0606

Temperature Prediction for Bilateral Deep Brain Stimulation Electrodes Undergoing MRI

Nur Izzati Huda Zulkarnain1, Alireza Sadeghi-Tarakameh1, Jeromy Thotland1, Noam Harel1, and Yigitcan Eryaman1

1Center for Magnetic Resonance Research (CMRR), University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

1Center for Magnetic Resonance Research (CMRR), University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN, United States

Synopsis

Keywords: Safety, Neuro

We utilized a previously proposed workflow to predict heating around the contacts of bilateral deep brain stimulation (DBS) electrodes undergoing MRI. Phantom experiments demonstrated a quantitative agreement with the simulated and experimentally measured temperature for different electrode trajectories and excitations.Introduction

Patients implanted with DBS face tissue heating risk during MRI scans1. This heating is caused by the time-varying electromagnetic (EM) excitation which induces current along the DBS shaft, resulting in excessive power dissipation in the surrounding tissue at the contact points2-3. Previously, we proposed a temperature prediction workflow to assess the RF heating risk before an MRI scan4. It consists of a simple quasi-static EM model, thermal simulations, and MR-based current measurement5. In this workflow, an equivalent transimpedance is defined as the ratio of the electrode contact voltage, Vc, and the current induced in the electrode shaft, Is, during the calibration phase. This workflow was validated for electrodes with different trajectories, terminations, power levels, and excitation types for a unilateral DBS electrode in a box phantom. In this work, we investigated the accuracy of the workflow in a more realistic setting: bilateral DBS in a head-shaped phantom for multiple excitation patterns and trajectories.Method

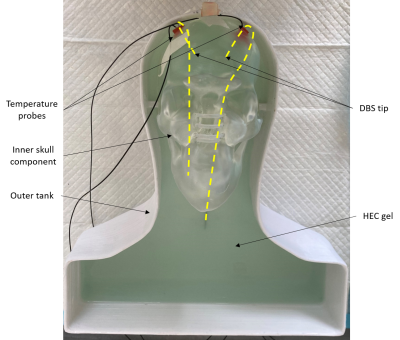

All experiments were conducted in a 3T scanner (MAGNETOM Prisma, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) using the dual-drive body coil as the transmitter and a 20-channel head/neck coil (Head/Neck 20, Siemens Healthineers, Erlangen, Germany) as the receiver. Two DBS electrodes (directional lead, Infinity DBS system, Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) were placed into a human head-shaped phantom shown in Figure 1, consisting of an outer tank and a nested skull6. This phantom allowed us to fix the distal end of the DBS electrode while changing the trajectory of the extra-cranial portion of the electrode. The tank and the skull were filled with a uniform, tissue-mimicking gel mixture of hydroxyethyl cellulose (14g/L), NaCl (2.25 g/L), and CuSO4 (0.25 g/L). The resulting conductivity and permittivity are 0.45 S/m and 79 respectively, and specific heat capacity and thermal conductivity are 4.2 MJ/m3-K and 0.58 W/mK respectively.We used turbo spin echo (TSE) pulse sequences (FA = 150°, TA = 189 s, echo train length = 15) to induce heating at the contacts and measured the temperature in real time using temperature probes (Lumasense Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) attached 3.3 mm and 2.1 mm away from the most distal contact point of electrodes 1 and 2 respectively. The heating experiments were performed with quadrature excitation for three different trajectories. The DBS electrodes were positioned contralateral and ipsilateral in Trajectories 1 and 2 respectively. In Trajectory 3, an extra-cranial loop was formed on each DBS electrode. The heating experiments for Trajectory 1 were also repeated for three different linear excitations. Additionally, we experimentally determined an implant-friendly mode for Trajectory 2 by optimizing the contribution from each transmit channel such that the maximum value of induced current on two electrodes is minimized simultaneously.

