivo detection of regional vessel inflammation will be pursued.CONCLUSION

HFD causes neuroinflammation in a remarkably short time in mice. So far, most experiments have focused on the effects of HFD on hypothalamus. MRI guided histology show that HFD caused vessel inflammation, monocytes recruitment and microglia activation in many areas of the brain. Detailed timing and consequences of inflammation in these other areas of the brain will be the future focus.Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the intramural program at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS), National Institutes of Health (NIH).References

1. Gauberti M, Fournier AP, Docagne F, Vivien D, Martinez de Lizarrondo S. Molecular Magnetic Resonance Imaging of Endothelial Activation in the Central Nervous System. Theranostics. 2018;8(5):1195-212. Epub 2018/03/07. doi: 10.7150/thno.22662. PubMed PMID: 29507614; PMCID: PMC5835930.

2. Shapiro EM, Skrtic S, Sharer K, Hill JM, Dunbar CE, Koretsky AP. MRI detection of single particles for cellular imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(30):10901-6. Epub 2004/07/17. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403918101. PubMed PMID: 15256592; PMCID: PMC503717.

3. Pothayee N, Cummings DM, Schoenfeld TJ, Dodd S, Cameron HA, Belluscio L, Koretsky AP. Magnetic resonance imaging of odorant activity-dependent migration of neural precursor cells and olfactory bulb growth. Neuroimage. 2017;158:232-41. Epub 2017/07/04. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.06.060. PubMed PMID: 28669915; PMCID: PMC5614830.

4. Zabow G, Dodd S J, Shapiro E, Moreland J, Koretsky AP, Magn. Reson. Med., 2011; 65: 645–55. doi: 10.1002/mrm.22647. PMCID: PMC3065941.

5. Russo M, McGavern DB. Immune Surveillance of the CNS following Infection and Injury. Trends in Immunology. 2015; 36(10): 637-650. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2015.08.002. PubMed PMID: 26431941; PMCID: PMC4592776.

Figures