0623

Layer-resolved FMRI activation and connectivity of the left inferior frontal cortex during reading1Donders Institute, Radboud University, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 2Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, Nijmegen, Netherlands, 3Erwin L. Hahn Institute for Magnetic Resonance Imaging, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany, 4Faculty of Science and Technology, Magnetic Detection and Imaging, University Twente, Enschede, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, fMRI (task based), Laminar FMRI

We present results which demonstrate simultaneous bottom-up and top-down connectivity from BA44 to regions hierarchically inferior/superior to it in the context of a reading paradigm. BA44 is critical to a number of cognitive functions in humans, notably language. We also demonstrate that the layer dependent signal is sensitive to stimulus length. This effect is contrary to what would be expected in primary sensory cortices, as increased length relates to decreased input. Hence, we also provide insight to how canonical cortico-cortical circuits can lead to different outcomes depending on the nature of the input and the stage of the processing hierarchy.Introduction

Layer-resolved FMRI is becoming established as a feasible measure of bottom-up and top-down signal contributions to activation within brain regions. While the majority of the focus has been on sensory cortices, research is emerging which focuses on questions in cognitive neuroscience as this method transitions from proof-of-concept research to a new role as a methodological tool in application focused brain imaging (1,2,3,4,5,6).Although connectivity of cortical layers is a goal of the field, developments in this area have been limited (6,7,8,9,10).This abstract presents results which demonstrate simultaneous bottom-up and top-down connectivity from a portion of BA44 to regions hierarchically inferior and superior to it, in the context of a reading paradigm. BA44 is critical to a number of cognitive functions in humans, notably language(11)and speech-motor planning(12).We also demonstrate that the layer dependent signal is sensitive to stimulus length. This effect is contrary to what would be expected in primary sensory cortices, however, as increased length relates to decreased input. Hence, we also provide insight to how canonical cortico-cortical circuits can lead to different outcomes depending on the nature of the input and the stage of the processing hierarchy.Methods

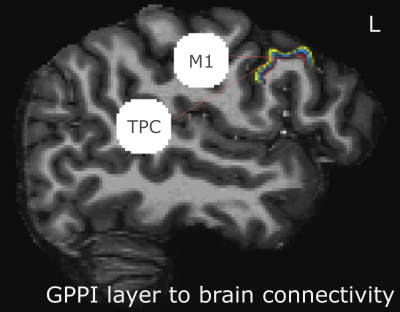

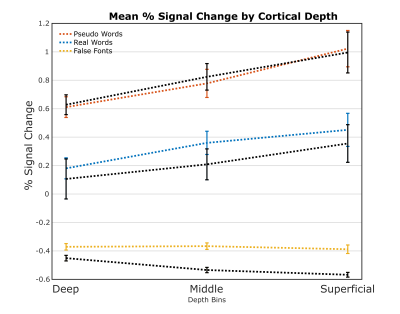

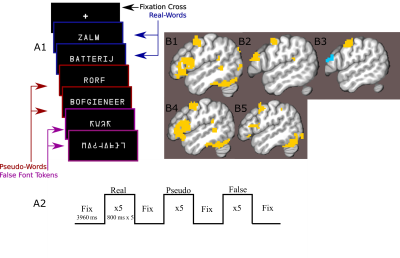

24 participants read long and short words, pseudo-words and false-font strings while lying in a an MRI scanner (Figure1a,b). Data were acquired on a Siemens Magnetom 7-tesla scanner(*1)with a 32-channel head coil(*2)at The Erwin L. Hahn Institute in Essen, Germany. During scanning, we acquired whole brain, submillimeter (0.943,0.900 slice-direction)resolution T2*-weighted GE-BOLD with a GRAPPA accelerated(8×1)3D-EPI acquisition protocol(13)with CAIPI shift kz=0,ky=4(14,15);effective TE=20ms,TR=44ms,effectiveTR=3960ms,BW=1044Hz/Px,FoV=215mm×215mm×215mm with 112 phase encode steps in the slice direction(100.8mm),α=13°,partial FF=6/8 in slice and phase-encoding directions. The first phase encoding gradient was applied in the P-A direction. Anatomical data for image registration, surface generation and layer definition were acquired with a distortion matchedT1-weighted inversion recovery EPI(IR-EPI)protocol based on the parameters of the functional acquisition. The following parameters were modified:α=90°,T1=800ms,TR=200ms,TE=20ms.Twelve 77 volume 3D-EPI data-sets were collected per subject, although some sessions were incomplete. No session contained fewer than 10 functional data-sets. MP2RAGE data-sets were also acquired for nonlaminar analysis(16).Stimulus items were presented in mini-blocks where each presented item within a mini-block was of the same condition type(Fig1a).Gray matter volumes were parcellated into three equivolume depth-bins following(17), containing the deep, middle and superficial layers (Fig2).Depth-dependent signal was extracted using a spatial GLM(18).Generalized psychophysiological interaction analysis(GPPI)was used to assess depth-dependent connectivity. GPPI is often performed on fMRI data to model the interaction between stimuli and brain regions(19).With depth-dependent data, it is possible to leverage knowledge of laminae to inform directed interpretations of task-dependent interaction between regions. Thus, GPPI on depth-dependent data can be regarded as a directed measure(6).Results

