0612

MR thermometry of RF heating in the human brain at 7T using the harmonical initialized multi-echo model with SVD-based motion correction1Center for Image Sciences - Computational Imaging Group, UMC Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands, 2Biomedical Engineering - Medical Imaging Analysis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, Netherlands

Synopsis

Keywords: Safety, Safety

A multi-echo signal model was presented to measure RF-induced temperature rise in the brain at 7T. The proposed method corrects drift fields based on near-harmonic 2D reconstruction and is complemented by an SVD-based motion-correction scheme. The method was tested in 2 volunteers, showing a maximum temperature increase of 0.25 °C with a precision of 0.12 °C. The reliability of the results was strengthened by measurements in which a heating pad was placed on the forehead of one volunteer. This measurement and thermal simulations indicated that the heatpad induced considerably more heating in the brain (3.5 °C) than SAR-constrained RF exposure.

Introduction

RF safety assessment is a major prerequisite for MRI, as unconstrained RF exposure can result in excessive heating and possibly tissue damage.1,2 Especially for the head, constraints (expressed in specific absorption rate, SAR) are more stringent.3 Previous thermal studies predicted a peak temperature rise of 0.5 °C for head coils in the brain when operating at maximal SAR.4 Validation of these thermal simulations of RF exposure, however, is challenging. Most attractive is validation using MR Thermometry (MRT) using the proton resonance frequency shift method. A model-based multi-echo MRT approach, using fat-referenced near-harmonic 2D reconstruction for drift estimation, has previously been proposed for sub-degree temperature rise measurements in the human thigh.5 Extension to the human brain, however, requires motion correction as the large degree of rotational freedom and presence of paranasal sinuses introduce susceptibility artifacts.6–9 The aim of this study is to evaluate if any temperature rise during MRI RF exposure can be observed in the human brain. For this purpose, the previously proposed method was extended with a motion-correction scheme, using three orthogonal slices to determine motion parameters.Methods

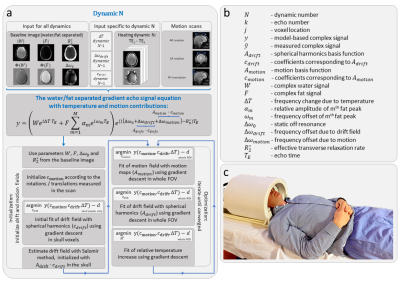

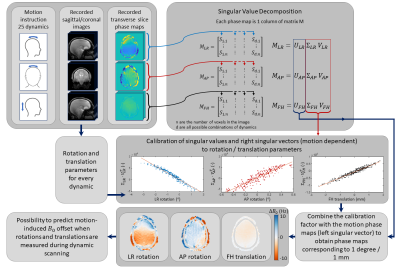

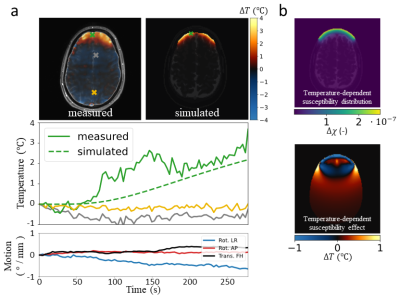

The harmonic initialized multi-echo model-based (HIMM) MRT method5 combines the model-based multi-echo water/fat separated approach as presented by Poorman et al.10 with the near-harmonic 2D reconstruction method as presented by Salomir et al.11 For our purpose, we added a term for motion-induced susceptibility changes (Δωmotion) to the model (figure 1a). The dynamic change in phase as a result of motion is modeled as the product of the basis of motion fields (Amotion, measured in a pre-scan), which includes a motion-induced field vector for rotations around the left/right (LR) and anterior/posterior (AP) axes, as well as feet/head (FH) translations, with the coefficient vector cmotion (initialized using motion parameters). The motion-correction scheme (figure 2) was implemented using motion-calibration scans and Singular Value Decomposition (SVD). To test the motion-correction model, MRT measurements were performed on the brain with and without RF heating. Additional measurements were performed with a hot tapwater-heated heatpad on the forehead to evaluate if any heating can be observed.Acquisition

