0639

Distinct dACC Glutamate Modulation during Inhibitory Motor Control Driven by Negative Emotional Stimuli in Trauma-Exposed Youth using 1H fMRS1Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Psychiatric Disorders, Trauma, Adolescent Development

We investigated changes in glutamate in the dACC in children exposed to childhood trauma during motor control function with and without inhibition as well as with and without stimuli depicting negative affect using 1H fMRS. Independent of motor control with/without inhibition, trauma-exposed children exhibited a significant reduction in dACC glutamate when stimuli of negative affect were present, relative to stimuli without affect. These results provide greater insight on the neurochemistry supporting the influence of negative emotional context on motor control and highlight potential novel biomarkers for risk and resilience to posttraumatic stress.Introduction

Childhood trauma is one of the strongest risk factors for pediatric anxiety disorders 1. Trauma may contribute to hallmark symptoms of anxiety, such as excessive fear or worry, by heightening negative emotional responses, which in turn may overwhelm cognitive control ability 2,3. In healthy adolescents, fMRI has implicated the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) in facilitating task-related inhibitory control 4,5, and that dACC engagement is altered in trauma-exposed youth when inhibitory control is performed in the context of negative emotion 6–8. However, it remains unknown if atypical BOLD fMRI activation of the dACC in trauma-exposed youth is driven by altered excitatory or inhibitory neurotransmission. Both glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons are highly integrated within microcircuits resulting in a net synaptic balance between the excitatory and inhibitory (E/I) drive 9. This E/I balance can shift due to changes on the dynamics between the E/I neurotransmission during neural engagement related plasticity, which can be detected through task related changes in glutamate with ¹H fMRS 10. Therefore, in gaining a greater understanding of neural mechanisms driving altered dACC engagement in trauma-exposed youth, we utilized 1H fMRS to investigate dynamic changes in glutamate from the dACC during motor control in “Selective” (motor control + inhibition) vs “Non-Selective” (motor control) task modes. Additionally, to assess the impact of affect influencing inhibitory control, Selective and Non-Selective conditions were performed across two task conditions, with and without negative emotional stimuli [i.e., “Negative Affect Faces” vs “No Affect Squares”]. Independent of the Selective or Non-Selective mode, we hypothesized relatively less dACC glutamate during the Negative Affect Faces condition compared to the No Affect Squares condition suggesting inhibitory motor control function is impacted by negative emotional stimuli in trauma-exposed youth.Methods

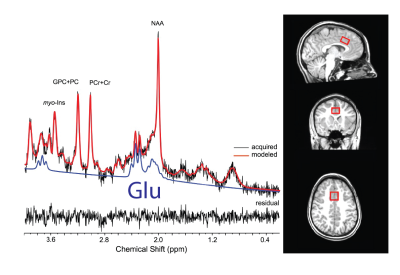

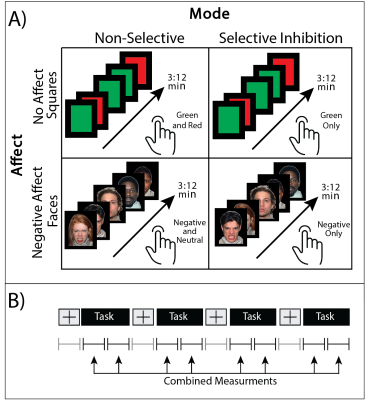

Data were collected from 17 trauma-exposed youth (58% female, age=11.8±0.8yrs, trauma=3±2events). Trauma was assessed using the Traumatic Events Screening Inventory, TESI [13] and defined as any DSM-5 criterion A trauma. The 1H fMRS was conducted on a Siemens 3T Verio system with a 32-channel volume head-coil. Utilizing MPRAGE T1-weighted images, a single-voxel (1.7x2.0x1.2cm3) was placed in the medial dACC utilizing the AVP approach 11 (Figure 1b). A visual-guided motor control task with distinct Non-Selective and Selective response modes were each executed with and without negative affect stimuli (neutral/negative emotional Faces vs red/green Squares) (Figure 2). During the Non-Selective mode, participants were presented with a flashing stimuli (50%/50% distribution, 100% responses) and were instructed to tap when presented with either stimuli; while during the Selective mode they were instructed to tap on the green/negative emotional face stimuli (80% distribution), but inhibit on the red/neutral face stimuli (20% distribution). The task was conducted as a separate 1H fMRS scans, with four 32s task epochs interspersed with 16s epochs (Figure 2b). A baseline control condition consisting of crosshair fixation preceded the task runs. Continuous 1H fMRS measurements were acquired with a temporal resolution of 16s throughout each task run using PRESS with OVS and VAPOR (TE=23ms, TR=4.0s, 13 measurements/task run, 4 averages/measurement, 2048 points, TA/task run=3:12min). The two 1H fMRS spectra in each task epoch were averaged after applying a phase and frequency shift correction followed by quantification using LCModel (Figure 1). A repeated measures generalized estimating equation (GEE) approach was used to model glutamate level with task condition (baseline condition, Non-Selective, Selective) as the main term for both task conditions with (Negative Affect Faces) and without (No Affect Squares) affect (SAS GENMOD; SAS Institute Inc). An additional GEE was conducted to assess the effect of glutamate across response mode (Non-Selective vs Selective) and affect (Squares vs Faces) and the interaction of the two terms.Results