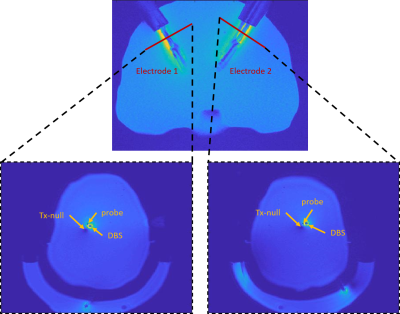

Is was estimated using an MR-based measurement. First, we acquired a 3D-GRE image (TR/TE = 20/2.64ms, in-plane resolution = 0.5 mm, slice thickness = 3mm) at a plane perpendicular to the electrode shaft approximately 30 mm away from the DBS tip and measured the distance between DBS electrode and Tx-null. Figure 2 shows the orientation of the DBS electrodes in the skull, the planes used in the current measurement, and the 3D-GRE images used to calculate the induced currents in both electrodes. Next, we acquired a low-power pre-saturated turbo-flash B1 map sequence (TR/TE = 10000 ms/2.24 ms, nFA = 80°, readout FA = 5°) at a plane underneath the electrode tip and measured the mean value of the incident B1+ of the transmit coil. We calculated Vc by utilizing the transimpedance value of 88 Ω we previously determined in our unilateral validations. The Vc was then imposed as the boundary condition in the quasi-static EM simulation model in Sim4life (Zurich Medtech, Zurich, Switzerland). The resulting SAR distribution was used to solve the bioheat equation in the transient thermal simulation. The simulated and the measured heating curves were compared and quantified using root-mean-squared error (RMSE).

Results

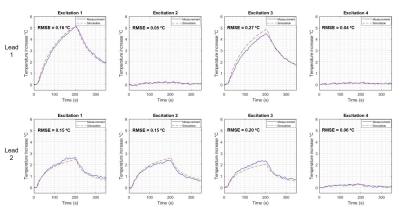

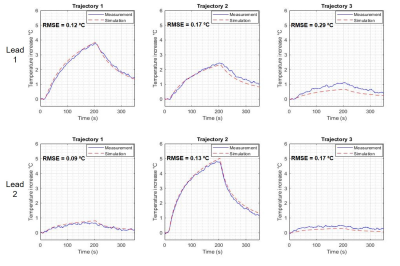

Using the transimpedance of 88 Ω, the Vc calculated are listed in Table 1 along with the maximum heating, ΔTmax and Is in each scenario. Figures 3 and 4 show the comparison between measured and simulated heating for each DBS configuration. We observed a good agreement (RMSE ≤ 0.20 °C) in 11 out of 14 configurations. The remaining 3 configurations achieved agreement RMSE ≤ 0.30 °C.Discussion

The temperature prediction workflow successfully predicted the heating of bilateral DBS in a human head phantom. Compared to our previous validations, the ROI of the incident B1+ measurement was reduced to account for the inhomogeneity in the B1 field in the phantom.The determined implant-friendly mode in Trajectory 2 successfully mitigated heating in both electrodes. Furthermore, the introduction of extra-cranial loops on the DBS electrodes also reduced the heating compared with straight contralateral and ipsilateral trajectories. This observation (although investigated in a limited manner in this work) is consistent with previous results7 presented by Golestanirad et.al.

This validation study was performed in a homogenous phantom, effects from variations of tissue EM and thermal properties, as well as perfusion, need to be considered when the workflow is utilized in-vivo.

Conclusion

The proposed temperature prediction workflow is able to accurately predict the heating in a realistic head-shaped phantom with bilateral DBS undergoing MRI.Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the following grant: NIBIB P41 EB027061, NINDS R01NS115180, and devices donated by Abbott Neuromodulation.References

- Boutet A, Chow CT, Narang K, Elias GJB, Neudorfer C, Germann J, Ranjan M, Loh A, Martin AJ, Kucharczyk W, Steele CJ, Hancu I, Rezai AR, Lozano AM. Improving Safety of MRI in Patients with Deep Brain Stimulation Devices. Radiology. 2020 Aug; 296(2):250-262. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020192291. Epub 2020 Jun 23. PMID: 32573388; PMCID: PMC7543718.