A nonlaminar effect of item length and of lexicality was observed in regions known to processes phonological information. A negative partial interaction between Length×Lexicality(real,pseudo) was observed in BA44d(Fig1B). Depth-dependent percent signal change(PSC)activation in BA44d was analyzed to determine PSC in each bin for all conditions. PSC was observed to increase as a function of cortical depth in both word and pseudo-word conditions, but the effect of word length appears to have been best localized to the middle bin(Fig3).The length responses in the middle bin differed by condition, with a larger effect for words than pseudo-words, and which resulted in a negative PSC for longer items. This length effect can be interpreted in terms of the increased ability to predict components of the longer real words, and thus to a reduced role of BA44d in word-processing and reduced lower-order input to the region. The connectivity results revealed that it was possible to relate the signal in the middle and superficial bins of BA44d to both lower and higher-order regions in the networks which process words and speech-motor planning. We demonstrate that, during pseudo-word reading, signal in the middle bin of BA44d predicted BOLD in a region of the temporo-parietal cortex(TPC)argued to interface between lower-order phonological processing regions and BA44d, which has been shown to support these computations via top-down signaling(11).The superficial bin instead predicted activation in orofacial motor cortex, which is related to speech-motor planning, covert articulation and building speech representations of the novel pseudo-words. Crucially, BA44d would be expected to act as an intermediate node in this network, receiving bottom-up input from TPC which could then be processed and propagated via efferent projections to sensorimotor cortexDiscussion

Using layer-specific task-based connectivity, we demonstrate simultaneous bottom-up and top-down connections from multiple regions to a single region as a function of reading. We furthermore identified a depth-dependent length effect which goes in the opposite direction of the lexicality effect. BA44 is known to contribute to articulatory speech motor planning, and to combining phonemes into words, and as such functions as an intermediate node in the articulation network and phonological processing network. Our results successfully mapped these lower and higher order connections through BA44d. Our finding that increased length related to decreased middle bin activation can be interpreted in light of BA44d being a non-sensory region. While increasing sensory input to lower-order cortices should result in increased activation, increased sensory input may also reduce processing demands throughout a brain network, resulting in reduced input to hierarchically superior regions.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Scheeringa R, Koopmans PJ, van Mourik T, Jensen O, Norris DG. The relationship between oscillatory EEG activity and the laminar-specific BOLD signal. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016 Jun 14;113(24):6761-6.

2. Lawrence, Samuel J.D. et al. 2018. “Laminar Organization of Working Memory Signals in Human Visual Cortex.” Current biology 28(21): 3435–40.

3. Lawrence, Samuel J.D., David G Norris, and Floris P. de Lange. 2019. “Dissociable Laminar Profiles of Concurrent Bottom-up and Top-down Modulation in the Human Visual Cortex.” Elife: 1–28.

4. Koizumi, Ai et al. 2019. “Threat Anticipation in Pulvinar and in Superficial Layers of Primary Visual Cortex (V1). Evidence from Layer-Specific Ultra-High Field 7T FMRI.” eNeuroeuro: ENEURO.0429-19.2019.

5. Finn, Emily S et al. 2019. “Layer-Dependent Activity in Human Prefrontal Cortex during Working Memory.” Nature Neuroscience: 22:(1687–1695).

6. Sharoh, Daniel et al. 2019. “Laminar Specific FMRI Reveals Directed Interactions in Distributed Networks During Language Processing.” PNAS: 1907858116.

7. Laurentius et al. 2017. “High-Resolution CBV-FMRI Allows Mapping of Laminar Activity and Connectivity of Cortical Input and Output in Human M1.” Neuron 96(6): 1253-1263.e7.

8. Huber L, Finn ES, Chai Y, et al. Layer-dependent functional connectivity methods. Prog Neurobiol. 2020

9. Chang, W., Langella, S., & Giovanello, K. (2022). Cross-layer Balance of Visuo-hippocampal Functional Connectivity Is Associated With Episodic Memory Recognition Accuracy. Research Square, 1–21.

10. Deshpande, G., Zhao, Robinson, J. (2022). Functional Parcellation of the Hippocampus based on its Layer-specific Connectivity with Default Mode and Dorsal Attention Networks. NeuroImage, 119078.

11. Hagoort P. Nodes and networks in the neural architecture for language: Broca's region and beyond. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2014 Oct;28:136-41. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2014.07.013. Epub 2014 Jul 23. PMID: 25062474.

12. Hickok G, Poeppel D. Dorsal and ventral streams: a framework for understanding aspects of the functional anatomy of language. Cognition. 2004 May-Jun;92(1-2):67-99. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2003.10.011. PMID: 15037127.

13. Poser BA, Koopmans PJ, Witzel T, Wald LL, Barth M (2010) Three dimensional echo-planar imaging at 7 tesla. Neuroimage51(1):261-6.

14. Breuer FA, et al. (2005) Controlled aliasing in parallel imaging results in higher acceleration (caipirinha) for multi-slice imaging. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine53(3):684-691.

15. Setsompop K, et al. (2012) Blipped-controlled aliasing in parallel imaging for simultaneous multislice echo planar imaging with reduced g-factor penalty. Magnetic Resonance in Medicine 67(5):1210-224

16. Marques JP, et al. (2010) Mp2rage, a self bias-field corrected sequence for improved segmentation and t1-mapping at high field. Neuroimage 49(2):1271-1281

17. Waehnert MD, Dinse J, Weiss M, Streicher MN, Waehnert P, Geyer S, Turner R, Bazin PL. Anatomically motivated modeling of cortical laminae. Neuroimage. 2014 Jun;93 Pt 2:210-20.

18. van Mourik T, van der Eerden JPJM, Bazin PL, Norris DG (2019) Laminar signal extraction over extended cortical areas by means of a spatial GLM. PLOS ONE 14(3): e0212493.

19. McLaren DG, Ries ML, Xu G, Johnson SC. A generalized form of context-dependent psychophysiological interactions (gPPI): a comparison to standard approaches. Neuroimage. 2012 Jul 16;61(4):1277-86.

*1. Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany

*2. Nova Medical, Wilmington, USA

Figures