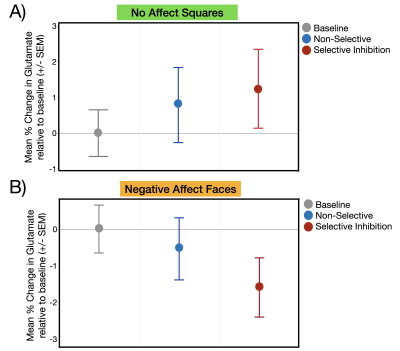

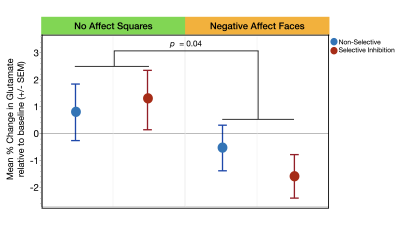

Glutamate levels were not significantly different across the three task conditions during the presentation of stimuli without affect (Squares: χ2= .65, p=0.72) or with affect (Faces: χ2= 1.07, p=0.30) (Figure 3a,b). The second set of analyses revealed a significant main effect of affect condition (χ2= 4.18, p=0.04) such that, independent of response mode, trauma-exposed youth demonstrated significantly less glutamate during the Negative Affect Faces condition compared to No Affect Squares condition (Figure 4). The response mode term (χ2= .02, p=0.90) and the interaction between response mode and affect (χ2= .54, p=0.46) were both non-significant (Figure 4)Discussion

We demonstrate for the first-time distinct task related changes in the dACC glutamate of trauma-exposed youth during inhibitory motor control that were driven by the influence of stimuli with negative affect – i.e., an effect where glutamate was significantly lower during the Negative Affect Faces condition compared to the No Affect Squares condition, independent of inhibitory motor controls (Selective or Non-Selective). This result potentially supports our framework that negative emotional processes may influence cognitive processes related to motor control in trauma-exposed youth. Further research is needed to investigate possible associations with motor control performance or with severity of trauma exposure, and whether glutamate changes driven by affect differ in youth without trauma-exposure.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the new investigator grant from the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Neurosciences, WSU, the Lycaki-Young Funds from the State of Michigan and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01-MH111682).

References

1. Green, J. G., McLaughlin, K. A., Berglund, P. A., Gruber, M. J., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Kessler, R. C. (2010). Childhood adversities and adult psychiatric disorders in the national comorbidity survey replication I: associations with first onset of DSM-IV disorders. Archives of general psychiatry, 67(2), 113-123.

2. Teicher, M. H., Andersen, S. L., Polcari, A., Anderson, C. M., Navalta, C. P., & Kim, D. M. (2003). The neurobiological consequences of early stress and childhood maltreatment. Neuroscience & biobehavioral reviews, 27(1-2), 33-44.

3. Pechtel, P., & Pizzagalli, D. A. (2011). Effects of early life stress on cognitive and affective function: an integrated review of human literature. Psychopharmacology, 214(1), 55-70.

4. Asemi, A., Ramaseshan, K., Burgess, A., Diwadkar, V. A., & Bressler, S. L. (2015). Dorsal anterior cingulate cortex modulates supplementary motor area in coordinated unimanual motor behavior. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 309.

5. Ordaz, S. J., Foran, W., Velanova, K., & Luna, B. (2013). Longitudinal growth curves of brain function underlying inhibitory control through adolescence. Journal of Neuroscience, 33(46), 18109-18124.

6. Mueller, S. C., Maheu, F. S., Dozier, M., Peloso, E., Mandell, D., Leibenluft, E., ... & Ernst, M. (2010). Early-life stress is associated with impairment in cognitive control in adolescence: an fMRI study. Neuropsychologia, 48(10), 3037-3044.

7. Carrion, V. G., Garrett, A., Menon, V., Weems, C. F., & Reiss, A. L. (2008). Posttraumatic stress symptoms and brain function during a response‐inhibition task: an fMRI study in youth. Depression and anxiety, 25(6), 514-526.

8. Tottenham, N., Hare, T. A., Millner, A., Gilhooly, T., Zevin, J. D., & Casey, B. J. (2011). Elevated amygdala response to faces following early deprivation. Developmental science, 14(2), 190-204.

9. Tatti, R., Haley, M. S., Swanson, O. K., Tselha, T., & Maffei, A. (2017). Neurophysiology and regulation of the balance between excitation and inhibition in neocortical circuits. Biological psychiatry, 81(10), 821-831.

10. Ferguson, B. R., & Gao, W. J. (2018). PV interneurons: critical regulators of E/I balance for prefrontal cortex-dependent behavior and psychiatric disorders. Frontiers in neural circuits, 12, 37.

11. Woodcock, E. A., Arshad, M., Khatib, D., & Stanley, J. A. (2018). Automated voxel placement: a Linux-based suite of tools for accurate and reliable single voxel coregistration. Journal of neuroimaging in psychiatry & neurology, 3(1), 1.

13. Ghosh-Ippen, C., F. J., R. Racusin, M. Acker, K. Bosquet, C. Rogers, C. Ellis, J. Schiffman, D. Ribbe, P. Cone, M. Lukovitz, and J. Edwards, Trauma Events Screening Inventory- Parent Report Revised, 2002, San Francisco, The Child Trauma Research Project of the Early Trauma Network and The National Centre for PTSD Dartmouth Child Trauma Research Group.

Figures