0644

A common brain network underlying successful neuromodulatory treatment of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder1University Health Network, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2Functional Neurosurgery Center, Shonan Fujisawa Tokushukai Hospital, Fujisawa, Japan, 3Neuroscience and Mental Health, Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute, Toronto, ON, Canada

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Psychiatric Disorders, Obsessive-compulsive disorder

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a debilitating condition, with up to 20% of patients being refractory to medical treatment. For these severe cases, neuromodulatory techniques targeting distinct brain areas have been successful. In this work, we used normative functional connectomics to identify the brain network underlying symptom improvement in OCD. A pan-modality efficacy map identified cortical and subcortical areas as key regions, and this specific network could be used to successfully predict clinical improvement. These results suggest that symptom reduction following neuromodulation involves the engagement of a common functional network that could be investigated as a biomarker of treatment success.Introduction

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a prevalent and debilitating condition that can engender severe dysfunction, with obsessions and compulsions occupying an average of ten hours per day in affected individuals [1]. OCD is also notoriously difficult to treat, with 40-60% of patients showing moderate response to conventional treatments (e.g. serotonin reuptake inhibitors and psychotherapy), and 10-20% with no response, being considered treatment-resistant [2], [3]. One longstanding approach to these severe cases is the direct modulation of brain circuits implicated in the condition’s pathophysiology, a form of intervention known as neuromodulation. OCD symptom reduction has been achieved by stimulation and lesioning of a variety of distinct brain areas [4]–[6]. These diverse target regions might be connected within a common brain network that subserves clinical response. It is therefore hypothesised that the connectivity of diverse targets to a common brain network is responsible for clinical outcomes, as has been shown previously for other psychiatric disorders [7]–[9]. Here, we harnessed normative functional connectomics to identify the brain network underlying symptom improvement in OCD.Methods

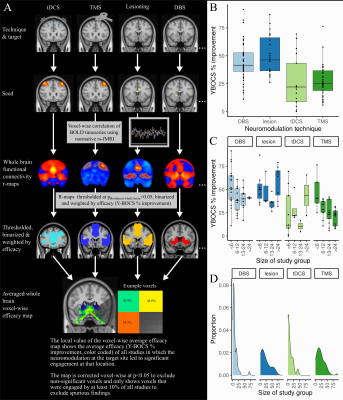

Relevant publications were identified by referencing three recent OCD neuromodulation meta-analyses [4]–[6] and by searching clinical trials registries (ClinicalTrials.gov, ICTRP). Studies were included if they i) assessed the efficacy of a neuromodulatory treatment for OCD, ii) reported on treatment efficacy in terms of percentage reduction from baseline on the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS), iii) involved more than one patient. Following data was extracted: target and coordinates, technique, sample size, and Y-BOCS improvement. 119 studies were included, reporting on, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS, n=42), transcranial direct current stimulation (tDCS, n=12), deep brain stimulation (DBS, n=42), lesioning (n=23). The major steps in our neuroimaging analysis are illustrated in Figure 1. Target coordinates in MNI space were extracted, spherical regions of interest were created using FMRIB Software Library tools, to approximate the extent of brain tissue either directly modulated by non-lesional stimulation techniques or directly ablated by lesioning techniques [8], [10]. Normative functional connectomics were used to estimate the effect of neuromodulatory interventions on distributed brain-wide networks [11]–[15]. The resulting r-maps were converted to t-maps, thresholded and binarized to permit a conservative analysis of spatial patterns of functional connectivity. Next, efficacy-weighted functional connectivity maps were created for each technique and overall. These captured brain-wide circuit engagement related to OCD symptom relief. To investigate potential similarities and differences between various neuromodulatory treatments for OCD, we calculated the voxel-wise spatial correlation between each pair of technique-specific efficacious maps. To assess the significance of these spatial correlations, permutation testing was performed. Each technique-specific efficacious map was re-computed 1000 times, with the improvement scores of each study being randomly assigned to a different study’s functional connectivity map, and the spatial correlation between pairs of permuted efficacious maps was calculated and compared to the true value. To assess whether functional network engagement of specific regions identified in the overall efficacy map might be predictive of clinical improvement at the study level we calculated the volume of overlap between each study’s map and voxels of the overall OCD efficacy map with i) ≥35% and ii) ≥50% Y-BOCS symptom improvement. An additive linear model was devised to predict study improvement from the overlap volume. All statistical analyses were performed using R (R 4.0.4., https://www.r-project.org) and RMINC (https://github.com/Mouse-Imaging-Centre/RMINC).Results

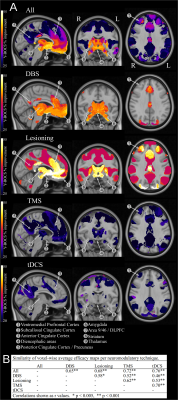

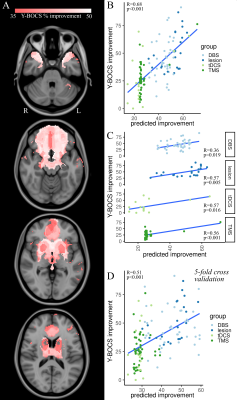

The average Y-BOCS improvement reported by the studies included in this analysis was 37.1% (range 4.70-91.50%) (Figure 1). Using normative functional connectivity mapping, a global, pan-modality neuromodulation efficacy map was derived that showed brain regions whose connectedness to target regions statistically relate to OCD improvement (Figure 2). Several different cortical and subcortical brain areas featured in this connectome were found consistently across the various efficacy maps included the ventromedial prefrontal/orbitofrontal cortex, subcallosal cingulate cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, medial parietal cortex, superior frontal gyri, and thalamic/striatal structures (Figure 2). Permutation testing revealed that each technique-specific map was significantly correlated to the others (p<0.005), attesting to both the cross-modality stability of the efficacious ‘network signature’ and its basis in the specific relationship between study clinical outcome and functional connectome (Figure 2). Finally, the OCD neuromodulation efficacy map and its predictive capability was confirmed using a linear model (Figure 3).Discussion