MR scans were performed on a 7T system (Achieva, Philips Healthcare, Best, NL). Brain imaging was performed in 2 subjects (2 male, age 23-43) using the Nova 8Tx-32Rx head coil (Nova Medical, Wilmington, MA, USA) (figure 1c). For temperature measurements, spoiled 18-echo gradient echo MRT scans (TE1=1.2 ms, TEspacing=1.2 ms, TR 30 ms, 5x5x8 mm3 resolution, 220x200x8 mm3 FOV, flip angle 11°, single-shot, cardiac triggered,12 scan duration 429-538 seconds) were acquired for 3 orthogonal slices. We acquired a baseline scan without heating, a heating scan,9 and motion-calibration scans in which volunteers were asked to deliberately move their head (first LR-rotation, then AP-rotation, then FH-translation, 25 dynamics each). Due to space limitations with the Nova coil, the measurement with the heatpad was performed with an in-house built 8TxRx head coil.

Due to the high transverse relaxation rate of bone, only the echoes <10 ms were used for fitting of the drift field. Motion-corrected skull regions were furthermore temporally averaged (sliding window of 3 dynamics) to make the drift field estimation more robust to noise.

Results

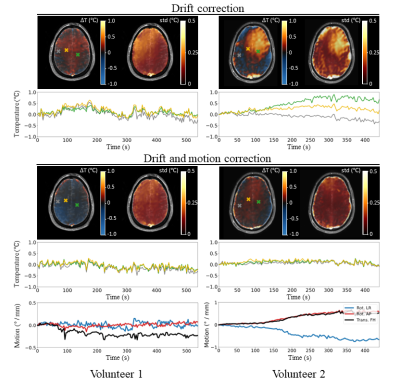

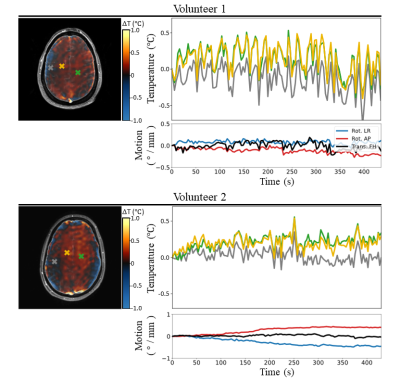

The motion correction scheme allowed reducing the temporal standard deviation in the brain by 43% (figure 3). The low SAR scan without motion correction returned a temperature evolution which closely corresponded to motion patterns (temporal standard deviation of 0.17 °C). Using motion correction, most of these motion-induced temperature fluctuations are corrected for (temporal standard deviation of 0.12 °C). Dynamic MRT imaging with maximum allowed RF heating resulted in heating hotspots predominantly in the inner brain, with temperature elevations up to 0.25 °C (figure 4). These individual results are in agreement to a previous study where a temperature rise of 0.20 °C was observed, averaged over 8 subjects.7 As the RF-induced temperature increase was identified to be very low, it was attempted to induce temperature increase in the brain using a heatpad (figure 5). The frontal side of the brain now shows considerable temperature increase (up to 3.5 °C), which was confirmed by thermal simulations (Sim4Life, ZMT, Zurich). Due to susceptibility effects in the fat signal from the skull,13 the frontal part of the skull was excluded in drift field corrections for the heatpad measurement.Discussion and conclusion

We have complemented a previously proposed model-based MRT method5,10,11 with an SVD-based motion-correction scheme to measure RF-induced heating in a human brain. Without motion correction, the drift field correction using the skull already corrects for a large part of the motion disturbances. However, spatial patterns of motion disturbances are different from drift fields. The addition of a motion term in the model therefore improved the accuracy. Using this method, temperature increases up to 0.25 °C were observed in the evaluated slices. Temperature rise is more clearly identified in volunteer 2 with a more inferior slice position, which is also where the SAR hotspot is expected.14 This RF-induced temperature increase is negligible compared to heating induced by a heatpad, which showed a clear temperature rise in the frontal part of the brain (up to 3.5 °C). This work provides additional indications that temperature increase in the brain while abiding local SAR limits is very modest.Acknowledgements

