0615

Layer dependent changes of neural activity underlying laminar fMRI

Daniel Zaldivar1, Yvette Bohraus2, Nikos Logothetis2,3,4, and Jozien Goense5,6,7

1LN, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, United States, 2Physiology of Cognitive Processes, Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics, Tuebingen, Germany, 3University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, 4International Center for Primate Brain Research, Shanghai, China, 5Department of Psychology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, United States, 6Department of Bioengineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States, 7Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, Urbana, IL, United States

1LN, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD, United States, 2Physiology of Cognitive Processes, Max Planck Institute for Biological Cybernetics, Tuebingen, Germany, 3University of Manchester, Manchester, United Kingdom, 4International Center for Primate Brain Research, Shanghai, China, 5Department of Psychology, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Champaign, IL, United States, 6Department of Bioengineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL, United States, 7Beckman Institute for Advanced Science and Technology, Urbana, IL, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Brain Connectivity, fMRI, Laminar fMRI and neurophysiology

How accurately fMRI reflects the underlying laminar differences in neural processing? In the current study we investigated the relationship between neural activity and fMRI signals across different cortical layers. We found layer and frequency dependent differences in neural activity during the presentation of visual stimulus that elicits positive and negative BOLD response.Laminar fMRI aims to study

how information is processed between and within different cortical layers and regions.

However, questions remain how accurately fMRI reflects the underlying laminar

differences in neural processing. We compared laminar fMRI and

electrophysiological responses to rotating checkerboard visual stimuli that

elicit PBR and NBR. We found that during PBR the overall correspondence between

the fMRI signals and local field potentials (LFP) was mostly confined within

the gamma frequency range with no particular dependence on one cortical layer

or fMRI modality. In contrast, for the NBR stimulus, the CBV showed good

correspondence with the LFP as both LFP-power and CBV increased in middle

layers while both signals decreased in superficial and deep layers.

Introduction

Functional MRI at the resolution of cortical layers (laminar fMRI) offers a novel window into activation patterns across the cortical sheet and allows us to ask fundamental questions about functional architecture, neurovascular coupling, and neuronal circuit dynamics. However, there are important outstanding questions about the correspondence between the fMRI signal and underlying neural activity at the laminar level. Here we investigated how changes in the laminar hemodynamic responses are linked to the underlying neurophysiological responses by comparing the depth dependent time courses of different fMRI- and neurophysiological signals.Methods

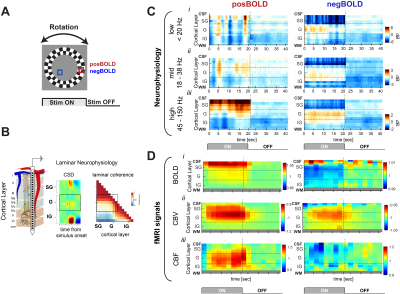

fMRI data were acquired at 4.7T (Bruker vertical scanner) and separate laminar electrophysiological experiments (probe of 16 linearly arranged contacts spaced 150 µm, NeuroNexus, Figure 1B) were performed on a total of twelve anesthetized monkeys. We presented visual stimuli in a block-design paradigm that elicits positive- (PBR) and negative BOLD responses (NBR; Figure 1A), and acquired BOLD, CBV, CBF and electrophysiological responses. We computed the relative power of the local field potentials (LFP; 0.5-150 Hz) across the different cortical layers (Figure 1B). The precise location of the laminar probe was determined based on current-source-density (CSD) analysis which is defined as the second spatial derivative of LFP signals (Figure 1B, left panel). The input layers can be identified as the location on the earliest current sink (white arrow). Boundaries between middle and deep layers were determined by computing the intercompartmental coherence at the gamma LFP range (right panel). Deep layers lack coherence with superficial and middle layers providing an additional marker for depthResults

Figure 1D shows the time courses from each fMRI signal across cortical depth in response to PBR and NBR stimuli. The time courses for the BOLD, CBF and CBV responses showed laminar differences, with earliest onset of CBF and CBV responses in granular layers. The neurophysiological response to the PBR indicates an increase in LFP power in superficial and middle layers across all frequency bands although the LFP power increase was found to be the largest at the gamma range. During the NBR stimuli the CBV response increased in middle layers which corresponded to an increase in the gamma power in the same cortical layer. This neurophysiological characteristic was also accompanied by a strong decrease in gamma power in superficial layers. A similar spatial distribution of LFP power across layers in response to the NBR stimulus was observed in other frequency bands. That is, a power increase in both low and mid frequency ranges was observed to be confined to middle layers while superficial layers strongly decreased. A post stimulus undershoot/overshoot was not much evident in our neurophysiology results, which leads us to suggest a hemodynamic origin of the different laminar fMRI post stimulus responses.Discussion

We show frequency and layer dependent differences in neural activity during the PBR and NBR conditions. During the PBR there was no obvious (one-to-one) relationship between the power of LFP bands and the amplitude of the fMRI signals across layers, although all layers showed signal increases (both fMRI and neurophysiology). Such a relationship was more evident during the NBR where we found the profile of neural activity to correlate with the CBV profile. This suggests that despite visual information reaching the main thalamic recipient layer (middle layer) during NBR, this does not elicit an increased response in the other layers, although the changes in neural activity do trigger an increase in CBV. This may be due, partly, to the strong inhibitory control elicited by feedback inputs targeting superficial and deep layers. The decrease in LFP power seen in deep and superficial layers during the NBR resembles that seen under top-down modulation of V1 activity and this may represent feedback processing3. This is supported by anatomical studies showing feedback projections preferentially target superficial and deep layers, while avoiding middle layers4,5.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Goense et al., Neuron 76:629-639 (2012); 2. Shmuel et al., Nat. Neurosci 9:569-577 (2006); 3. Van Kerkoerle et al., Nat Commun 8, 13804 (2017); 4. Markov et al., J Comp Neurol 522, 225-259 (2014); 5. Henry, et al., Eur J Neurosci 3, 186-200 (1991).Figures

(A) Stimulus used to investigate the

neurophysiological response of cortical layers to stimuli that elicit positive

BOLD response (red) and negative BOLD responses (blue).

(B) Representation of V1 layers: supragranular (SG;

superficial), granular (G, middle) and infragranular (IG, deep) layers. Average evoked CSD analysis use for electrode alignment. (C) layer dependent temporal dynamics of

neurophysiological activity in response to PBR and NBR stimuli in different LFP bands. (D) layer dependent temporal dynamics three fMRI signals. (i) BOLD; (ii) CBV; and (iii) CBF.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0615