Employing a meta-analytic approach, this study identified the brain-wide network that might underlie efficacious neuromodulation for OCD across a variety of modalities and brain targets. Our analysis uncovered a distributed network of brain areas, comprising a variety of fronto-temporal cortical areas as well as amygdala, basal ganglia, and diencephalic structures, whose functional connectivity to the target correlated with outcome. This network proved robust across different modalities of neuromodulation and could be used to successfully predict the average clinical improvement at the study level.Conclusion

Taken together, these results suggest that reduction of OCD symptoms through stimulation or ablation of differing brain targets might involve the engagement of a common functional network – one that could potentially serve as a biomarker of treatment success.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Banting fellowship (#471913) to JG and a CIHR Postdoctoral Fellowship (#472484) to FVG. The Shireen and Edna Marcus Excellence Award has been made possible by Brain Canada Foundation and the Shireen and Edna Marcus Foundation and has been awarded to FVG.References

[1] A. M. Ruscio, D. J. Stein, W. T. Chiu, and R. C. Kessler, “The epidemiology of obsessive-compulsive disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication,” Mol. Psychiatry, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 53–63, Jan. 2010, doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.94.

[2] D. Denys, “Pharmacotherapy of obsessive-compulsive disorder and obsessive-compulsive spectrum disorders,” Psychiatr. Clin. North Am., vol. 29, no. 2, pp. 553–84, xi, Jun. 2006, doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2006.02.013.

[3] K. T. Eddy, L. Dutra, R. Bradley, and D. Westen, “A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy for obsessive-compulsive disorder,” Clin. Psychol. Rev., vol. 24, no. 8, pp. 1011–1030, Dec. 2004, doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2004.08.004.

[4] S. B. Hageman and G. van Rooijen, “Deep brain stimulation versus ablative surgery for treatment‐refractory obsessive‐compulsive disorder: A meta‐analysis,” Acta Psychiatrica, 2021, [Online]. Available: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/acps.13276?casa_token=3rNPnNb4WsEAAAAA:kX8Zvl1Hj3FyGSoNiteHXwUtqM8IpTzUakRVKwFhK-xKgPvChwz4KjiMH-W7LdsSvfWKgqFSyf2NLk0

[5] K. K. Kumar et al., “Comparative effectiveness of neuroablation and deep brain stimulation for treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: a meta-analytic study,” J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry, vol. 90, no. 4, pp. 469–473, Apr. 2019, doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2018-319318.

[6] N. Acevedo, P. Bosanac, T. Pikoos, S. Rossell, and D. Castle, “Therapeutic Neurostimulation in Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders: A Systematic Review,” Brain Sci, vol. 11, no. 7, Jul. 2021, doi: 10.3390/brainsci11070948.

[7] K. D. Ersche et al., “Brain networks underlying vulnerability and resilience to drug addiction,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 117, no. 26, pp. 15253–15261, Jun. 2020, doi: 10.1073/pnas.2002509117.

[8] M. D. Fox, R. L. Buckner, H. Liu, M. M. Chakravarty, A. M. Lozano, and A. Pascual-Leone, “Resting-state networks link invasive and noninvasive brain stimulation across diverse psychiatric and neurological diseases,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 111, no. 41, pp. E4367–75, Oct. 2014, doi: 10.1073/pnas.1405003111.

[9] B.-J. Li, K. Friston, M. Mody, H.-N. Wang, H.-B. Lu, and D.-W. Hu, “A brain network model for depression: From symptom understanding to disease intervention,” CNS Neurosci. Ther., vol. 24, no. 11, pp. 1004–1019, Nov. 2018, doi: 10.1111/cns.12998.

[10] B. T. Thomas Yeo et al., “The organization of the human cerebral cortex estimated by intrinsic functional connectivity,” J. Neurophysiol., vol. 106, no. 3, pp. 1125–1165, Sep. 2011, doi: 10.1152/jn.00338.2011.

[11] G. J. B. Elias et al., “Probabilistic Mapping of Deep Brain Stimulation: Insights from 15 Years of Therapy,” Ann. Neurol., Nov. 2020, doi: 10.1002/ana.25975.

[12] J. Germann et al., “Brain structures and networks responsible for stimulation-induced memory flashbacks during forniceal deep brain stimulation for Alzheimer’s disease,” Alzheimers. Dement., vol. 17, no. 5, pp. 777–787, May 2021, doi: 10.1002/alz.12238.

[13] G. J. B. Elias et al., “Mapping the network underpinnings of central poststroke pain and analgesic neuromodulation,” Pain, vol. 161, no. 12, pp. 2805–2819, Dec. 2020, doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001998.

[14] J. Germann et al., “Potential optimization of focused ultrasound capsulotomy for obsessive compulsive disorder,” Brain, Jun. 2021, doi: 10.1093/brain/awab232.

[15] K. Yamamoto et al., “Neuromodulation for Pain: A Comprehensive Survey and Systematic Review of Clinical Trials and Connectomic Analysis of Brain Targets,” Stereotact. Funct. Neurosurg., vol. 100, no. 1, pp. 14–25, 2022, doi: 10.1159/000517873.

Figures