- Henderson JM, Tkach J, Phillips M, Baker K, Shellock FG, Rezai AR. Permanent neurological deficit related to magnetic resonance imaging in a patient with implanted deep brain stimulation electrodes for Parkinson's disease: case report. Neurosurgery 2005; 57:E1063.

- Shrivastava, D., Abosch, A., Hughes, J., Goerke, U., DelaBarre, L., Visaria, R., Harel, N., & Vaughan, J. T. (2012). Heating Induced near Deep Brain Stimulation Electrode Electrodes during Magnetic Resonance Imaging with a 3T Transceive Volume Head Coil. Physics in medicine and biology, 57(17), 5651. https://doi.org/10.1088/0031-9155/57/17/5651

- Sadeghi-Tarakameh, A, Zulkarnain, NIH, He, X, Atalar, E, Harel, N, Eryaman, Y. A workflow for predicting temperature increase at the electrical contacts of deep brain stimulation electrodes undergoing MRI. Magn Reson Med. 2022; 88: 2311- 2325. doi:10.1002/mrm.29375

- Eryaman Y, Kobayashi N, Moen S, Aman J, Grant A, Vaughan JT, Molnar G, Park MC, Vitek J, Adriany G, Ugurbil K, Harel N. A simple geometric analysis method for measuring and mitigating RF induced currents on Deep Brain Stimulation electrodes by multichannel transmission/reception. Neuroimage. 2019 Jan 1; 184:658-668. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.09.072. Epub 2018 Sep 28. PMID: 30273715; PMCID: PMC6814167.

- Bhusal, B., Nguyen, B.T., Sanpitak, P.P., Vu, J., Elahi, B., Rosenow, J., Nolt, M.J., Lopez-Rosado, R., Pilitsis, J., DiMarzio, M. and Golestanirad, L. (2021), Effect of Device Configuration and Patient's Body Composition on the RF Heating and Nonsusceptibility Artifact of Deep Brain Stimulation Implants During MRI at 1.5T and 3T. J Magn Reson Imaging, 53: 599-610. https://doi-org.ezp3.lib.umn.edu/10.1002/jmri.27346

- Golestanirad, L., Angelone, L.M.,

Iacono, M.I., Katnani, H., Wald, L.L. and Bonmassar, G. (2017), Local SAR

near deep brain stimulation (DBS) electrodes at 64 and 127 MHz: A

simulation study of the effect of extracranial loops. Magn. Reson. Med.,

78: 1558-1565. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrm.26535

Figures

Figure

1. Human head-shaped phantom consisting of a nested skull and an

outer tank. 2 contralateral DBS electrodes were fixed in the phantom and two

fluoroptic temperature probes were positioned 2-3 mm from the tip of the DBS

electrodes. This phantom allowed us to change the trajectory of the extra-cranial portion of the electrode while keeping the distal ends in the skull fixed.

Figure 2. DBS distal

end trajectories in the inner skull. The red lines indicate the

3D-GRE planes containing the Tx-null for current measurements. The planes are

orthogonal to the rotation angle of the DBS electrodes.

Table 1. Measured

results of maximum heating during TSE sequence, ΔTmax, induced current along

DBS electrodes, Is, and the calculated contact voltages, Vc,

for both DBS electrodes in each excitation and trajectory.

Figure 3. Comparison between the measured and simulated heating of bilateral DBS exposed to different excitations. Excitations 1-3 were performed with the same trajectory. Excitation 4 corresponds to an implant-friendly mode obtained by reducing the current induced along two electrodes simultaneously.

Figure

4. Comparison between the measured and simulated heating of bilateral DBS of

different trajectories exposed to circularly polarized excitation mode of the body coil.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.58530/2023/0606