No acknowledgement found.References

1. Schaefer DJ, Shellock FG. Health effects and safety of radiofrequency power deposition associated with magnetic resonance procedures. In: Magnetic Resonance Procedures: Health Effects and Safety. ; 2001:55-74.

2. Marshall J, Martin T, Downie J, Malisza K. A comprehensive analysis of MRI research risks: In support of full disclosure. Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences. 2007;34(1):11-17. doi:10.1017/S0317167100005734

3. IEC. Medical Electrical Equipment. Part 2-33: Particular Requirements for the Safety of Magnetic Resonance Equipment for Medical Diagnosis. IEC 60601-2-33.; 2015.

4. Mao W, Wang Z, Smith MB, Collins CM. Calculation of SAR for transmit coil arrays. Concepts Magn Reson Part B Magn Reson Eng. 2007;31(2):127-131. doi:10.1002/cmr.b.20085

5. Kikken MWI, Steensma BR, van den Berg CAT, Raaijmakers AJE. Multi-echo MR Thermometry in the upper leg at 7T using near-harmonic 2D reconstruction for initialization. Magn Reson Med. Submitted.

6. Liu J, de Zwart JA, van Gelderen P, Murphy-Boesch J, Duyn JH. Effect of head motion on MRI B0 field distribution. Magn Reson Med. 2018;80(6):2538-2548. doi:10.1002/mrm.27339

7. le Ster C, Mauconduit F, Mirkes C, Vignaud A, Boulant N. Measuring radiofrequency field-induced temperature variations in brain MRI exams with motion compensated MR thermometry and field monitoring. Magn Reson Med. 2022;87(3):1390-1400. doi:10.1002/mrm.29058

8. le Ster C, Mauconduit F, Mirkes C, et al. RF heating measurement using MR thermometry and field monitoring: Methodological considerations and first in vivo results. Magn Reson Med. 2021;85(3):1282-1293. doi:10.1002/mrm.28501

9. Kikken MWI, Steensma BR, van den Berg CAT, Raaijmakers AJE. MR thermometry in the brain at 7T using a multi-echo water-fat separation model: Motion-induced field disturbance. ISMRM High Field Workshop. Lisbon, 2022.

10. Poorman ME, Braškutė I, Bartels LW, Grissom WA. Multi‐echo MR thermometry using iterative separation of baseline water and fat images. Magn Reson Med. 2019;81(4):2385-2398. doi:10.1002/mrm.27567

11. Salomir R, Viallon M, Kickhefel A, et al. Reference-free PRFS MR-thermometry using near-harmonic 2-D reconstruction of the background phase. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2012;31(2):287-301. doi:10.1109/TMI.2011.2168421

12. Steensma BR, van den Berg CAT, Raaijmakers AJE. Towards high precision thermal based RF safety assessment with cardiac triggered MR thermometry. Proceedings of the 2021 ISMRM & SMRT Annual Meeting and Exhibition; 1260.

13. Sprinkhuizen SM, Konings MK, van der Bom MJ, Viergever MA, Bakker CJG, Bartels LW. Temperature-induced tissue susceptibility changes lead to significant temperature errors in PRFS-based MR thermometry during thermal interventions. Magn Reson Med. 2010;64(5):1360-1372. doi:10.1002/mrm.22531

14. van Lier ALHMW, Kotte ANTJ, Raaymakers BW, Lagendijk JJW, van den Berg CAT. Radiofrequency heating induced by 7T head MRI: Thermal assessment using discrete vasculature or Pennes’ bioheat equation. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 2012;35(4):795-803. doi:10.1002/jmri.22878

Figures